2023-8-9 12:57 /

殖民性的电影时间

——论新海诚的《云之彼端,约定的地方》

原作者:加文·沃克(Gavin Walker)

文章原名:The Filmic Time of Coloniality: On Shinkai Makoto’s The Place Promised in Our Early Days

翻译:FISHERMAN

原文链接(Project MUSE)

新海诚的首部长篇剧场版动画《云之彼端,约定的地方》(雲のむこう、約束の場所)于2004年上映。这部动画巩固了新海诚作品“新生代动画流派”的地位:其风格独树一帜,既非沿革自宫崎骏老派的大预算电影风格,也不像上一代日本动画那样由制作委员会出品(以GAINAX社为代表)。新海诚是一位典型的数字时代的动画监督,他在2001年独立制作【译注1】的出道短片作品《星之声》(ほしのこえ)或许是后来被称为「世界系」(セカイ系)的这种新美学体制(aesthetic regime)的最集中体现。

《云之彼端,约定的地方》(后文简称《云》)是一部双重意义上的时代精神电影:一方面,《云》的成功、感性(sensibility)、制作方式(condition of production)和视觉风格(register)使之成为了一部代表了日本动画典型特征的鲜明转变【译注2】的作品;另一方面,《云》的叙事结构亦将其与近年来的“架空历史”电影热潮、以及该热潮所隐含的意指域(field of significations)的政治直接联系了起来。但更具体地说,作者认为《云》自身是另一种事物的载体——它是殖民性(coloniality)问题的表达装置,通过殖民性,我们不仅可以解读殖民体系的历史记忆和历史意义问题,而且还可以结合当代民族国家表面上的“后殖民”体系中正在发生的转变来解读殖民体系的认知论影响范围。《云》在它的视觉政治和叙事弧中作为透镜发挥着作用:透过它,(我们可以看到)殖民主义的时间性和历史的书写在对当下(present)的密集再编码过程中交织并重叠。

电影的叙事背景基于一段并非难以想象的架空历史:在二战后的数十年间,日本被美国和“联盟”共同占领,并于1973年分裂为联盟控制的北半部分和美国控制的南半部分。[1] 随后,日本南部由美国的专属占领区转变成了美日政府的“同盟”——它和联盟的国际性武装冲突迫在眉睫,而在影片的高潮部分,两国间爆发了战争。联盟控制着“虾夷”,即现实世界中的北海道,而美日同盟则统辖着津轻海峡以南的地区,也就是现实世界中除北海道以外的日本领土。从影片的视点看来,虾夷是一片神秘之地,而未被详尽描述的联盟则是一个谜一般的封闭社会。在《云》中支配着一切的,是一座巨塔:它从周围区域的平行宇宙中生成着物质。由联盟在虾夷南部边缘建造的这座巨塔高耸入云,并似乎能在整个日本南部被看见。虾夷巨塔,是电影叙事和影片镜面领域(specular field)的聚焦点。

《云》向观众介绍了三位(架空历史中的)现代青森县的中学生:互为好友的藤泽浩纪和白川拓也,以及他们的同学兼共同憧憬对象(object of desire)——泽渡佐由理。着迷于虾夷巨塔的两位少年在业余时间里建造着一架飞行器,他们希望乘着它飞跃津轻海峡,前往彼岸的巨塔。发现了这件事的佐由理成为了他们这个小团体的第三位成员。少男少女们向彼此承诺:在未来,一定要实现这个梦想。随着电影时间的推移,浩纪变成了一位抑郁的大学生,他在东京独自生活,并空想着他对佐由理的爱。拓也成为了青森军事学院的天才军事科学家,研究着虾夷巨塔的怪异影响、和它生成的平行宇宙。与此同时,佐由理陷入了昏迷。我们后来发现,她的状况和那座怪异的巨塔之间有着直接联系。最终,浩纪得知了佐由理的厄运;相信和巨塔的接触可以使佐由理苏醒的浩纪计划带着她飞往年少时那“约定的地方”,即虾夷巨塔。如今已参与到名为“UILTA解放阵线”的统一游击运动中的拓也则说服浩纪驾驶他们年少时建造的飞行器载着佐由理前往巨塔,并用一枚导弹摧毁现在被认为是联盟兵器的它。浩纪在日本南北开战前夕完成了他的使命:他使佐由理恢复了意识,并摧毁了虾夷巨塔。

自影片伊始,「分裂」(division)便成为了推动叙事展开的基本桥段,它们包括:故事情节自身时间的分裂,它被分为观众所感知的时间、和最初的叙事独白所感知的时间这两个部分【译注3】;日本的南北分裂,和因此分崩离析的诸多家庭;渐行渐远的三位主角和昔日亲密无间的三人小团体之间的割裂;城市和乡村、以及“官方”和“私人”空间的割裂;浩纪和佐由理两人在梦境中浪漫邂逅的时间和“世界时间”之间的分隔...藉由重复出现的“分裂”主题,《云》向我们展示了一系列互相关联的问题:它们对于把握殖民性问题以及当今民族国家的境况而言至关重要。电影自身可以被解读为一个“平行宇宙”,其中,帝国民族主义与族裔民族主义互相依赖和相辅相成的本质,在分离自现实的当下(disjunct present)中得到体现——而不是在回到过去的幻想中得以体现,或者体现为对未来的预测。新海诚的“后殖民”剧本丰富地描绘了殖民性的认知秩序机制的轮廓及其起源/历史,而作者则想烦请各位读者注意到这部剧本的强有力的潜能和预见性。那么,我们所说的“后殖民”究竟是什么意思呢?就此,酒井直树【译注4】做出了一番精辟的总结:

现在,“后殖民”这一术语被广泛用于表述“在殖民体系之后”,或“依照时间顺序,排列在殖民体系之后的事物”。然而,我们最好避免这两种用法,因为:“后殖民”中的“后”指的是“事后”(post factum),也就是说,一种“为时已晚”、无可救药(取り返しがつかない)或不可挽回的状态。从后殖民的角度看来,“身为殖民者”这一特征是日本人身份存在(identity of being Japanese)的必然状态,而非某种可以被偶然归因为身份建构产物的补充状态。殖民主义的历史被这种不可挽回性封装在日本人的身份存在当中,因此在本质上,“身为日本人”便包含了“曾经身为殖民者”的事实。正是这段不可挽回的历史构建了名为“日本人”的身份,所以,实际上这段殖民主义历史的現存(genzon)才是准确意义上的“后殖民”。[2]

就此而言,殖民地自身是一种根本意义上的回溯状态,而这种状态只有通过后殖民性(作为朝向过去的投影)才可能成立。殖民体系实际存在期间,殖民性本身尚未建成——它不能对自身表征为殖民地,而只能对自身表征为其他事物。因此,殖民地就像某种试验场或研发机关(R&D organ)一般,为自身的余波(aftermath,或指后殖民)服务着——若后殖的运行环境(condition)已然确立,则为(可能的)民族-国家的治理技术服务。所以,民族国家以及身为国民的(国族)归属位置/立场,是通过殖民性的建成(而不是通过时间顺序上对殖民性的超克)才得以实现的状态。由此可见,后殖民是一种“不连续性中的连续性”,是一个只有当殖民体系成为回溯性现实后才会作为原始层面的权力关系发挥作用的管理控制回路(circuit)。因此,殖民性是一部机器:它的零件在殖民地中得到装配,但矛盾的是,它只有在后殖民的当下才能作为一个整体的权力回路发挥作用。我们可以将这种殖民性的运作定义为一种普遍的“权力的殖民性”(power of coloniality),而它则“使我们能够在一个由信息和通讯、由一种不位于任何特定民族国家内部的全球殖民主义支配的世界中,理解时至今日仍在不断再现的殖民差异和它的历时密度(diachronic density)。”[3]

在这种情况下,我们有必要使自己置身于酒井教授所说的“殖民主义历史的现存”的决定性意义当中。新海诚通过南北“分断体制”[4]所描绘的日本国家分裂的动画影像不仅明确影射了日本语境下的战败史和同盟国军事占领历史,而且它还使我们注意到民族国家自身的普遍的分裂,或更广泛而言的,我们“身为国民”(being national)的分裂:殖民体系并不是当今民族国家过去的“反常状态”或“偏离正轨”,而是当今民族国家的基本内部构成要素——《云》重新反映,或回溯性地揭示了这一点。

《云》既不是对未来的幻想,也不是基于假想过去的回溯性预测(retrospective projection),而是平行于现实的当下;就此而言至关重要的,是在个人的直接存在(immediate existence)结构中审视(我们有必要如此)殖民主义的历史、殖民性现在的影响、以及“身为国民”在自身内部的作用——《云》在它的电影时间中向我们阐释了这一点。电影中,个体主观地把握着客观系统(世界),并因此生成了一种内在于(而不是外在于)自我意识的他者性(otherness)。正是这种内部/外部、私人/官方、或个人/世界的[分裂]重复表达了《云》的美学,而作者认为:我们可以在这种美学中,一睹当代殖民性的时间(time of coloniality)的情感驱动力。

