2023-6-26 16:54 /

萌就完事了?

——在一零年代的歌曲和MV中掀起一股“哈日风”

原作者:安娜·玛蒂尔德·索萨(Ana Matilde Sousa)

文章原名:Just a Cute Vibe: Producing a “Weebwave” in 2010s Songs and Music Videos

翻译:FISHERMAN

原文链接(Project MUSE)

译者按:文章后半部分内含相当程度的风格化翻译,或许会给大家带来不适,在此提前声明。如果可能的话,烦请各位读者不吝赐教,对文章中不妥、不准确的翻译予以斧正,谢谢!

十年前,一首如梦如幻的、有着轻柔人声和怀旧电子流行连复段的颂歌【译注1】在Tumblr(汤不热)上疯传——彼时,它还是一个欣欣向荣的,以身为同人圈、亚文化、和互联网社会正义运动的大众中心而闻名的微型博客网站。[1] 这首歌,便是加拿大音乐人兼艺术家Grimes的第三张录音室专辑《Visions》(2012)的主打单曲“Genesis”。出生于1988年的Grimes原名克莱尔·布歇(Claire Boucher),而她现在的名字则是被用于表示真空中光速的小写斜体字母“c”。[2] Grimes自导自演的“Genesis”歌曲MV于洛杉矶摄制而成;它受到了迷幻的博斯式(Boschian)影像和粉彩颓废(pastel grunge)美学的影响。[3] 视频中,Grimes和她的女伴们乘着一辆凯雷德SUV穿越沙漠,挥舞着宝剑和晨星锤,看起来酷的没边儿。布鲁克·坎迪(Brooke Candy)戴着一对白色的[Contact Lens],涂着红色唇彩【译注2】,蹬着一双好似要将她捧上天的厚底高跟,穿着最终幻想风格的银色盔甲走在大街上。在坎迪肆无忌惮地吮吸冰棍的同时,她那令人震惊的及膝粉红脏辫垂散在其身体周围,就像一挂手工编织的窗帘。在另一个片段中(见图1),穿着超大尺码的水手服夹克衫、背着龙猫背包的Grimes在加长豪华轿车的车尾和朋友们一起开着派对,她的肩上还环绕着一条黄金蟒——这致敬了小甜甜布兰妮在2001年度MTV音乐视频大奖上的演出。[4] Grimes将她的头发扎成了迷人的金色双马尾长辫。随后,她和一群倦态的嬉普士(hipster)在树林中摆起了造型。接着,她玩起了手持烟花筒,而后,挥舞着一柄烈焰圣剑,就像神的使者一般。

图1. “Genesis”MV中,Grimes、布鲁克·坎迪、及其随从的截图。

虽然名为“创世纪”,但“Genesis”绝不是在西方流行MV中唤起一股诱人的“酷日本风”的起源。[5] 这份荣誉很有可能属于昙花一现的The Vapors乐队的“Turning Japanese”,它“被广泛认为是流行歌曲历史中最愚蠢的作品之一”[6]:曲中包含了臭名昭著的东亚短乐句,和其他东方主义的刻板印象。[7] 自上世纪80年代以来,援引日本流行文化的MV大多采用了下文所述的两种模式。一方面,或许是受索菲娅·科波拉的电影《迷失东京》(2004)的成功启发,有诸多MV将以“西方人在东京闲逛”为主题的漫游者(flâneur)传统风格作为其基调。在这些作品中,酷感(coolness)成为了东京城市森林的自然组成部分:酷感,既是传统意义上(相对而言)的——例如杀手乐团(The Killers)的“Read My Mind”,也是流行文化意义上的——例如黑眼豆豆(The Black Eyed Peas)的“Just Can’t Get Enough”。另一方面,一些MV直接引用了“日本制造”的流行文化:它们通常由艺术家本人/他们动画化的另我人格主演,或将日本流行文化和歌曲主题联系起来,例如野兽男孩(Beastie Boys)的“Intergalactic”,或t.A.T.u.的“Gomenasai”。最著名的,是那些由动画制作公司为之绘制画面的MV。例如,法国双人组合Daft Punk邀请松本零士和东映动画共同制作而成的《Interstella 5555》(2003)、小甜甜布兰妮的“Break the Ice”(2008)、以及法瑞尔·威廉姆斯和日本艺术家村上隆、Mr.和Fantasista Utamaro的合作MV “It Girl”(2014)。