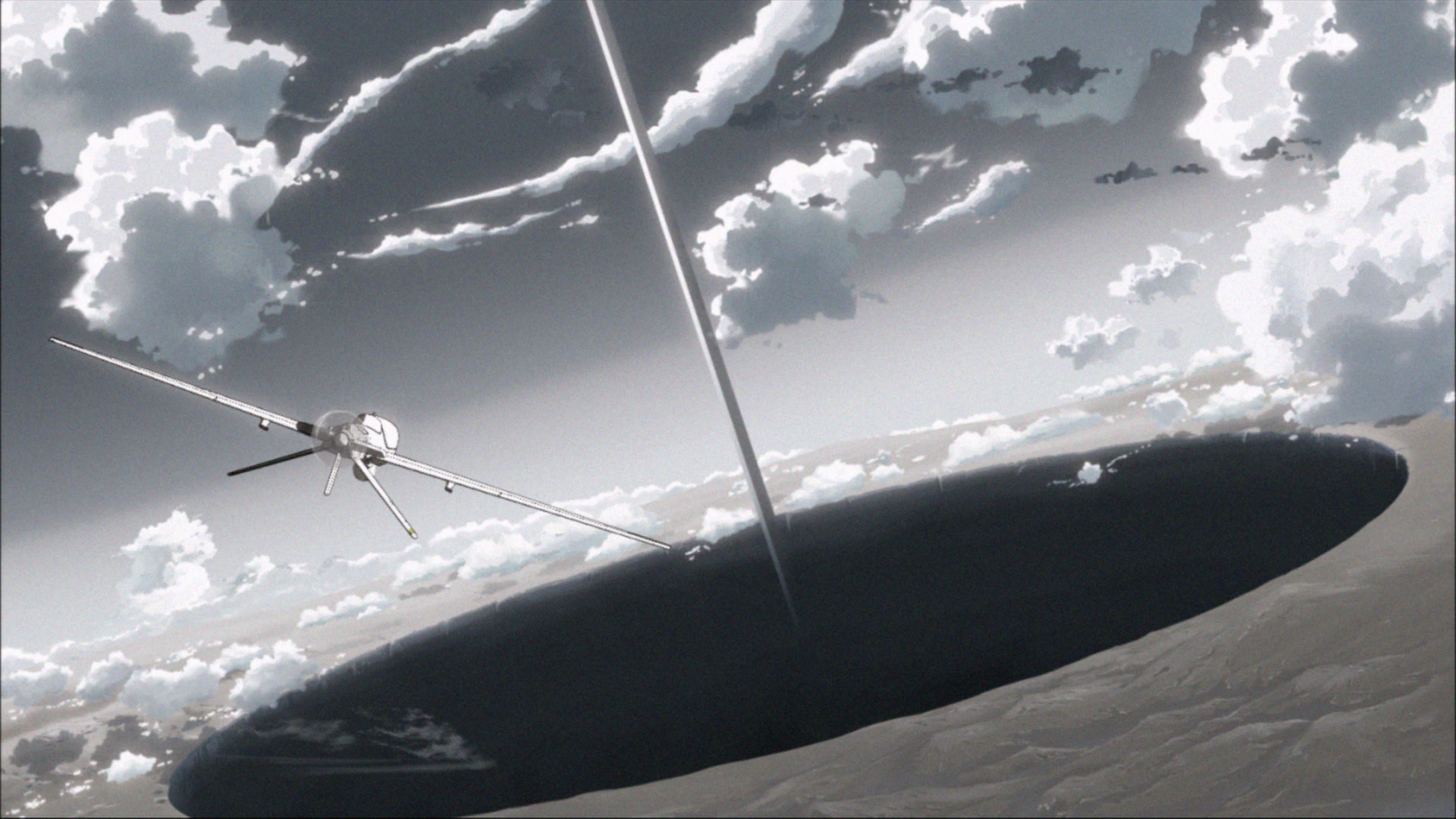

故事开始时,放学后的拓也和浩纪正在青森车站等候下一班电车。他们谈论着即将到来的暑假、和两人在一家为美军供货的弹药工厂的兼职工作。当少年们准备登上电车时,上摇的画框(“镜头”)向我们展示了虾夷巨塔令人震惊的规模:被落日染上红晕的它,在视觉上将背景中的天穹一分为二(见图1)。我们在这个镜头中看到:巨塔既是广袤无垠的自然背景之不可或缺的组成部分,又是电影镜面逻辑的秩序组织焦点(ordering focal point)。与之形成鲜明对比的是浩纪的身影和电车的轮廓,它们共享着观众的摄像机凝视(对象/方向):渺小的、植根于地面的、向上凝望的少年与电车,无一不在突出强调它们和巨塔的尺寸差异。当我们的视线上移至虾夷巨塔顶端时,藤泽浩纪离身(disembodied)的画外音向我们倾诉道:“那时,我们的心中憧憬着两件事。憧憬之一,是同年级的泽渡佐由理,而另一个...是耸立在隔着津轻海峡国境彼端的,巨大的塔。”【译注5】

图1. 虾夷巨塔在视觉上将背景中的天穹一分为二。所有截图均引自新海诚的首部长篇剧场版动画《云之彼端,约定的地方》(原文中的黑白截图由译者替换为彩色版本)

由此可见,佐由理代表了一切联系紧密、近在咫尺的亲密事物,而巨塔所象徵的则恰恰相反:它是遥不可及的、异国的、人造的、神秘的;在电影前期,这种被称为世界系(风格)的美学感性得到了明显的渲染。

“世界系”一词出现于零零年代初期,它被用于描述某种浮现自日本动画、漫画和电子游戏等亚文化艺术的共同美学(shared aesthetic),是一种意义模糊的笼统说法。尽管并没有对世界系确切构成要素的普遍公认定义,但它常被用来表示一种特定类型的、依赖着浪漫叙事(它扮演着世界-历史性/星际/国际冲突的前景[foreground])结构的美学风格。世界系风格中的重中之重,是苦乐参半的怀恋(bittersweet nostalgia);这种情感,往往由恋爱关系的线性时间性的断裂所调动——例如,闪回、闪前/预叙、和共存于同一电影情境中的多重时间线:它们是世界系的主要叙事装置。

世界系作品总是将爱情同战争、地球、国家等宏大事物并列叙述,而这种相提并论正是使世界系的怀恋得以运转的惯用手法:通过想象/幻想中的过去可能性/失却的希望在恋爱关系中的并置,处于冲突中的不同位置/立场(position)得到了彰显。在影像方面,世界系总是倾向于宏观审美化(macro-aestheticization):外剧情音乐(extradiegetic music)以及由悬殊的(人-物)比例构成的视觉美学,是世界系的形式化特征。亲密邻近的标志,是渺小、缓慢、轻柔、静寂、人物剪影、甜蜜的回忆、触摸/触感,和(这一切)消逝的瞬间,而“世界”和距离的特征,则是巨大(bigness)、快速、沉重、多元话语性(multivocality)、无止尽的差异化、宏大(immensity)、纪念碑性、世界-时间(与社会性的时间相反)、等等——在二者的并置中不断再现的,是唯美主义与凝视冥想(contemplation)的倾向、以及相互平行的个人与世界。风景和它与个人之间的关系,既是新海诚电影反复使用的意象,亦是一种反复呈现了并置的悬殊比例的视觉结构。

但是对于世界系而言,情感层面(以及社会层面的消解)同等重要:上文所述的个人与世界的关系,正是运作于情感层面之上。世界系作品中的世界并不只是“世界本身”,它同时也是“我的”世界。因此,《云》反复强调了作为“世界”的,个人生活中的封闭、狭小、内部的心理空间。好似“和某种唯我论眉来眼去”的这种心理倾向可以说是一种典型的后福特主义现象,而大部分“先进”工业化国家中的年轻一代都深受这种现象熏陶。一方面,就信息/通讯点阵网络(latticed network)、影像的共通性(commonality of image)和日常时间的同步化等方面而言,世界的边界正变得愈发松散;同时,世界的尺寸也在急剧缩小,而这则反映了商品单元的萎缩、以及商品单元不断升高的集中度。所以,世界既是宏大的,又是近在咫尺的,而自我的位置则在这种交叉所促成的感染错合(contamination)中变得更加“全球化/世界化”。

与此同时,访问“世界本身”的方式正逐渐被一系列全新、密集的技术所中介化;最重要的是:在很大程度上,早先我们赖以理解个人/世界概念的社会性正在被取代。例如,作者可以和越来越多的人建立起联系;纵使他们来自遥远的各地,并拥有海量的信息、观点和情感,作者也可以通过移动电话和计算机的二维屏幕等媒介与他们建立联系。因此我们可以认为,世界系美学的基本要素是“世界”的新发现——换言之,世界和它宏大的尺寸规模、以及它那压倒性的开放感,亦包含在当今客体的微观化所暗指的“狭小空间”当中。新海诚的处女作《星之声》的开场部分完美地例证了这一点:其中,覆盖在开场部分之上的,是女主角的画外音——美加子在手机上拨出电话号码,同时,她的声音向我们倾诉:“有一个词语,叫做‘世界’。直到中学时代为止,我一直模糊地认为,所有‘世界’,就是电波能够达到的地方。”【译注6】

然而新海诚电影,特别是《云》所展现的并不是某个作为远在个体意识之外的独立自主的场域被发现的所谓“世界”,而是一个被认为是和“自我”的形成息息相关且无所不在的结缔组织的“世界”。我们可以在世界系作品中发现一种纯粹的唯我/孤独/可怕的社会性,在这种社会性中,“世界”意味着个人所必须逃离的一切。不过,我们也可以在《云》和其他世界系作品中看到某种“一般智力”(general intellect),也就是参与至世界及其历史的重复型构(figuration)过程中的日益社会化的知识——作者认为,这要更具启发性。(见图2)

图2. “...可那时,夜里电车的气味、对朋友的信赖、还有空气中回荡的佐由理的气息,让我感到这就是世界的全部(世界のすべて)。”

当浩纪、拓也和佐由理走回青森车站时,浩纪讲述了他们自从少年时代以来的变化。在电车驶离车站时,凝望着车窗外的浩纪说道:“尽管世界和历史即将发生巨变,可是那个时侯,漂浮在车厢里的夜的气息、朋友间的信赖、还有空气中回荡的佐由理的气息,让我感到这就是世界的全部(世界のすべて)。”这一幕中,纪念碑性(所谓“世界”和“历史”本身)和微型化(即作为另一个世界的,你我之间的关系)的并置再次向我们展示:很大程度上,此处的“世界”只不过是一系列的意指,它既是绝对外在事物的载体,也是一系列内部情感判断的载体——存在这样一种普通逻辑(common logic),它沿着同样被称为“世界”的意义链或认同链(chain of meaning or identification),通过这种内部情感判断,将这二者连接起来。

《云》无时无刻不在将“世界”作为某个意义存疑且不稳定的客体进行调动:它是作为某种一元美学(unifying aesthetic)被创造出来的,而胜过一切的是,我们只需要通过这一点便能识别该客体——某种意义上来说,影片建立在作为物质-符号域[5]的世界的密度这一概念基础之上,并展示了这一概念。因此,世界系不一定意味着自历史记忆的责任和负担这一端反动地回退(至意识形态舒适区),在其他解读方式中,它亦拥有能够直面历史记忆之责任负担、并且正在发挥作用的相反潜能。正因为它打破了“世界”的密度这一概念(后者倾向于将“世界”作为一系列可塑性情感风格的总称),所以,世界系才将世界和历史作为型构物加以承认和想象;也就是说,世界系表明:一个世界及其历史的形成,便是这个世界及其历史本身。所以在电影中,书写、改写/再书写(rewriting)、覆写或“编码”的问题才是关键所在(情理之中)。《云》不仅在自身的叙事和与之相关联的“世界”中,而且还在它的视觉逻辑中,将一系列和我们的当代时刻(moment)相关的决定性问题摆上台面;然而,我们将会在文章末尾部分的分析中看到:电影自身却是通过逃避它本身所阐明的问题从而使问题“得以化解”的。

《云》既不是对未来的预测,也不是对过去的重新想象,这一点作者在文章开头部分便已提及——恰恰相反,它本身便是一种平行于现实的当下、一种当代性(contemporaneity)的“混合”,而这则和《云》的剧情叙事相一致。电影本身就是一个“世界”,也正是这一点使之成为了日本动画领域的新型产品的突出代表——作为一部作品而言,《云》的传统(叙事)轮廓(作为一则“故事”、或一段“情节”)远不如它的“世界”重要。某种程度上,这便是(大塚英志和)东浩纪等学者所说的“动漫现实主义”(まんが·アニメ的リアリズム):《云》是一部建立在“世界”基础之上的作品,但我们只能将这个“世界”作为新海诚脑中的型构物予以发现;这是一种新型的现实主义,而这种主义的“现实”本身便是其自身的“世界”的反馈回路。[6] 不过,这一症候(problematic)不仅值得我们从动画制作的形式条件(formal condition)角度进行分析;作为影片内部逻辑的一部分、以及某种可以说是被《云》的叙事本身所“理论化”的事物的它同样值得我们去解读。

随着电影时间向前推移,拓也开始在专职负责侦察/调查虾夷巨塔的同盟绝密研究部门担任研究员,而《云》则向我们讲述了越来越多有关巨塔力量的(背景)信息。原来,巨塔是一个与梦境密切相关的装置。当拓也和他的同事(同时也是新的爱慕对象)笠原真希重返他和浩纪曾经兼职过的弹药工厂时,真希向大家解释道:“就像人夜里会做梦一样,这个宇宙也在做梦;事物的发展有多种多样的可能性,而世界把它们藏在梦里,对于这种现象,我们称之为‘平行世界’或‘分歧宇宙’。”就在这一幕之前,我们了解到:一位名为艾克森·赀吉诺谒(エクスン·ツキノエ)的知名联盟科学家证明了“平行世界”的存在;他是巨塔的设计师和巨塔建筑工程的总监。在巨塔周围,有一片充斥着“截然不同的物质”的空间,它自身由“别的宇宙”所构成,而夹在《云》所处的世界和巨塔周边的区域当中的空间则此起彼伏、连续不断地“与这些平行世界进行着空间置换”。也就是说:某种程度上,巨塔是它周围所有人的梦境在空间层面上的具现(concretization)。但我们并不能简单地认为是巨塔生成了这些“平行世界”;恰恰相反,这些世界是所有生物的大脑模式的内部特征——正因此,拓也隶属的研究单位才被称为“脑科学团队”。出现在脑科学实验室的美国国家安全局特工直观地证实了这项研究的重要性——这项技术的潜在力量来自它对未来历史结果的预测功能。然而,研究人员并不是通过考察线性的编年性时间当中的可能结果并计算它们的可能性,从而把握这些未来结果的。相反,《云》告诉我们:所谓的“未来”,是通过在这些“平行世界”中查看某一个实际未来(an actual future)的结果,从而被预测,或者更准确地说,被识别/确定的。换而言之,把握过去、亦或理解未来的能力,是通过另一种分离自现实的时间性与现实之间的概念重叠而产生的,以至于在某种程度上,《云》中不存在其他时间,除了当下以外:这是一种“永恒的现在”,它通过自身和其他平行的当下(时刻)的交叠,从而得到伸展、延长和收缩;同时,这也是一种从某个当下前往另一个当下、并从后者所在折回前者所在的,无休止的振荡。

自从三人“约定”前往巨塔之后,佐由理便陷入了昏迷状态,为时已有三年之久。然而,浩纪和佐由理彼此梦见了对方。他们平行的内心世界互相重叠——当浩纪在他的梦境中邂逅佐由理时(也就是说,他在“他自己”内部遇见“她”时),他认为,这种体验要“比现实更加真实”(現実よりも、現実らしく),换言之,“比当下更像当下”(more present than the present)。当佐由理在她的“私人”内部空间(表面如此)中看到浩纪后,她的梦境便发生了巨变,此时,巨塔开始将其内含的平行现实覆写至周围的现存物质世界之上。慌乱的“脑科学团队”正竭尽全力阻止“真实”的物质世界被这个不断扩大的“平行世界”吞噬,而随着“覆写”物质的环状范围不断扩大(见图3),主任研究员富泽常夫自我叩问道:“[他们]这是要…置换[改写]整个世界吗(世界を書き換えるつもりなのか)?”

图3. 巨塔开始将其内含的平行现实覆写至周围的现存物质世界之上。

巨塔正在“改写”世界和历史,同时,它也在结合其他的平行当下——《云》的叙事所在的当下与它们同时存在/发生——内部无尽的可能性,对电影所在的这个当下的现实性(facticity)进行再编码,从而颠覆这种现实性本身。所以,就《云》的时间性而言,我们可以看到存在于/发生在电影叙事内部层面并为正在观影的观众服务的、和前文一样的再编码过程。由此看来,我们可以这样理解影片:它自身描绘了某种动画电影逻辑(即世界系)的发展,而后者对于计算机化、数字化、非物质化等进程所隐含的情感结构而言至关重要。也就是说,《云》这部动画(特别是它的表现功能)体现了保罗·维利里奥所说的广延时间(extensive time)与密集时间(intensive time)之间的过渡。

逐渐在数字化进程和计算机化与自动化的瞬时性(instaneity)中被取代的,是广延时间的逻辑:它“致力于加强无限的伟大时间(great time)的整体性”,并遵照“过去、现在和未来”的时间顺序进行表述。广延时间所在之处逐渐出现了一种“密集时间”,它不再跨时态进行组织部署,而是在影像的“实时”(real time)和“延时”(delayed time)中进行结集(marshal)。[7] 在《云》中,正是作为“实时”及其置换的中介的巨塔阐释了这一点。发生在巨塔周围的置换,既不是过去向未来、也不是未来向过去的变换,而是电影叙事和其他当下(包括观众所在的那个)的“实时”的加强与压缩。

新海诚在《云》中运用的动画技法广受赞誉,而其中一项便是:(在背景绘制过程中)将照片作为参照点使用。本质上,电影中的背景/场景是用一种新型的数字覆写或数字重构的方式,在青森县的实拍影像“之上”绘制而成的。也就是说,在这种视觉性中运作的想象过程,并非源于对“新”世界的想象(例如早先的“边疆开拓(extensive)”型科幻当中的想象),而是源自这种视觉性在世界系风格中的屈折变化(inflection)——换言之,作为现实的混合或现实的并置的科学幻想——当中所蕴含的新型感性。正如巨塔使“世界”的空间得到改写或再编码那样,新海诚通过对青森和东京的视觉风格的再编码,从而改写了“日本”的空间。对此,东浩纪评论道:“当我第一次观看[新海诚的]《星之声》时,我就想,这部作品和迄今为止的日本动画是完全不同的。它不是运动的影像(moving image);相反,它更像是一组恰好在运动的静态影像。”[8] 也就是说,《云》(以及《星之声》)当中运行着一种吊诡的双重视觉指涉性系统——静态影像和观众的“实时”重叠、并与观众对空间性的感觉(sense of spatiality)交叠在一起,但当静态影像开始运动时,它并没有在观众的“实时”之内运动,而是以一种置换性的、平行的轨迹(也就是在电影时间中)进行运动,从而在视觉上为观众“从理论上说明”了当下所包含的多种发展方向的内在可能性。

动画影像的“平行世界”对观众的“实时”与空间进行了图层叠印(graphic superimposition)、描摹和复制,藉此,《云》自身成为了“用密集时间/密集空间取代广延时间(/空间)”的完美象徵,进而直接强调了“历史和记忆是持续建构的产物’”这一点。对历史轮廓的再书写或再绘制,是一种重新勾勒/重新绘制世界本身的空间边界的表达行为,也是一种位于某个不稳定且被部分决定的当下内部的、无休止的即兴型构(过程),而这种当下则在当代认知资本主义(cognitive capitalism)中变得愈来愈明显可见。

《云》阐述了殖民性的“当下”性质、持续创造着“现在”(here)的时间性、以及,情感与姿态(gesture)等等(表现)的,新兴且直接的(意义)生产能力。通过将“我们的”现实/当下的概念结构置换和错位(dislocating)至另一种当下(在这种当下中,相同的物质被不同地组织起来),电影自身成为了“地缘政治的后殖民情境”的一帧影像,而这种情境则被当作“下述思想的某种范式,即认为历史本身是一种型构(过程/产物),而它以‘真实的物块’(chunks of the real)构建了某种事物。”[9] 也就是说,《云》作为一件作品的力量并不在于它(对战争/民族/历史等物的)规范刻板的反思能力,而在于它以展演的方式对我们所继承的历史组织形式提出了质疑。

准备履行约定和佐由理一起飞往巨塔的浩纪,登上了开往家乡青森县的列车。当我们看到浩纪在火车上阅读宫泽贤治的《春与修罗》(春と修羅)时,我们同时在画外音中听到冈部对UILTA解放阵线的同志们所作的说明:“如你所知,那座塔很明显是武器。二十五年来,那座塔已化作熟悉的风景,以及种种事物的象徵:国家、战争与民族,亦或是绝望与憧憬...每一代人都有自己的接受方式,但是,世人都认为它遥不可及,都认为它永恒不变,唯有这一点是相同的;倘若都如此作想,这个世界就会一成不变。”列车车窗上映出了巨塔的身影,而我们则在自己的观影银幕上再次看到了电影中的当下的双重效果——阅读着“我们”的现代性语境中的经典文本的少年(底层图层),坐在一列可以被认为是属于“我们”的历史-技术革新产物的交通工具上(中层图层),而叠印在这一切之上的则是巨塔(顶层图层),换言之,“他的”当下的象徵秩序机制(见图4)。如此看来,新海诚的这部影片可以被解读成一种服务于我们的复制和错位装置,以及,观看一系列静态影像、照片,和我们的当下——正在无休止地消失和涌现的,位于自身内部的当下——内部的可能性的运行动作(movements of the operation of contingency)的方法。

图4. 《云》中的当下的双重效果:一位阅读着“我们”的现代性(文本)的少年(底层图层),坐在一列属于“我们”的历史-技术革新产物的交通工具上(中层图层),而叠印在这一切之上的则是巨塔(顶层图层),换言之,“他的”当下的象徵秩序机制。