“Genesis”并不是一部日本动画。尽管如此,Grimes的日本灵感来源——从草间弥生到Kyary Pamyu Pamyu,从《阿基拉》到《塞尔达传说》——解释了为何她曾发推说日本是她的“精神祖国”的原因。[8] “Genesis”在2012年年初的发布使之成为了当代艺术中的一个定义宽泛的运动的桥段编码器(trope codifier),而作者将这种艺术运动称为:「哈日风」(weebwave)。起初,“御宅族”这一术语描述了所有痴迷于日本动画、漫画、电子游戏、以及其他日本流行文化的爱好者,无论他们是不是日本人。然而,根据Know Your Meme网站的说法,在2002年左右出现了一个与“御宅族”相竞争的网络歧视语,它基于爱好者的国籍进行了切割:这一词汇便是“Wapanese”,即“wannabe Japanese”(想成为日本人)的缩写。[9] 大约在2004年,“wapanese”一词在英文匿名贴图讨论版4chan上变得极为流行。但“wapanese”也成为了4chan用户之间发生的许多冲突的根本原因,以至于版主引入了一个过滤器,它将“wapanese”替换成了一个新词,也就是“weeaboo”。[10] 就其自身而言,“weeaboo”是一个无意义的词汇。它首次出现在尼古拉斯·古雷维奇(Nicholas Gurewitch)的网络漫画《The Perry Bible Fellowship》里,其中,一个人物大胆地说出了“weeaboo”一词,而作为惩罚,这个人物被暴徒绑了起来,抽打屁股。[11] 在4chan版主出手后,“weeaboo”(哈日族)开始被用作可鄙的“wapanese”的同义词,经年累月,它便缩短成了“weeb”。

没过多久,「哈日族」便从侮辱变成了一种自嘲的幽默;它甚至被某些人视为一种“荣誉勋章”。基于一定的自我民族志研究,如今,作者认为:在西方社交媒体上,哈日族/weeaboos/weebs的风头已经盖过了御宅族/otaku。“哈日族”一词的存在本身表明了一种前所未有的需求,即:将民族-种族或其他意义上的“正统”爱好者和那些通常被认为是“没有来由地便挪用日本流行文化产品”的人(甚至这些人自己也这么认为!)区分开来。谈到作为哈日风桥段编码器的“Genesis”时,作者有意地描述了这种“浮于表面”/“浅尝辄止”(大意如此...缺乏更准确的描述语)的挪用。“weebwave”中的“weeb”(weeaboo的缩略语)展现了21世纪(日本的)御宅族向世界的哈日族的演变、以及在此基础上向一种更酷(coolified)的新版身份的转变,而对于认同这种身份的人而言,哈日感更像是一种表演风格/噱头。在哈日风中,媒介化的“日本”(而非真实的日本)成为了一种朦胧的、灵活的、非固定的影像:它、和对流行文化和网络文化数不胜数的引用,一并构成了数字原住民(digital natives,也就是千禧世代、Z世代、和即将登上舞台的α世代)意识的“自然”/“显明”的一部分。此外,尽管哈日风的载体并不局限于歌曲和MV——可以想到的是,某些种类的全球漫画(global manga)符合哈日风的定义,并且,观众还可以在其他电影和当代艺术中找到哈日风的影子——这些歌曲和MV对那些在YouTube或Instagram之类的网站上花费了大量时间,从而绕过了传统文化影响方式的年轻观众来说尤为重要。[12] 因此,本文使用的研究案例是那些「可传播性」[13] 明显的歌曲和MV(从它们的爆红可以看出),也就是由出生于八十年代初期至九十年代中期的艺术家,如Grimes、Vektroid(和她参与的蒸汽波运动)、乔恩·拉夫曼 [Jon Rafman](和他的创作伙伴Oneohtrix Point Never)、Princess Nokia、Josip On Deck、以及Doja Cat创作的作品。

这些艺术家和一般的哈日族甘愿被“日本化”的这种“自然感”本身就有些违和,特别是当我们考虑到这一点时:诸如罗兰·凯尔茨(Roland Kelts)的记者经常把日本动画和漫画在世界范围内的成功称作日本对西方文化霸权的“入侵”或“复仇”。[14] 或许正是因为这种成功和文化意义上的“不洁”之间的联系,被视作“跨国越轨行为”[15]的“日本化”十分适合抵抗“那些恐惧地将大众文化——以及它对极端现代主义价值观的‘玷污’或腐蚀——与女性和酷儿的身体联系起来的意识形态”[16](被联系起来的,还有种族化的、非白人的身体)。值得一提的是,本文提及的大多数艺术家都在某一方面上同「酷儿性」(queerness)有关,无论是性(sexual)和性别(gender)意义上的酷儿性、还是通常意义上对社会角色的不顺从。例如,Princess Nokia对其双性恋、非常规性别(gender nonconformity)和混血儿身份持激进态度;Vektroid是一位跨性别女性;Grimes将自己塑造成了一位后人类主义双性性格者(androgyny);Doja Cat和Josip on Deck是两位通过冲击式幽默(shock humor)来挑战过于简化的种族与生理-社会性别角色概念的黑人艺术家。更何况,这只是冰山一角:还有众多的异装/跨性别西方艺术家在其作品中大量引用日本流行文化和萌文化【译注3】,例如Ladybeard[异装]、和SOPHIE[跨性别]。