由此看来,《云》结构性地表达了当下的殖民性以及它在“我”体内不可逆转的定位,但在叙事层面上,它却在结局部分揭示:自己是对历史的逃避,而逃避的前提,则是对直面情境性(situatedness)或位置性(positionality)的不甘与拒绝。从殖民主义历史的事实中使“自我”得到扭转/修复/救赎,是不可能的——因此,需要指出的是:《云》察觉到,作为观众的“我”在将“我的”当下认定为殖民性的时间的同时,也默认了这种不可能性。所以在电影中,通过当下的分裂,“时间的线性流动”这个总问题(尤其是殖民体系“从开始、建成、再到崩溃”的传统线性叙事)得到了置换。殖民性存在于我们的时间和我们当中——《云》的形式本身便是建立在这种理解之上,所以,它绝不能被指责说是抹煞了殖民主义的历史。但是,电影并没有使这一相互关联的问题网络得到自然而然的解决;相反,可以说:《云》虽然是一种审视当下(immediate moment)的殖民性的机制,但它却致力于抹煞当下和逃避面对自身内部的当下。令人不安的,从来不是对殖民暴力时刻的回溯性-线性凝视,而是使我们止步不前的,“我们”的实际现存。“我”的“自我”正是后殖民的场域(就其不可逆转性而言),而这种“自我”本身,正是一种总是已经被卷入后殖民的存在。

巨塔总是能被看见,但在根本上却是触不可及的——在电影开头部分,当浩纪描述虾夷和巨塔时,他认为巨塔生成幻想(即平行世界)的镜面能力正是源于这一事实。巨塔,是一处“‘眼见着好象伸手就能触到的距离,但却到达不到的那个地方’...我们不管怎么样也要亲眼去看看。”就这样,三人计划完成某种不可能的事情,即遇见并征服“真实”(the Real)。冈部的观点与此如出一辙,他认为,只要作为战争、民族-国家、种族等事物的象徵的巨塔仍然可望而不可及,这些事物本身便无法得到改变。但在《云》中,情况恰恰相反:浩纪和佐由理抵达了巨塔,佐由理恢复了清醒,并且,他们的确用一枚导弹摧毁了巨塔。所以,在电影高潮部分,“战争”、“种族”、“民族-国家”等事物并没有得到正视或被重新建构——正是因为巨塔的覆灭,才使得这些束缚被彻底摧毁。就此而言,巨塔不只是欲望和梦想等等事物的外在化具现,它在电影中还是“我”(即殖民者)内部的某种事物,在其中,“责任”、“罪责”等事物的意指链条超越并在某种意义上控制了“我”,而“我”则迫切地企望摆脱这一切。所以...巨塔在一抹耀眼的橘红色光晕中爆炸(见图5),此时,浩纪和佐由理坐在他们年少时想要建造的飞行器中,漂浮于苍穹之上,接着,浩纪在画外音中说——这意味着,他并不是对佐由理,而是对观众说:“即使这个世界上没有了约定要去的地方,但是...我们的生活将从现在开始。”【译注7】

图5. 巨塔在一抹耀眼的橘红色光晕中爆炸,而浩纪和佐由理则坐在他们年少时想要建造的飞行器中,漂浮于苍穹之上:“即使这个世界上没有了约定要去的地方,但是...我们的生活将从现在开始。”

这便是《云》真正的梦想——“我”的内部存在着一种可被察觉的内核,它象徵着身为殖民者或压迫者的位置/立场,并且可以被外在化,进而被摧毁,这样一来,人们便可以重新来过,免于罪责与耻辱。所以,与其说摧毁巨塔是创造新世界的乌托邦式行为,不如说它是某种欲望的集中体现,即,想要摆脱自身无可救药的位置性,以及,想要摆脱询问“我的直接存在的‘事实’是建立在什么基础之上?”的必要性。《云》直面着最基本的“责任”问题;它面对着这一事实:“我”的身份,已然将身为殖民者的不可逆转的时间包含在内。而面对这一事实,《云》本质上以自己的形式叙述了自身“对(平行)宇宙的幻想”——幻想能够重新来过,并找到一个新的启程时刻,在那里,既没有“场域 / (约定的)地方”,也没有“位置”本身,而是有着一种无尽的、不受束缚的主体性,而它只取决于个体的自我定位。因此,《云》中这种令人难以置信的对位置性的畏惧可以向我们充分展示当下的“权力的殖民性”的作用,更不用说倚赖着它的当代资本主义的运作了。

可以说在电影高潮部分,直接和浩纪与佐由理的重逢并置叙述的是:摧毁巨塔(它是阻止国家统一的首要制约因素,也是象徵着边界与分裂的占位符)使日本南北实现了统一。但问题是,在两人重逢/国家统一之际,佐由理意识到:她失去了记忆;在没有历史记忆网格介入的情况下,她的精神生活将会沦为(纯粹的)直接经验(immediate experience),因此,她对浩纪的爱也会随着巨塔的覆灭而烟消云散。在世界系美学中,这种决定性的终结姿态——双重统一,亦或说,建立在“失散的年轻恋人的团聚”基础之上的国家统一,尽管是以牺牲过去(的记忆)为代价——似乎应当是苦乐参半的,但事实上却恰恰相反。失忆,才是究极的胜利;它既是(身份)可逆性和逃避(责任)的幻想,也是融入某种新的整体论(其中,历史记忆和创伤体验被排除在外)的幻想。

《云之彼端,约定的地方》回避了自身的可能性,因为它承认:民族共同体的本质——即,一种由民族(共同体)对持续再生产的需求所催生的型构空间——只是部分确定的。《云》并没有直面“我”和“我们”那无可救药的位置,而是致力于寻找一种彻底摆脱当下,也就是说,彻底摆脱自身的方法。然而,仅仅用反驳或“超克”的方式来对抗压迫史所带来的悲痛,是不可能的——自己与种族主义和殖民主义的历史等等事物“划清界限”,以使“我”能够发现一处没有污点的崭新位置,从而卸下身为自己(being myself)的负担,是绝无可能的:“唯一的选择,是在它(自己)所确定的可怕的感染错合之间做出选择。即使所有形式的共谋(complicity)并非等同,它们也是不可还原的。”[10] 在《云》中,触不可及的地方并不是剧情上的日本南北分裂(换言之,象徵着这一状况的巨塔),而是使“我”得以成为“我”的场域内部的分裂,而逃离这一场域是不可能的——只有当我们置身于这个“我”的形成过程所包含的(与殖民性的)共谋和(自身身份的)不可逆转性当中时,才可以出现一种能够把握并回应当代“权力的殖民性”的新型政治与新型社会性。

致谢

在修改论文以供发表时,作者想对托马斯·拉马尔给出的意见、建议以及他对本文精辟的批判性阅读表示感谢。与酒井直树、克里斯托弗·安(Christopher Ahn)和星野統明(Noriaki Hoshino)的讨论也让作者受益匪浅。同时,作者想要感谢《Mechademia》期刊的审稿人。所有英文以外语言的译文均由作者本人翻译,除非另有说明。

译注

1. 《星之声》于2002年2月2日上映。

2. 或指新海诚的一系列创新,例如背景写实、光影/色彩运用、世界系的作品主题,等等。

3. 原文为“the division of time into the time of the audience and initial narrative voice-over from the time of the storyline proper”,亦可译为“当最初的叙事独白响起时,分裂成观众的时间和故事情节本身的时间的‘时间’”,供读者参考。

4. 参见教授在康奈尔大学的简介页面:https://asianstudies.cornell.edu/naoki-sakai

5. 译文中,《云之彼端,约定的地方》的台词翻译参照自曙光社、POPGO FREEWIND、拨雪寻春字幕组、以及诸神字幕组的翻译版本。

6. 翻译引自诸神字幕组《星之声》字幕版本。

7. 作者的听译为“We've lost our promised place in this world, but now our lives can begin.”粗体部分为译者所加,旨在强调作者(可能的)分析解读思路。

附录

1. 值得指出的是,在日本战败并被盟军占领之际,美苏分治日本是一种确切的可能结果,而它将导致苏联吞并萨哈林岛(以及北海道等日本北方领土)。这并没有发生,不过,我们可以在分裂的朝鲜半岛的存在中,不断看到这种美苏分治的“实际情况”。

2. 酒井直树:《日本/影像/美国:共感的共同体与帝国民族主义》(日本/映像/米国―共感の共同体と帝国的国民主義),东京:青土社,2007年,页294-295;粗体部分为作者所加。这段表述并不只适用于文本中的案例,即作为假想的统一体(putative unity)的“日本”,它同时也是民族-国家归属形式的普遍状态——这是不言而喻的。

3. 沃尔特·米格诺罗(Walter Mignolo):<资本主义与知识的地缘政治>(Capitalismo y geopolitica del conocimiento),《殖民的现代性:其他的过去,当下的历史》(Modernidades coloniales: otros pasados, historias presentes),沙鲁巴·杜贝(Saurabh Dube)、伊希塔·班纳吉-杜贝(Ishita Banerjee Dube)、沃尔特·米格诺罗编,墨西哥城:墨西哥学院出版社(El Colegio de Mexico),2004年,页248。“权力的殖民性”这一术语出自阿尼巴尔·基哈诺(Anibal Quijano)的理论著作.

4. “分断体制”这一概念由白乐晴(백낙청)于上世纪七十年代提出,它被用于描述朝鲜、韩国与美国政府在朝鲜半岛的分裂所生成的影响范围之上的相互依赖体制;换言之,白乐晴在指出“分断”本身的暴力的同时还指出:“分断”被固化成了一个不断自我复制的“体制”。他就这一议题撰写了许多论文,参见白乐晴:<哈贝马斯谈德国与朝鲜的国家统一>(Habermas on National Unification in Germany and Korea),《新左翼评论》,第219卷(1996年9月/10月),页14-22(英译);白乐晴:<朝鲜半岛内部的殖民性,与韩国超克现代性的计划>(Coloniality in Korea and a South Korean Project for Overcoming Modernity),《Interventions》,第2卷、第1期(2000年),页73-86(英译).

5. 这一短语引用自唐娜·哈拉维(Donna Haraway);参见唐娜·哈拉维:《似叶》(How Like a Leaf),伦敦:劳特利奇出版社,2000年,页107;关于这一概念,另请参见唐娜·哈拉维:<处境知识:女性主义中的科学问题与局部视角的特权>(Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective),《猿猴、赛伯格和女人:重新发明自然》,伦敦:劳特利奇出版社,1991年,页183-201.

6. 参见新海诚监督、批评家东浩纪与漫画作者西岛大介的访谈:《从世界,到更遥远的地方》(セカイから、もっと遠くへ),原载于《波状言论 第16号(9月B号)》,2004年9月;访谈的重印版,参见东浩纪等作者:《内容的思想》(コンテンツの思想),东京:青土社,2007年,页34-35;东浩纪对这个问题的进一步讨论,另请参见《游戏性写实主义的诞生:动物化的后现代2》(ゲーム的リアリズムの誕生:動物化するポストモダン2),东京:讲谈社,2007年.