哈日风的另一个根本特征,是对DIY美学、同人圈用语、以及卧室制作(bedroom production)的强调。的确,尽管千禧世代可能位于「产用革命」(produsage revolution)[17]——这指的是通过一系列愈来愈容易获取的资源和工具,来在线消费信息、并以数字方式创建和/或共享内容——的中心,但有学者指出,“对年青一代来说,互联网主要和那些由企业提供、且注册后才能享用的服务相关”,而这则否定了“上述新媒体内容在某种程度上比在传统‘旧’媒体中发现的内容更不受限制”的天真假设。[18] 因此,尽管可以将类似“Interstellar 5555”或法瑞尔的“It Girl”这样由专业人士制作的精良作品归类为哈日风的一部分,但本文关注的是那些特殊的作品,其中,“日本化”、萌化和业余化过程似乎凝聚成了一种立场:它呼应了由晚期资本主义(或新自由主义)为全球社会-生态结构带来的毁灭性影响所促成的,对西方现代性和个人主义更为广泛的祛魅。可以说,祛魅同样存在于这种凝聚现象令人不快的边缘部分,即日本动画同人文化和incel(非自愿独身)以及另类右翼运动之间令人不安的交集,纵使这种祛魅和其他的相比有着立场相反的政治议程;本文中,拉夫曼的案例诠释了这种交集。然而,在进一步分析之前,作者认为有必要更加深入地探讨御宅族和哈日族之间的区别——部分前文所述的矛盾冲突,早已植根于这种差别当中。

御宅族和哈日族 / 御宅族vs.哈日族

在上一章节的介绍部分中,作者将“哈日族”一词的起源归因于将日本籍的动漫和电子游戏爱好者(即御宅族)和同类产品的全球爱好者区分开来的必要性。不过,这种简单的区分并没有捕捉到御宅族和哈日族的对立中的细微差别。御宅族将他们的亚文化爱好维系在“合适”的场所当中(也就是说,这些场所被控制在非爱好者所处的空间之外,或通过其他方式和非爱好者空间分隔开来,典型的例子有秋叶原街区、和东京国际展示场)。相比之下,典型的哈日族夸张地、令人厌烦地、没来头地痴迷于日本流行文化,而他们的嘴中则不停地蹦出“斯国一”(すごい/厉害)、“卡哇伊”(かわいい/可爱)、“desu”(です/是也)、“巴嘎”(马鹿/白痴)之类的呓语。按照这种定义,外国人也可以成为一名御宅族,前提是他们表现得好的话——正是哈日族爱好内驱力(fannish drives)的过度外部化,使他们失去了“正统的”文化成员资格。WikiHow上甚至有一篇《如何避免成为哈日族》的文章...这种对哈日族的普遍排斥由此可见一斑。[19]

考虑到“大众想象中的御宅族被日本社会压迫,从而被迫过着双重生活”[20]这一点,御宅族和哈日族之间的裂痕在“日本化”的同人圈中表现为学者凯西·布里恩扎(Casey Brienza)所言之“民族-种族正统性的操演”。[21] 通常情况下,这种裂痕亦是性别化的,因为刻板印象中的哈日族总是女性,或因其外表和品味而被女性化。实际上,在谷歌上搜索“哈日族”的返回结果,是具男性气质的西方男子crossplay(跨性别角色扮演)成鹿目圆和月野兔这样的女性动画角色的图片。根据Urban Dictionary上排名最高的词条所述,哈日族的定义之一,是:“一位喜欢观看CGDCT动画,有自己的二次元老婆和老婆抱枕,并且痴迷于日本的非日本籍男性。”词条补充道:“哈日族人畜无害”,“他们知道自己被许多人厌恶,但一点也不在乎,因为他们知道自己很斯国一。”[22] 这种定义指出了对零零年代御宅族文化产业“萌化”的偏见,即:认为CGDCT(Cute Girls Doing Cute Things,直译为“可爱的女孩子做可爱的事”)动画和漫画的繁荣、以及动画和漫画的女性化所带来的影响,是对“严肃的”、顺从性别(角色)的、喜欢体育类动画和科幻小说的男性御宅族的威胁。[23]