7. 保罗·维利里奥:《视觉机器》,朱莉·罗丝(Julie Rose)英译,伦敦:英国电影学会/布卢明顿:印第安纳大学出版社,1994年,页66-72.

8. 参见新海诚、东浩纪、西岛大介,《从世界,到更遥远的地方》,页23.

9. 佳亚特里·斯皮瓦克:《后殖民理性批判:正在消失的的当下历史》,麻萨诸塞州剑桥市:哈佛大学出版社,1999年,页62-63.

10. 雅克·德里达:《论精神:海德格尔与问题》,杰弗里·班宁顿(Geoffrey Bennington)、瑞秋·鲍比(Rachel Bowlby)英译,芝加哥:芝加哥大学出版社,1991年,页40.

In 2004, Shinkai Makoto's major film-length feature, The Place Promised in Our Early Days (Kumo no muko, yakusoku no basho) was released, solidifying the position of his work as that of a decidedly new generation, one stemming neither from the older big-budget cinematic style of Miyazaki nor the previous generation's anime studio system, symbolized by GAINAX. Shinkai debuted as a quintessentially digital-age auteur with his entirely self-created 2001 short film Voices of a Distant Star (Hoshi no koe), perhaps the most concentrated expression of this new aesthetic regime, which came to be known as “sekai-kei” (literally, “world-style”).

The Place Promised in Our Early Days (hereafter PPED) is in a doubled sense a Zeitgeist film: on the one hand, its success, its sensibility, its conditions of production, and its visual register make it a production representative of a distinctive shift in the archetypal anime feature; on the other hand, its narrative structure places it in direct linkage to the recent boom of “alternative history” films and the politics of the field of significations implicit to this boom. But more specifically, I argue that PPED is itself a vehicle for something else, an expressive device for the question of coloniality, one in which we can read the problem not only of the historical memory and meaning of the colonial system but also its field of epistemological effects in relation to the contemporary shifts occurring in the ostensibly “postcolonial” system of nation-states today. In its visual politics as much as its narrative arc, PPED is a lens through which the temporality of colonialism and the writing of history intertwine and overlap in a dense recoding of the present.

The backdrop to the narrative of the film proceeds from an alternative, but not unthinkable, history: in the decades following World War II, Japan is jointly occupied and, in 1973, divided into northern and southern portions: in the north by the “Union,” and in the south, by the United States. [1] Subsequently, the south shifts from an exclusively U.S.-occupied territory to an “Alliance” of the American and Japanese governments — conflict with the Union is impending, and at the climax of PPED, war breaks out between them. The Union controls Ezo, what would be contemporary Hokkaido, while the Alliance governs the rest of modern-day Japan, south of the Tsugaru Strait. From the film's vantage point, Ezo is a site of mystery, and the Union is a closed and enigmatic society left largely undepicted. Dominating all is the immense Tower, which generates matter from parallel universes in the area surrounding it. Built by the Union on the southern edge of Ezo, it stretches far into the sky and is seemingly visible throughout southern Japan. It serves as a focal point both of the narrative and of the specular field of the film.

We are introduced to three middle-school students in modern-day Aomori: friends Fujisawa Hiroki and Shirakawa Takuya, as well as their classmate and mutual object of desire Sawatari Sayuri. The two boys, who are fascinated by the Tower in Ezo, are constructing an airplane in their spare time, with which they hope to fly across the Tsugaru Strait toward the Tower. Sayuri, who discovers this, becomes a third member of their group, and they promise each other that in the future they will achieve this dream. As the narrative shifts to years later, Hiroki is a depressed student in Tokyo, living alone and daydreaming of his love for Sayuri, while Takuya is a precocious military scientist at the Aomori Army College, studying the bizarre effects of the Tower in Ezo and the parallel universes it generates. Sayuri, meanwhile, has slipped into a coma –– it turns out that her condition is directly related to the strange Tower. Eventually, Hiroki learns of Sayuri's fate, and plans to fly her to the Tower, their “promised place” from childhood, believing that contact with the Tower will wake her up. Takuya, now also involved in the reunification guerrilla movement known as the Uilta Liberation Front, persuades Hiroki to fly their childhood plane, carrying Sayuri, to the Tower, now understood to be a Union weapon, and destroy it with a single missile. On the eve of war between North and South, Hiroki accomplishes his mission, reviving Sayuri, and destroying the Tower in Ezo.

From the outset of the film, division is the essential trope through which the narrative proceeds — the division of time into the time of the audience and initial narrative voice-over from the time of the storyline proper, the division of the country into north and south, the division of families as a result of this national division, the division between the three protagonists of the story from the holistic group of their childhood, the division between city and countryside, between "official" space and "private" space, between the time of the romantic encounter and the time of the world, and so forth. Through the recurrent theme of division, PPED shows us a series of interconnected problematics essential to grasping the question of coloniality and the position of the nation-state today. The film can be read as itself a "parallel universe," in which the mutually reliant and reinforcing nature of imperial and ethnic nationalisms is incarnated in a disjunct present, rather than in a fantasy of return to the past or as a projection of the future. I would like to draw attention to the strong potentiality and prescience of Shinkai's "postcolonial" scenario, which richly portrays the contours of the epistemic ordering mechanisms of coloniality and their provenance. Naoki Sakai has delivered an essential summation of the question of what we mean by the postcolonial:

It would be better to avoid the sense in which the term "postcolonial" is broadly used today to mean "after the colonial system" or "what follows the colonial system in chronological order." This "post-" is "post factum," that is, "post-" in the sense of a situation that is "too late," irreparable (torikaeshi ga tsukanai), or irredeemable. Thought from the postcolonial viewpoint, the characteristic of being the colonizer is not an accidentally attributable supplemental situation to the identity of being Japanese, but rather its essential situation. The history of colonialism is sealed into the identity of being Japanese by means of this irreparability, and thus having been the colonizer is essentially included in being Japanese. It is the fact of this irreparable history that constructs the identity called "Japanese," and thus in fact it is the present existence (genzon) of this history of colonialism that is precisely the postcolonial. [2]

In this sense, the colony itself is a fundamentally retrospective condition, which is possible only through postcoloniality as a projection back toward the past. During the actual existence of the colonial system, coloniality itself is not established — it cannot be represented to itself as a colony but only as something else. The colony is consequently something like a testing ground or a research-and-development organ for its own aftermath, when its conditions have been established, for the technologies of government of the nation-state. Thus, the nation-state, and the position of belonging to it as a national citizen, are conditions enabled not through the chronological overcoming of coloniality but rather through its establishment. It is in this sense that the postcolonial is a type of "continuity in discontinuity," a circuit of regulation and control that only comes to function as the primary level of power relations after the colonial system has become a retrospective reality. Thus, coloniality is a machine whose parts are assembled in the colony, but which comes to function as a unitary circuit only, paradoxically, in the postcolonial present. We can identify this functioning as a kind of general "coloniality of power," which "allows us to understand the diachronic density and the constant rearticulation of colonial difference even today, in a world governed by information and communication, and by a global colonialism not located in any particular nation-state.” [3]

In such a situation, it is necessary to hold ourselves immanent to the decisive meaning of what Sakai has called the "present existence of the history of colonialism." Shinkai's image of the split of Japan through a NorthSouth “division system” [4] is not only a clear allusion to the history of defeat and occupation in the Japanese context but also something that alerts us to a general split of the nation-state itself, or more broadly, a split of our "being national": it reimages or retrospectively reveals how the colonial system was not an aberration or deviation but rather is an essential and internal element of the nation-state at present.

In the time of the film, in the fact that it is neither a fantasy of the future nor the retrospective projection of an imagined past but rather a parallel present, PPED explicates to us something crucial in this respect: it is necessary to examine the history of colonialism, the effects of coloniality today, and the role of "being national" in oneself, in the structure of the single person's immediate existence. The objective system is grasped by the individual subjectively, producing an otherness not external to the sense of self but rather internal to it. It is this division of internal/external, private/official, or individual/world which recurrently expresses the aesthetic of the film, and in which, I argue, we can see the affective drive of the contemporary time of coloniality.

At the beginning of the story, Takuya and Hiroki wait at their local train station after school, chatting about their upcoming summer vacation, and their part-time job at a munition factory supplying the U.S. military. As they prepare to board the train, the frame pans upward, exposing the incredible size of the Tower in Ezo, visually bifurcating the backdrop of the sky, (Figure 1) colored red by the setting sun. In this shot, we see the Tower as an integral part of the natural expanse, an ordering focal point of the film's specular logic. In marked contrast, the figure of Hiroki and the lines of the train share our camera-gaze: small, rooted to the ground, and gazing upward to emphasize the differentiation of scale. As our view pans toward the top of the Tower, Hiroki's disembodied voice-over tells us, "We admired two things — one was our classmate Sawatari Sayuri, and the other was the Tower."

Figure 1. The Tower in Ezo visually bifurcates the backdrop of the sky. From Shinkai Makoto's major film-length feature The Place Promised in Our Early Days (2004, Kumo no muko, yakusoku no basho).

In the sense that Sayuri represents everything close, nearby, and intimate, the Tower symbolizes precisely the inverse: distance, the foreign, the artificial and mysterious. In this early moment of PPED, the aesthetic sensibility of what has come to be called the sekai-kei style is visibly rendered.

"Sekai-kei" emerged in the early part of the 2000s as a vague catchall phrase for a certain shared aesthetic surfacing in the subcultural arts of anime, manga, and games. Although a universally agreed-on definition of what precisely constitutes sekai-kei does not exist, it tends to be used to denote a particular type of aesthetic register reliant on the structure of the romance story as the foreground for a type of world-historical, interplanetary, or international conflict. Within this style, the overwhelming emphasis is on a bittersweet nostalgia, often mobilized through the disjunction of the linear temporality of a romantic relationship—flashback, flash-forward, and multiple timelines coexisting in one filmic situation are the primary narrative devices.

The romance is invariably cast in a kind of parallelism to war, the earth, the nation, and so on, and this parallelism is the usual lever for the operation of nostalgia: through the juxtaposition of imagined or daydreamed past possibilities or lost hopes within the relationship, the positions in conflict are thrown into relief. Filmically, this style tends toward macro-aestheticization at all times: extradiegetic music and a visual aesthetics of contrasting scale are formalized features. Through the juxtaposition of hallmarks of intimacy and closeness — smallness, slowness, lightness, taciturnity, the silhouette, the sweet memory, touch, the vanishing moment — with the hallmarks of "the world" and distance — bigness, speed, heaviness, multivocality, endless differentiation, immensity, monumentality, world-time (in contrast to the time of sociality), and so forth — the tendency toward aestheticism, contemplation, and the parallelism of individual and world is constantly rearticulated. Landscape, and its relation to the individual, is a recurrent image employed in Shinkai's films, a visual configuration in which this parallelism of contrasting scale is constantly put forward.