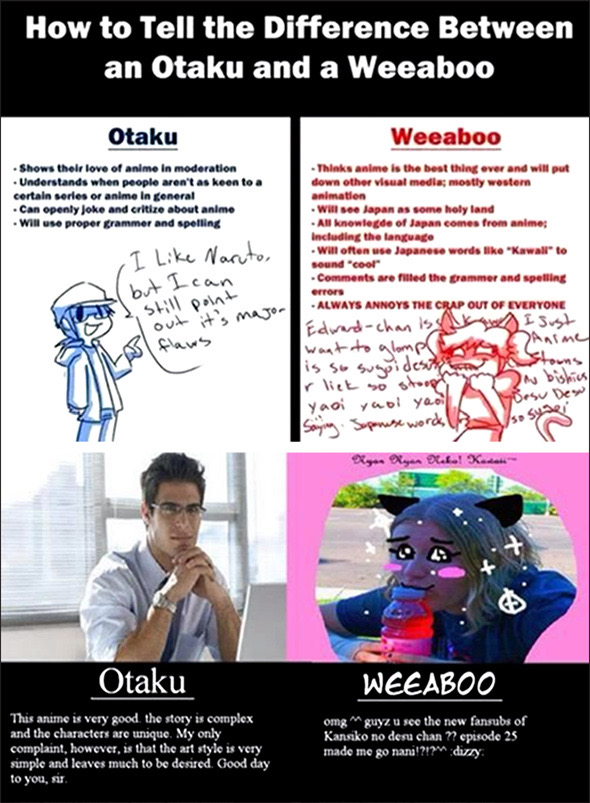

讽刺的是,自上世纪80年代以来,日本的御宅族一直在忍受着自身的生理-社会性别问题的折磨,而他们则被大众媒体病态化为患有二次元禁断综合征,不喜欢“正常”(有血有肉的)女性的失败娘炮[24]——这在“御宅学”领域中是众所周知的。如今在21世纪,这种通过女性化受害者从而达成的污名化——体现在受害者和异装、以及“恼人但无害”的刻板印象的联系当中——似乎转嫁到了哈日族身上。与此同时,创造并塑造了“哈日族”一词含义的西方人用一种“新发现”【译注4】的社会活力和阳刚之气改造了原初的日本御宅族,而事实上,他们在日本从未拥有过这种力量。就此而言,网上流传的各种图画/拼贴画十分具有启发意义:它们用类似迷因创作的方式对御宅族和哈日族进行了比较。以图2中的两组迷因为例:图2上半部分题为“如何分辨御宅族和哈日族”的梗图并排比较了一位低调的男性御宅族和一位歇斯底里、语无伦次的女性爱好者,前者正理性讨论着一部日本动画,而后者则叫嚷着“bishies”(即美少年的日文罗马音缩写)和“yaoi”。图2下半部分中的哈日族被叠加在其面容上的涂鸦(二次元眼睛、腮红、和星光效果)萌化,而此处的御宅族则被描绘成了一位英俊、自信、方下巴的商务人士。在这两个案例中,御宅族-蓝色调和哈日族-粉色调的色彩设计加强了御宅族和哈日族之间作为男性与女性的对立。

图2. “御宅族vs.哈日族”迷因的两个案例。

作者之所以说这张配图具有启示意义,是因为它触及了“哈日族”作为贬义词兴起的另一个关键层面:很大程度上,哈日族一词的兴起和反对腐女子同人圈(由喜爱耽美作品的妇女和少女组成)在零零年代至一零年代间日益增长的话语权有关。[25] 历史上,在与文化产品(例如美国漫画,它不待见男同性恋色情,并将其视为一种入侵[26])相关的、以异性恋-男性气质为编码的同人空间中,女性爱好者被完全忽视、或为了避免成为嘲讽对象而刻意使自己被忽视。随着LiveJournal和Tumblr等等对腐女子友好的线上空间、以及FanFiction.Net与Archive of Our Own (AO3)这样专注于同人小说的(虚拟)场所的兴起,腐女子的这种同人驱动力在西方获得了前所未有的知名度。诸如图2所示的例子表明了对腐女子视觉与话语能见度的强烈抵制,在此过程中,御宅族的地位以牺牲女性爱好者为代价而得到提升——尽管在日本,御宅族过去是、现在也是一个被污名化的身份,而且还是一个女性化的身份。

DIY同人文化、萌感、与“日本性”

正如“Genesis”MV所展示的那样,卧室制作,而非专业音乐或动画工作室,才是哈日风的核心。对自导自演的业余影像片段、“拙劣”的编辑技术(画中画叠加是最受欢迎的技法之一)、以及爱好者DIY工具的频繁依赖,使得哈日风和以社区与合作为导向的创客/黑客/开放运动(例如,自由软件运动)的实践行动相一致,而这则——在理论上,如果不总是在实践中——表明:这些运动反对商品化的、被“收缩包装”的艺术与文化。[27] 因此,对这些艺术家而言,MV扮演着三重角色。一方面,这些MV本身不仅构成了一种基本的艺术表达(而不是单单作为歌曲的副产品),而且它们通过对日本动画、漫画、电子游戏等文化产品的引用,宣告了其自身对某种亚文化的、以世代性(指千禧世代及其之后的人群)为主基调的身份的归属。[28] 另一方面,这些MV表现出对追求影像完美与整洁的目的论“技术-实证主义创新叙事”的拒绝,而这则为它们对业余爱好者制作技法的偏好提供了正当理由。[29] 在Grimes的案例中,这种后数字的精神气质似乎与日本动画和电子游戏的后人类主义氛围相融合,而弥漫在“Genesis”MV当中的这种氛围亦在Grimes于2015年发行的专辑《Art Angels》当中收录的许多后续MV(例如“Kill V. Maim”或“Venus Fly”)里得到了延续。[30]

和之前的专辑一样,Grimes亲手操办了《Art Angels》的艺术设计,只是这一次,日本流行文化的影响愈加强烈。专辑封面的数位图画描绘了一具漂浮在太空中的蓝色外星人头颅:它有着尖耳朵、麻花辫、以及三只巨大充血的二次元眼睛。封绘右侧的侧标部分中有一只粉色头发的动漫【译注5】精灵。唱片内附带了各种插图,它们充满了对卡哇伊文化、古典奇幻(high fantasy)、网络迷因和涂鸦艺术的引用。Grimes像巫师一样在巨大的文化记忆坩埚里搅动着她的魔法药剂,在这儿,高雅艺术与“数字民俗”在全球性的操演中邂逅,过去和未来交织在一起,变得扁平、无法区分。[31] 但这并不止于此。诚然,自两人首次在2018年度的Met Gala(纽约大都会艺术博物馆慈善舞会)上公开露面以来,网上已有大量笔墨描绘Grimes和地球上最富有的人之一、特斯拉CEO埃隆·马斯克之间那不太般配的恋爱关系(这对情侣的第一个孩子于2020年出生,他被命名为X Æ A-12,颇具争议)。两人的关系激怒了Grimes的粉丝,他们认为:Grimes与敌人同床共枕(字面意义上),背叛了她的进步左翼意识形态。[32] 然而,Grimes继续在媒介环境中发挥着她引领潮流的影响力,并迎合着千禧世代观众的欲求——后者渴望着那些用Y2K垃圾数字美学和互联网所孕育的亚文化讲述的科学-幻想故事。

Grimes随后发行的专辑加剧了日本流行文化在其兼收并蓄的虚构作品(concoction)中的普遍性。于2020年发行的专辑《Miss Anthropocene》(这是“厌恶人类者”/“misanthrope”和“人类世”/“Anthropocene”的双关[33])在Grimes亲自绘制的封面上再次呈现了一位以2D和3D形式渲染、长有双翼的动漫风女性角色:它是人为气候变化的拟人化形象。第一首单曲“We Appreciate Power”的MV(仅在日本发行的CD中收录)为整张专辑定下了基调:在数个片段中,Grimes打扮成了一位抑郁的“e-girl”(直译为电竞少女),在赛博朋克风格的背景前抱着一只三丽鸥风格的可爱毛绒玩偶;接着,她和HANA(Grimes的合作者及巡回演出的伴唱歌手)一起,穿着Plug Suit(EVA中的战斗服),拿着复合弓、和一把像《少女革命》中那样的西洋剑,摆出了“战斗美少女”般的姿势。[34] 另一部MV“My Name is Dark”则直接收录了《EVA》和人气CGDCT作品《小林家的龙女仆》的动画片段,以及“网红作品”《美少女战士》的Snapchat滤镜。《美少女战士》亦在“Delete Forever”的MV中出现,在视频中,看起来就像“游戏里的最终BOSS角色”一样(根据一则评论所言)的Grimes在可能是月亮城堡废墟的景象中唱着一首凄美的歌谣。[35] 此外,Grimes在YouTube上将“My Name is Dark”的MV命名为“(NOT thee OFFICIAL VIDEOOO, just a cute vibe) Xxo”[大意为:(并不是官方视频捏,萌就完事了)Xxo]——该标题的网络用语特性(Xxo意为“亲吻和拥抱”)加强巩固了她身为一个在社交媒体上随意与粉丝沟通交流的“卧室制作人”的灵韵。[36] Grimes的风格便是如此,尽管她现在已是一位全球超级明星,并且,她的许多视频早就从小成本MV变为了大制作作品。