But equally important to the sekai-kei style is the affective level at which this relation of individual and world operates. "World" here is not only "the" world but also "my" world. Thus, there is a constant emphasis in PPED on the enclosed, small, internal, psychic spaces of the individual life as one "world." The tendency toward this mentality, that is, toward flirtation with a certain solipsism, can be considered a quintessentially post-Fordist phenomenon, into which most of the younger generation in the "advanced" industrialized countries are thoroughly inculcated. On one hand, the boundaries of the world are both more diffuse in terms of the latticed networks of information, communication, commonality of the image, synchronization of everyday time, and so forth. Simultaneously, the scale of the world itself is infinitesimally smaller, mirroring the shrinking nature of the commodity unit and its increasing concentration. Hence, the world is both enormous and immediately at hand, and the position of the self is increasingly "global" in its crossfertilized contamination.

At the same time, the means of access to "the" world are increasingly mediated by a new, dense array of technologies — most importantly, the sociality on which we had come to rely for our earlier notions of individual and world are largely being replaced. For example, I might relate to an increasingly vast number of people, from a series of distant locations, with a bewildering amount of information, opinion, and affect, but I relate to them through the mobile phone, through the two-dimensional screen of the computer, and so forth. Consequently, an essential element of the sekai-kei aesthetic could be considered a new discovery of “world” — in other words, the world and all of its vast scale, its overwhelming openness, is also contained in this "cramped space" implied by the miniaturization of the object today. The perfect example of this can be seen at the beginning of Shinkai's debut film, Voices of a Distant Star, when the protagonist's voice is overlaid on the opening of the film: she dials a number on her mobile phone while her voice tells us, "There is a word — ‘world.’ Until I was in middle school, I thought that ‘world’ just meant somewhere that my cellphone signal reached."

But what Shinkai's films, and PPED in particular, demonstrate is not that "world" is discovered as an autonomous, distant field outside consciousness but rather that the world is understood as a ubiquitous connective tissue related to the formation of an "I." It is possible to discover in sekai-kei productions a merely solipsistic, isolated, fearful sociality in which "world" comes to signify everything from which one must escape. But it is also possible, and, I would argue, more suggestive, to see in PPED and its aesthetic counterparts an identification of a kind of "general intellect," an increasingly socialized knowledge involved in the constant figuration of the world and its history (Figure 2).

Figure 2. ... but in those days, I felt that the smells of the night wafting into the train, the trust I had in my friend, and the hint of Sayuri that lingered in the air were everything in the world" (sekai no subete). From Shinkai Makoto, The Place Promised in Our Early Days.

In PPED, as Hiroki, Takuya, and Sayuri walk back to their local train station, Hiroki narrates their transition from childhood. As the train pulls away from the station, Hiroki stares out of the window of the train and says, "Just close by, the world and history were changing, but in those days, I felt that the smells of the night wafting into the train, the trust I had in my friend, and the hint of Sayuri that lingered in the air, were everything in the world (sekai no subete)." This parallel of monumentality ("the" world and "history") and miniaturization (the relation of I and you as another world) again shows us the degree to which "world" here is a bundle of significations, a vehicle both of everything absolutely external as well as a series of internal affective judgments through which there is a common logic connecting them along a chain of meaning or identification, also called "world."

We have, throughout PPED, a mobilization of "world" as a contested, unstable object which is more than anything identifiable solely through its creation as a unifying aesthetic — in a sense, the film demonstrates and relies on a notion of the thickness of world as a material-semiotic field. [5] Thus, sekaikei, rather than necessarily being a reactionary retreat from the responsibility and burden of historical memory, could be read as having precisely the opposite set of potentialities at work. Because it breaks down the density of "world" as a concept toward "world" as a name for a series of malleable affective registers, sekai-kei admits and images the world and history as figuration; that is, it shows that the making of a world and its history is that world and its history. Thus, it comes as no surprise that in PPED the question of writing, rewriting, and overwriting, or "coding," is key. But as we will see, while PPED raises a series of decisive questions about our contemporary moment, not only in its narrative and associated "world" but also in its visual logic, the film itself is resolved in the final analysis through an evasion of the problems it itself articulates.

As mentioned at the beginning of this essay, PPED is not a futural projection nor a reimagined past — rather it is, in keeping with its diegetic narrative, itself a type of parallel present, a "remix" of contemporaneity. It is itself a "world," and it is this that distinguishes it as representative of a new type of creation within the anime sphere –– as a work, the traditional contours of PPED as a "story" or "plot" are significantly less important than its "world." To a certain extent this is what Azuma Hiroki, among others, has referred to as "manga-anime realism" (manga-animeteki rearizumu) — PPED is a work that rests on a world that is found only as a figuration on Shinkai Makoto's hard drive, a new type of realism whose “reality” is itself a feedback loop for its own “world.” [6] But this problematic is not merely worth considering in terms of the formal conditions of production of PPED but also as a part of its internal logic and as something that we could say is "theorized" by the film's narrative itself.

As Takuya goes on to work as a scientist in the Alliance's top-secret research division dedicated to reconnaissance and investigation of the Tower in Ezo, we are given an increasing amount of information about its powers. The Tower, it turns out, is a device intimately related to dreams. When Takuya and his coworker (and new romantic interest) Maki visit the munitions factory where Takuya and Hiraki once worked, she explains: "our world hides all these different possibilities, things that could have been, inside our dreams—we call these ‘parallel worlds’ (heiko sekai) or ‘branch universes’ (bunkyuchu)." Just prior to this, we have learned that a certain Ekusun Tsukinoe, a famous Union scientist who proved the existence of "parallel worlds," was responsible for the design and supervised the construction of the Tower. In the area surrounding the Tower, there is a space of "completely different matter," itself composed of "different universes," and between the world in which PPED takes place and the areas around the Tower, there is a constant ebb and flow of "spatial displacements with these parallel worlds." That is, the Tower is to a certain extent a spatial concretization of the dreamspaces of all the people around it. It is not simply that the Tower produces these "parallel worlds"; rather, these worlds are internal features of all organisms’ brain patterns — hence the research unit to which Takuya belongs is known as the “Brain Science Unit." The importance of this research is visually confirmed by the presence of the U.S. National Security Agency at their laboratory—the potential power of this technology stems from its use to predict future historical outcomes. However, these future outcomes are not grasped by examining a field of possibilities across linear, chronological time and computing their likelihood. Instead, PPED tells us that the "future" is predicted, or more accurately, identified, by seeing in these "parallel worlds" the results of an actual future. In other words, the ability to grasp the past, or indeed the ability to understand the future, occurs through the conceptual overlapping of another disjunct temporality on the present to a certain extent in PPED, there is no time other than the present, a type of "eternal now" that is stretched, elongated, and retracted through its imbrication with other parallel presents, an endless oscillation from one present to another and back.

Hiroki and Sayuri, who has been in a coma for three years since their "promise" to go to the Tower, dream of each other. Their parallel interior worlds overlap — and when Hiroki encounters Sayuri in his dreams, that is, when he encounters "her" within "himself," he remarks that the experience was "more real than reality" or "more present than the present" ("genjitsu yori mo genjitsu rashii'). As Sayuri's dreams shift in the wake of seeing Hiroki in her ostensibly "private" internal space, the Tower begins to inscribe its parallel realities over the existing material world surrounding it. The “Brain Science Team” are frantically scrambling to prevent the "real" material world from being swallowed up by this widening "parallel world," and, as the circle of "overwritten" matter widens (Figure 3), the chief scientist Tomizawa asks himself, “Do they mean to rewrite the world?” (“Sekai o kakikaeru tsumori na no ka?”).

Figure 3. The Tower begins to inscribe its parallel realities over the existing material world surrounding it. From Shinkai Makoto, The Place Promised in Our Early Days.

The Tower is "rewriting" the world, "rewriting" history, and destabilizing the facticity of this present, by recoding it with the endless possibilities of the parallel presents occurring in conjunction with that of PPED’s narrative. Thus, we can see the equivalent occurring on the internal level of the narrative as is occurring for the audience watching, with respect to the temporality of PPED. In this sense, the film can also be read as itself depicting the development of an animated cinematic logic essential to the affective structures implied by computerization, digitalization, immaterialization, and so forth. That is, particularly in its expressive functions, PPED is exemplary of the transition between what Paul Virilio called extensive and intensive time.

What is increasingly being replaced through digitalization, the instaneity of computerization and automation, is the logic of extensive time, which "worked at deepening the wholeness of infinitely great time," articulated in the chronological order of "past, present, and future." In its place is increasingly a kind of "intensive time," no longer marshaled across the tenses, but in the "real time" and "delayed time" of the image. [7] This is explicated in PPED precisely through the Tower as the point of mediation of "real time" and its displacement. The displacement occurring around the Tower is not a shift of the past into the future, or vice versa, so much as it is an intensification and compression of the "real time" of the narrative with other presents, including that of the audience.

One of the widely remarked-on techniques employed in PPED is Shinkai's use of the photograph as a reference point. Scenes in the film would be essentially drawn "on top" of photographic images of Aomori in a new type of digital overwriting or refiguration. That is, the processes of imagination at work in this type of visuality stem not from the imagining of "new" worlds (as in the older "extensive" form of science fiction) but rather from a new type of sensibility in its sekai-kei inflection, that is, science fiction as remix or paralleling of the present. In just the same way as the Tower rewrites or recodes the space of the "world," so Shinkai rewrites the space of "Japan" by recoding the visual register of Aomori and Tokyo. Azuma for instance remarks, "When I first saw [Shinkai's] Hoshi no koe, I thought, this is something completely different from anime thus far. This isn't a moving image, it's something more like a collection of still images that happen to be moving." [8] That is, there is a strange doubled system of visual referentiality operating in PPED (as well as in Hoshi no koe) — the still image overlaps with the audience's "real time," and is imbricated with the audience's sense of spatiality, but when the image begins to move, it does not move in this "real" time but in a displaced, parallel trajectory, thus visually "theorizing" for the audience the immanent possibility of multiple directions in the present.

Through the graphic superimposition, tracing, and doubling of the audience's "real time" and space with the "parallel world" of the animated image, PPED itself is constituted as a perfect symbolization of the supersession of extensive time/extensive space with intensive time and, by extension, a direct emphasis on history and memory as continual creation. The rewriting or redrawing of the contours of history is an articulatory act of re-outlining, redrawing the boundaries of the space of the world itself, an endless, improvised figuration in an unstable, partially determined present that is increasingly evident and visible in contemporary cognitive capitalism.