对日本动画的引用在“Idoru”的MV中达到了巅峰。该MV发行了稍短(5分19秒)和稍长(6分54秒)的两个版本。“Idoru”的歌名,是短语“I adore you”(我爱慕你)和歌曲所引用的威廉·吉布森之赛博朋克《桥梁三部曲》第二部小说书名的双关,并且这部小说献给的正是吉布森的女儿克莱尔(即Grimes的出生名)。[37] 这部MV混合了两类影片。一方面,MV中出现了这样的画面:明显怀有身孕的Grimes穿着一条飘逸的白色连衣裙,在扁平的粉彩背景前舞动着,在数字樱花花瓣的风暴中举着一把剑;她戴着一对异色瞳的[Contact Lens],并将头发扎成了双马尾。另一方面,MV节选了像日本电子游戏《尼尔:自动人形》这样的邪典作品的、以及标志性的酷儿动漫情侣天上欧蒂娜和姬宫安希(同样引自《少革》TVA和剧场版动画)的相关片段。和“My Name is Dark”一样,“Idoru”的MV在YouTube评论区激起了大量有关哈日族的幽默回复:“所以你是在说Grimes和埃隆·马斯克是骨灰级哈日族咯?赞成。”[38],“这就是提供预算给一流哈日族夫妇的后果。”[39],“Grimes的神作使哈日族再次变酷。”[40]...。这两部MV都专业地(再)生产了包括Cosplay,同人艺术、GIF图和AMV制作(即“Anime Music Videos”/“动画音乐录像”的缩写)等活动在内的同人活动的自发DIY美学(spontaneous DIY aesthetics),而为了达成这种(再)生产,它们使用了数字视频滤镜和日本动画、电子游戏的画面,并采用了粗暴的画中画叠加技法来刻意创造一种“互联网丑陋美学”。[41] Grimes的粉丝认可这一点;正如一则YouTube评论所言:“她的男友是地球上最富有的人之一,但她依然坚持制作这些‘低成本’DIY视频。我就喜欢这点。我们爱戴这位谦逊的女王口牙。”[42]

这种谦逊感既是真诚的,亦是Grimes的展示策略:通过援引她这一代人喜爱的日本动画节目或电子游戏、于特定时期(即平台流行期)频繁出没在他们选择的社交媒体平台上(例如,Grimes先是在Tumblr上创建账户,然后转战Instagram,最近又在TikTok上注册账号)、并运用同人圈自身使用的“产用”工具,Grimes营造出了一种“她是自己人”的感觉。比如说,两部发行于2020年的歌词MV(Lyric Video本身便是一种相当爱好者化的表达方式)“Darkseid w/ 潘PAN”和“My Name Is Dark (Russian Lyric Video)”似乎使用了Blender或MikuMikuDance(一个发源于日本虚拟网络名人初音未来同人圈的免费软件项目)的3D动漫模型。此外,由于COVID-19疫情封锁,Grimes决定通过Wetransfer来和她的粉丝分享“You’ll Miss Me When I’m Not Around”MV的原始视频素材:她在绿幕前表演的片段。正如她所言:“大家都处在封锁之中,所以如果大伙感到无聊并想学点新东西的话,我们可以为任何想试着用Grimes的视频片段制作作品的人发布一部过往MV的原始素材。”[43] 我们还可以在她的Instagram页面上找到这种合作与DIY的精神气质:Grimes在个人主页置顶了一条IG限时动态,专门介绍和她相关的同人艺术。总而言之,Grimes“使哈日族变酷”的事实体现了哈日风的一个关键特征:它酷化了(coolification)一种特定世代的亚文化,并在某种程度上捍卫了后者,而根据定义,这种亚文化是资本主义全球化令人尴尬且一点也不酷的副产品——乃至其神经官能症。

另外,通过重拾“次要且通常不光彩的情感”[44]、以及像“萌”和“美”这样与女性气质相关的美学(这一实践往往与“怪异和怪异”[45]的表达方式相结合),Grimes亦例证了当代艺术界和文化界的其他艺术家常用的游击战略。2013年,艾莉西亚·埃莱尔(Alicia Eler)和凯特·杜宾(Kate Durbin)就女孩和年轻女性在网上精心搭建个人空间的战略手段撰写了一篇名为《少女的Tumblr美学》的文章——Grimes正是从这种小生境空间(niche)中脱颖而出,而如今,她仍在复制着Tumblr少女们的这种创作方式(modus operandi)。[46] 尽管她们没有明说,但埃莱尔和杜宾通过大量引用Live Journal和Tumblr用户蓝可儿的悲剧性死亡事件,将“少女的Tumblr美学”框定在了幽灵学的范畴内(并因此在文章评论区激起了公愤)。有趣的是,德里达在《马克思的幽灵》(1993)一书中首创的幽灵学(hauntology)概念本身就曾被称为“一种可爱[cute]、有趣的本体论游戏”,而幽灵学则促使人们将注意力转向“萌”和“美”在植根于零零年代初期音乐界的幽灵学美学内部所扮演的,很大程度上被忽视的角色。[47] 幽灵学音乐开创、并在一定程度上产生了许多塑造了一零年代声景的互联网音乐微流派,如Witch House(女巫浩室)、蒸汽波、以及某些类型的另类嘻哈。作为幽灵学音乐特征的「谱系回溯」(genealogical throwbacks)[48]并不是什么新鲜事,但正如西蒙·雷诺兹(Simon Reynolds)所言,「当下」与「被引用内容」之间的时间差似乎在缩短。“诚然,从文艺复兴时期对罗马和希腊古典主义的推崇,到哥特运动对中世纪的援引(invocation),先前的时代有着它们自己对古代的迷恋。”雷诺兹解释道。“但人类历史上从未有过一个社会如此痴迷于自身的即时过去的文化产品。这便是复古主义与历史上的古董主义(antiquarianism)的区别,即:对出现在鲜活记忆中的时尚、时髦、音声和明星的迷恋。”[49] 在日本流行文化的全球传播被互联网的发展和民主化加强的背景下,上文所述的时间邻近性(temporal proximity)为日本流行文化的幽灵化铺平了道路——将它幽灵化的,是那些对它记忆犹新的西方群众,也就是在一零年代步入成年的千禧世代。

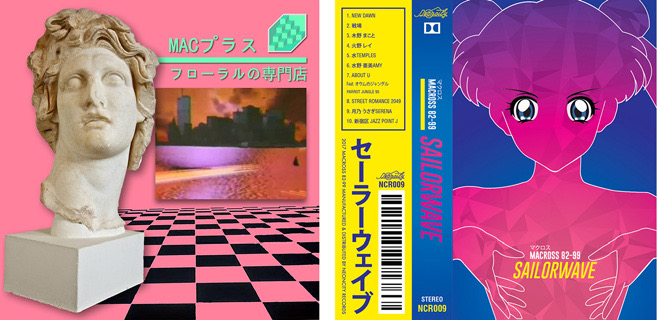

日本流行文化的幽灵化在蒸汽波这一音乐微流派中显而易见,后者通过运用东亚影像与“未来过去”式(futurepast)消费者文化、赛博资本主义下的流离失所、以及技术-东方主义的关联,刻意营造了一种高度的“后现代感”。[50] 这种在“使东西方之间的信息和资本流动更加频繁的新自由主义贸易政策下”[51]发展起来的技术-东方主义,是由西方对亚洲化的未来的想象、以及日本在建构和商品化日本性的过程中的「共犯的[自我]异国情调」[52]所塑造的,而日本则成为了西方和自我眼中的某种后现代象徵。的确,根据人类学家玛丽莲·艾薇(Marilyn Ivy)的说法,“后现代主义”是八十年代日本广泛流通的信息商品,而它则是由像浅田彰这样的“新学院派学者”或“后学院派学者”在日本大众媒体上的走红所推动的。后现代主义在日本的流行含蓄地庆祝了“本国超克[西方]现代性和[西方]历史的巨大成功”,而正是西方现代性与历史剥夺了日本“羽翼丰满的主体地位与历史能动性”。[53] 因此,蒸汽波艺术家对日本动画角色、日文字符、以及其他群体匿名(corporate anonymity)和逃避主义怀旧标志(例如购物商场,或九十年代电视节目的影像)[54]的运用表明:真正使他们着迷的,是自带「無国籍性」(mukokuseki)和「文化無臭性」(cultural odorlessness)[55]光环的日本性概念——换而言之,(他们爱的是)后现代的日本性或后现代性的日本性,而不是任意一个符合史实的、国家意义上的日本概念。美国电子音乐人Vektroid(本名蕾蒙娜·泽维尔[Ramona Xavier])在2011年以别名Macintosh Plus制作发行的典型蒸汽波专辑《Floral Shoppe》(此为专辑英文名/英译名,中文常译为“鲜花专卖店”)严格意义上的日文原名为《フローラルの専門店》,并且专辑内的所有歌曲均以日文命名(封面见图3左半部分)。在SoundCloud和Bandcamp这样的在线音频分发(享)平台上也有一个完整成熟的流派,即催眠流行(Hypnagogic pop),其歌曲和视觉效果受到了日本动画和漫画的直接启发。香港音乐厂牌Neoncity Records同样体现了这种潮流:它和国际音乐人签约合作——其中,便包括了来自墨西哥的マクロスMACROSS 82-99,他于2013年发行的专辑《SAILORWAVE》(致敬《美少女战士》)被认为是“只要操作得当,哈日族垃圾和蒸汽波美学的混合便会致命般迷人”的绝佳证明。[56](专辑封面见图3右半部分)