PPED articulates the "present" nature of coloniality, the temporality of the constant creation of the "here," and the new direct productive capacity of affect, gesture, and so forth. By displacing and dislocating the conceptual architecture of "our" present into another present in which the same materials are divergently organized, the film itself becomes an image of "the geopolitical postcolonial situation" that serves "as something like a paradigm for the thought of history itself as figuration, figuring something out with ‘chunks of the real.’ ” [9] That is, its strength as a creation lies not in its prescriptive capacity for reflection but in the way it performatively puts into question our inherited organization of history.

Hiraki boards a train for his home of Aomori, in preparation for his mission to fly to the Tower with Sayuri, and as we see him on the train, reading Miyazawa Kenji's Spring and Asura (Haru to shura), we hear in a voiceover Okabe stating to his comrades in the Uilta Liberation Front: "It's now clear that the Tower is a weapon over the past twenty-five years, it has become a symbol of every aspect of daily life: the nation-state, war, ethnicity, despair, and longing. But the one constant is that everyone sees it as something un reachable, something that can't be changed. As long as they do, this world won't change either." The Tower is reflected in the glass of the train, and in our screens, we see again the doubling effect of the present in PPED — the superimposition of the young man reading a classic of "our" modernity in a vehicle that is a recognizable technological innovation of "our" history, on top of which is overlaid the Tower, the symbolic ordering mechanism of "his" present (Figure 4). In this sense, Shinkai's film can be read as a replication and dislocation device for us, a way to see a series of still images, snapshots, and movements of the operation of contingency in our present, the presents within the self that are endlessly vanishing and emerging.

Figure 4. The doubling effect of the present in The Place Promised in Our Early Days: the super-impositions of a man reading "our" modernity, in an innovation of "our" history, overlaid by the Tower, the symbolic ordering mechanism of "his" present.

PPED, in this sense, structurally articulates the coloniality of the present and its irreversible location in "me" but, on the level of its narrative, in the end reveals itself as an evasion of history, predicated on a denial and unwillingness to confront situatedness or positionality. It is impossible to reverse, repair, or redeem "oneself" from the fact of the history of colonialism—in this sense, it must be said that PPED recognizes that "I," as the audience, implicitly acknowledge this in the identification of my present as the time of coloniality. Thus, in the film, the entire question of the linear flow of time, and in particular the traditional linear narrative of the beginning, establishment, and end of the colonial system, is displaced through the fragmenting of the present. Because the form of the film itself is predicated on the understanding that it is our time and us in which coloniality exists, PPED cannot be accused of being an erasure of the history of colonialism. But it does not draw this interrelated network of problems out to its natural conclusion; rather, it can be said that PPED, while a mechanism for examining the coloniality of the immediate moment, is nevertheless devoted to effacing the present, to escaping from confronting it within oneself. It is never the retrospective linear gaze back toward the moment of colonial violence that is disquieting, instead it is "our" actual present existence that gives us pause. My "self" is precisely the site of the postcolonial in the sense of its irreversibility, an existence itself always already implicated.

When Hiroki describes Ezo and the Tower early in the film, he suggests that its specular power to generate fantasy stems precisely from the fact that, while it is constantly seen, it is fundamentally unreachable. The Tower is that "place that looks so close, it's like you could reach out and grab it, but you can never actually get to it—we wanted to see it with our own eyes." They thus aim for something impossible, the encounter and conquest of "the Real." Okabe duplicates this with his argument that as long as the Tower remains unreachable as a symbol of war, the nation-state, ethnicity, and so forth, none of these things can be changed themselves. But in PPED precisely the opposite happens: The Tower is reached by Hiroki and Sayuri, she is awakened, and they do destroy the Tower with a single missile. Thus, at the climax of the film, it is not that "war," "ethnicity," the "nation-state," and so on are confronted and re-figured — they are blown away entirely as constraints precisely by the destruction of the Tower. In this sense, the Tower is not just the externalized concretization of desires, dreams, and so forth, it is within the film something inside "me," the colonizer, in which the signifying chain of "responsibilities," "guilt," and so forth exceed me and come to, in a sense, control me, and that one wants desperately to be rid of. Thus, as the Tower explodes in a massive conflagration (Figure 5), Hiroki and Sayuri float in the blue sky in the airplane of their childhood dreams and Hiroki says, in a voiceover and thus not to Sayuri but to the audience, "We've lost our promised place in this world, but now our lives can begin."

Figure 5. The Tower explodes in a massive conflagration, and Hiroki and Sayuri float in the airplane of their childhood: "We've lost our promised place in this world, but now our lives can begin." From Shinkai Makoto, The Place Promised in Our Early Days.

Here is the real dream of PPED—that there is within me a detectable kernel that symbolizes the position of being the colonizer or the oppressor that can be externalized and destroyed, so that one might begin again, free of guilt and shame. Thus, the destruction of the Tower is not so much a utopian act for a new world as it is a concentration of the desire to be free of one's own irredeemable positionality, free of the need to ask "on what is the ‘fact’ of my immediate existence predicated?" PPED confronts directly the most essential problem of "responsibility," it confronts the fact that "my" identity already contains the irreversible time of being the colonizer. In the face of this fact, PPED essentially narrates in its form its own "dream of the universe”— the fantasy of being able to start over, to find a new moment of departure wherein there is neither "place" nor "position" as such, but rather an endless and untethered subjectivity predicated on nothing more than the individual's self-positing. This incredible fear of positionality in PPED thus can show us a great deal about the function of the "coloniality of power" today, not to mention the operations of contemporary capitalism that rely on it.

It could be argued that at the climax of the film the nation has achieved reunification through the destruction of the Tower, the foremost constraint and symbolic placeholder for the border and division, in direct parallel with the reunification of Sayuri and Hiroki. But, problematically, Sayuri realizes upon reunification that she has lost her memory, her psychic life reduced to immediate experience without the intervening grid of historical memory, and thus her love for Hiroki will vanish in tandem with the Tower. This decisive concluding gesture within the sekai-kei aesthetic —this parallel reunification, or indeed the reunification of the nation on the basis of the reunification of separated young lovers albeit at the expense of the past — should seem to strike a bittersweet note, but in fact it is precisely the opposite. This loss of memory is the ultimate triumph, the fantasy of integration into a new holism in which historical memory and the experience of trauma are eliminated, the fantasy of reversibility and escape.

The Place Promised in Our Early Days retreats from its own possibilities, in that it acknowledges the only partially determined nature of the national community, the space for figuration that its need for constant reproduction establishes. Instead of confronting this irredeemable position of "I" and "we," the film resolves itself in discovering a means of being entirely free from the present, that is to say, of being entirely free from oneself. But it is not possible to simply encounter the sorrow of the history of oppression by countering it, or "overcoming" it — it is not possible to "demarcate" oneself from racism, from the history of colonialism, and so forth, such that I can discover a new, untainted position from which I can relieve myself of the burden of being myself: “the only choice is the choice between the terrifying contaminations it assigns. Even if all forms of complicity are not equivalent, they are irreducible.” [10] The unreachable place of The Place Promised in Our Early Days is not the diegetic split of north and south but rather the split within the place where the "I" can come to be, from which escape is impossible — a new politics and new sociality able to grasp and respond to the contemporary “coloniality of power” can emerge only to the extent that we hold ourselves immanent to the complicity and irreversibility contained in the formation of this “I.”

本卷Mechademia的主题为“战争/时间”,而文章主要分为三个部分:

①平行世界-巨塔-殖民性:Walker借用了南美后殖民批评中的殖民性概念,认为日本在战后经历的是一种特殊语境下的殖民性(美苏冷战、美国的东亚新殖民主义秩序和日本与之的共谋,等等)。电影的平行世界显然是后殖民的,它以承认日本的殖民主义历史与战败为前提,将1945年视为分歧点,作为民族国家的日本在之后虽然取得了名义上的独立,但却深陷分裂、安保、冷战的支配当中。影片中,巨塔不仅是日本过去的殖民历史、战败、战后被殖民、后殖民、当下、国家分裂等等的象徵,它在影像和叙事等层面还起着支配作用,Walker认为它集中体现了殖民性的运作。

②世界系-时间-图层层叠:作者先是对世界系是什么进行了概述(部分论述不是很新鲜),Walker在这里强调的更多的是恋爱关系与世界、战争等事物的并置。在电影中,世界不仅仅是世界本身,而且还是主角所感知的世界,作为物质-符号域的世界的密度可以被打破,而世界也可以被塑造、再书写、再编码...Walker讲述了巨塔的空间置换与未来预测(通过在这些“平行世界”中查看某一个实际未来的结果)功能,并认为这是一种“永恒的现在”、 是电影叙事和其他当下(包括观众所在的)的“实时”的加强与压缩,体现了广延时间与密集时间之间的过渡;作者在电影的背景写实与图层层叠这部分(感觉受到了Lamarre的影响)强调了动画对现实的再书写和密集时间对广延时间的取代,等等。

③摧毁巨塔-回避殖民性问题:个人感觉这部分是作者基于影片最后一句台词的误读,Walker论述说摧毁巨塔是对殖民性问题(也就是剧中人物和我们所处的现实中的殖民性)的回避与抹煞,以恋爱关系的牺牲(表面上为男女主的重逢)为代价,这和世界系的叙事逻辑有相当的重合部分,可以说《云之彼端》本身十分特殊。然而简单地采用“超克”的方式是绝无可能回应面对殖民性问题的,它已深嵌于日本人的身份存在当中,近代的超克之不能性已经被探讨的过多了,还是端下去罢,,,

文章中引用了很多概念,写的也比较绕,尽力总结了一下,可能还是得读原文/(ㄒoㄒ)/~~

感觉有相当的内容在花哥的日志和知乎回答里已经被讨论过了

后殖的语境,我实在是不熟悉,而作者本身又一直在影像中回环,并没有很清晰的给出一个影像与现实之间的锚点,这确实让我读起来很困难

不过,作者的论题我倒是很喜欢。日本的后殖问题,在我看来,其实就是日本民族主义的问题。我们现在说,日本是“非正常(民族)国家”,那么日本以前就是“正常(民族)国家”了吗?其实,大部分国家压根就没有“正常”过。对于所有东亚国家来说,成为“正常(民族)国家”都意味着要弥合传统与现代的身份割裂,合理解释原生于西方的“现代性”到来的这个外在冲击点,那么大家都没“正常”过。而日本的特殊之处只在于,它为了弥合这处割裂,曾发起了“近代之超克”。因此,对日本来说,它需要弥合传统、殖民时期和现代三段身份认同

从这个角度来说,诚哥的《云彼》其实非常值得探寻。诚哥对“世界系”的主要贡献就是从sf到民俗,而sf到民俗的这个转变,就发生在诚哥在《云彼》中第一次清晰想象出“日本民族国家”后。在此之前,《星之声》中出现的都是巨大而抽象的战争。而当这种战争第一次实体化为阻隔日本南北后国境线后,诚哥就放弃了SF+战争的主题,而是转入了民俗+和风物象,这背后也体现了一种民族主义的变义。从诚哥的转变来看,我或许会同意原作者所认为的《云彼》体现了对殖民性的回避

从非常粗糙和暴言的角度来讲,从80年代的“政治系”到00年代的“世界系”再到15年后的“和物系”,或许可以观照出一种国民心理的转变:80年代仍纠结于战败与国际社会的政治身份,到00年代已经彻底难以感知和抽象化,到15年后再度回归传统寻找自我认同。诚哥或许就是在《云彼》中第一次清晰想象民族国家后,感知到了这个问题的迫切性和解答的不合时宜,于是转向民俗的探寻。而民族认同的问题也在他的后续作品中隐晦地埋藏下来,并在最近的《铃芽》中暴露出他想要解答的野心

从SF到民俗的转向、以及政治想象和国民心理在新海诚创作轨迹中的体现和变化,这些解读很有洞察力,学到了

话说【和物系】有进一步的文章介绍吗?之前从来没有听说过

有趣的是,国内对沃克教授曾有过一种误读,好像他写这篇文章,证明了自己是日本动画爱好者(或,考虑到他其他的作品,“宅左”)或新海诚电影的爱好者一样。但是,沃克和拉马尔不一样,后者的学术生涯中有相当一部分致力于建立一种动画研究的新范式(从技术哲学出发的Multiplanar Image论?比起文本/影像方向),而沃克今天说他选新海诚的《云》只是对1.《云》作为日本语境下的殖民性运行机制的体现、 2. “世界系”这种美学体制的产生与运作(沃克提到詹明信对他分析思路的影响)这两个方面感兴趣。如果要尖锐的说,我觉得有这点cherry-picking的意味。更引人注意的是,教授在一开始就强调了他对新海诚及其作品不感冒,且将日本动画(Anime)反复和Japanese Cartoon(“日本卡通”)进行混用。从这里可以看出,沃克没有对受迪士尼影响的早期日本动画和后来自成一体的日本动画之间的断层与连续进行更深度的考察(拉马尔做过考古)。有点遗憾了,本来想和教授聊一聊《铃芽之旅》和新海诚作品的变迁的。一言以概之,他所在的是比较文学系,而不是表象文化研究系(学校里倒也没有这个)。

顺便在一开始调侃了一下大陆的版权法。“以学习目的翻译的作品”理论上是不会侵犯原作者的著作权的,但不知道在美国怎么样。海盗学术翻译...沃克不太介意这个就是,他欢迎翻译,对有人在意他这篇作品还有点诧异。

题外话就此打住。我问的第一个问题是,为什么他要采用南美(秘鲁)语境下由基哈诺所提出的“权力的殖民性”这个框架(尽管它在当代日本出人意料地适用),而不是从你所说的日本民族主义的角度(它的涵义、它所抒发的情感、它对“正常化”的诉求、它弥合过去-当下-未来的尝试)来分析《云》。我提到这个的时候,教授有点摸不着头脑。他并不熟悉国内从日本民族主义出发的批判话语,所以另外扯了些宪法第九条/安保与正常化诉求、自虐史观与大东亚战争再阐释之类的有用废话。沃克之后所说的让我感觉到,你们的所指有相当程度的重叠,只是能指有所不同;教授在写就本文时最感兴趣的,是日本民族的“受害者”幻想(在之后的讨论过程中,我们稍微提及了一下没有直接战争体验的日本人是如何继承/解读“先辈”/祖上的战争体验,并在不同时间重新幻想“受害者身份”的)——二战的受害者、天皇制/军国主义/大日本帝国的受害者、美帝国主义的受害者,等等——以及“过去归过去,现在的日本和以前的完全不同,存在一个断层/超克了帝国日本”这样的一种时间性认知。这种想法很显然,和中日战争-大东亚战争这种强烈殖民色彩的入侵密不可分。但是,这不仅仅是殖民性分析被用在本文的唯一理由(身为殖民者的身份早已隐含在身为日本之中...as quoted)。更重要的是,除了你所说的新海诚对日本民族国家的清晰想象、以及日本南北内战的实体化之外,沃克教授特别强调:新海诚(ver 2004.)所想象的日本南北分裂,实际上是非常吊诡的——纵使我们可以将日本划入受美利坚治世影响,将其纳入后殖民的框架内,做一种“(由美苏冷战导致)南北分裂的平行历史作为分离自现实的当下-而这种当下之中,殖民性是其运行机制”的分析,但是南北分裂的实体化(及战争)却发生在战后殖民体系才刚刚崩塌的朝鲜半岛,而不是不曾经历本土作战的北海道-本州;朝鲜半岛生活的人们显然更符合“殖民主义-冷战/后殖民主义的受害者”这个定义/感知,但是新海诚却在他的虚构幻想作品中将这种(朝鲜民族的?)现实挪用到了日本民族之内,进行了一种“受害者”幻想机制运作下的挪用-野合。日殖时期的朝鲜/东南亚/中国...这是新海诚作品中那个不可避免的他者-受害者,但新海诚电影中,却是日本民族扮成了受害者。这个部分或许是接近你所说的“现实的锚定”。

下一个讨论的问题和“世界系”有关。我提到在教授的文中,他除了侧重世界与个人的规模差异与并置之外,还着重提及了情感层面对世界的认知想象等等。这和柄谷行人的“内面”(世界系主角的形成?)“颠倒”(通过并置)“风景的发现”(新海诚的[世界系]风景?值得注意的是,在柄谷行人的论述中、和新海诚的电影中,北海道都作为新的风景被重新发现)等等概念不谋而合,但是教授却没有引用任何柄谷行人的内容(也没有在分析内容上和加藤干郎的新海诚-可塑cloudscape论之间有所重叠...他的影像分析更贴近拉马尔的多平面图像论)。他引用的是东浩纪。沃克解释说他之所以引用东浩纪,是因为他当时在翻译学习东浩纪的德里达论(他说,东浩纪近年来变得反动了些。),而他的动漫现实主义一说,和沃克眼里的世界系作为一种新美学体制,有着类似的论点。当我谈到柄谷行人《日本现代文学的起源》对新海诚本人的影响(据2016年的访谈)时,教授有些吃惊;学术作为一种现实介入,在这里体现的更加。沃克教授在谈到柄谷行人的时候,不仅强调风景这种文学装置的形成,而且还强调日本(!)民族-日本(!)现代文学在这里的形成;某种程度上,世界系风格是高度日本民族主义性的...沃克在谈到新海诚的风景时,将“风景的发现”回溯到了1960年代日本新浪潮、“风景论”与城市影像实验电影上面。我们没有过多地讨论社会层面的消隐,或个人不再通过社会这个中介认知世界(或社会的世界)这一点。不过,我觉得世界系和日本红潮过后个人介入社会的不能性之间的关系,值得分析一下。实在是可惜,因为教授没有看过新海诚的其他作品,所以我们没办法聊新海诚世界系的变迁,或者“风景”的变迁(科幻到和风...)怎么说呢,沃克教授虽然壮硕如棕熊,但并不是桶子那样的肥宅黑客...he simply doesn’t know.

三十分钟的谈话,时间也没剩多少了,在最后我抓紧和教授聊了聊新海诚作品中的创伤-疗愈主题(早期新海诚是一方面,后311的新海诚是另一方面),威胁/暴力的外部性,以及将新海诚与村上春树对比的可能。这两位在很多人眼里已然成为了“新时代日本国民作家/导演”一般,而在我看来,新海诚和村上春树——借用赵京华教授的论述——作为知识分子(知识左翼?大概不是罢)介入现实政治的历程很类似。对于村上春树,那个至关重要的年份是95年(《刺鸟人》篇出版、沙林毒气...),而对于新海诚则是2011年3月11日,东日本大震灾。新海诚谈到过村上春树作品对他的巨大影响。有趣的是,《云》中日本南北分裂的时间点,1973年,不仅是中东石油危机的那一年、浅间山庄事件的后一年、以及新海诚的出生年份(或许这暗示了他的一种身份认同?),这还是《1973年的弹子球》的母题,其中,我认为,1973年是一种“缓慢渗透的停滞”(意味深) 的隐喻。不过如果拿村上春树的《奇鸟行状录》来和新海诚的《铃芽之旅》对比,则可以发现两人之间的巨大差别:无业而被社会排除在外的冈田亨通过与间宫中尉(日本的殖民史)的接触、以及下降到井底(在我眼里,这是一种转向发现[自我]内部的隐喻,比起之前作品《球》或《世界尽头与冷酷仙境》里的外部威胁),了解到了绵谷升的实质(如林少华所说,暴力,或,一个延续的结构性的暴力),并最终决定反抗绵谷升。而新海诚总是倾向于将暴力或威胁作为一种外部的(或者说可以被排除在外的)存在进行表达——打开了的,或被打开的门,在门的那一侧的蚓厄...某种程度上,这可以被同时视作一种应对创伤的日本特色方式、以及,“日本民族主义的变奏表达”。其实,拿《海边的卡夫卡》来作比较或许会更好一些(这本书里所采取的十五岁少年/痴呆老人的主视角、以及对创伤议题的处理,要比《鸟》更模糊些,或许,和《铃芽》的观感更相像),但是我还没读完这本书,所以不好下结论。个人而言,我是十分接受这种解读方式的,但是我首先考虑的不会是“日本民族主义的变奏表达”这个角度:大概这和我悲情主义式的观影共情倾向,以及《铃芽》上映当天银幕外的体验有关——本校的Emergency Mass Notification System向全体师生推送了一位大一新生不幸的死;他在宿舍猝死。在同学或宿管发现他的遗体前,没人会知道他的死,而若是没有这种学校的推送预警系统,也没有更多的在校者会知道他的死。没有手机预警,震灾就算已经发生,也会停留在屏幕的彼端,进而说,作为一种看似“外在的存在”,时刻准备着以高调的姿态入侵现实。而这种戏里戏外的、极富力量的侵入对我的影响,深刻的创伤,或许是导致我一开始对“有格差的社会暴力”的有意识忽略与遮蔽的原因。

抱歉写了这么多读起来费劲的话。要是能在和沃克教授聊天时做个录音就更好了,可惜没做。

时隔半年才做进一步的回复,冒昧打扰了。