图3. 左半部分为Vektroid《Floral Shoppe》的专辑封面,其中,艺术家和专辑名均以日文写就;右半部分为マクロスMACROSS 82-99《SAILORWAVE》的专辑封面。

本章节的最后一个案例,是加拿大艺术家乔恩·拉夫曼(1981年生)的视频艺术作品《Still Life (Betamale)》【译注6】。《Still Life (Betamale)》最初作为其同名歌曲的MV,于2013年发布在YouTube上;歌曲作者为丹尼尔·洛帕廷(Daniel Lopatin | 1982年生),而他的艺名Oneohtrix Point Never要更为人所知。YouTube针对该视频采取了某些人看来“史无前例的举动”:它被YouTube封禁,随后被重新上传至视频分享网站Vimeo,但因其露骨的内容而再次被封。[57] 后来,拉夫曼在Vimeo上(第三次)补档成功,现在,该视频在两位艺术家的个人网站上也能正常播放。就内容而言,《Still Life (Betamale)》像是从互联网错误一侧摄录而成的意识流影像,其片段传达了一种以太般的怪异感。视频包括以下画面:穿着兽装和美少女布偶装(罗马音为animegao kigurumi,整套装备包括全身紧身衣、cosplay服装、以及动漫面具头壳)的业余扮演者、猥琐的(哈日族)癖好、八九十年代的日本黄油(eroge/成人色情游戏)截图和GIF图,等等。《Still Life (Betamale)》在时轴某一节点展现了一组异乎寻常般狂乱的色情图像大杂烩(collage),它们来自Gurochan,一个专攻血腥(gory)动漫风格、且通常为萝莉控(恋童[癖])类型插画的网络社区。拉夫曼解释道:和Gurochan的这种近距离接触,反映了他在网上冲浪直到令人作呕为止(ad nauseam)的过程——“影片高潮部分的某一时刻出现了海量的暴力恋物图像的累积。借此,我尝试表达在浏览深网[deep internet]并消费过多图片后的感官超负荷感。”[58]

恰好的是,《Still Life (Betamale)》中最先出现的图像之一,便是一个赤身裸体的肥胖白男的照片,它从屏幕正中的小矩形方块一直变大,向观众“靠近”,直至占据全部视野。该男子坐在一个贴满了日本动画海报的房间里(这一背景不禁使人恐惧地回想起摄于1989年的,连环“御宅”杀手宫崎勤狭窄卧室的著名照片),将两把[銃砲]对准自己的脑袋,同时戴着由两件童款比基尼胸罩和贴有可爱动漫美少女贴纸的粉色胖次组成的“面具”(见图4)。这张图像在短暂的、半下意识的闪回中再次出现:它夹在一系列极具攻击性的照片和CGI的大杂烩中,而叠加在照片上层的数字汗珠则顺着屏幕向下流动。这具令人作呕的、即将抵达爆炸极限的身躯突出强调了拉夫曼的《Still Life》所再现的贝塔男:他并非书生气的硅谷企业家,而是被阉割的Incel(involuntary celibate);他的怨恨、厌女和自怜一并构成了霸权式男性气概的有毒残渣,后者威胁着要从互联网边缘——它所栖居、酝酿的场所——蔓延开来。《Still Life (Betamale)》与Grimes和蒸汽波MV对哈日感(weeabooness)的酷化不同,它揭开了用户和爱好者赋权的遮羞布,即所谓的“贝塔革命”(Beta Uprising)。[59] 网络论坛中,那些类似4chan /r9k/版区或Reddit(红迪)r/ForeverAlone子版块的“惨白、白皮肤、愤怒的”[60]男性圈(manosphere)要么在幻想中复仇,要么在现实中——在北美发生的数起大规模(枪击)谋杀案和针对性的暴力事件都是由自我认同为Incel或信奉Incel意识形态的男子所犯下的;它们总共导致近50人死亡。[61] 有鉴于此,喜爱CGDCT动画的哈日族,似乎不再那么的“无害”。

图4. 《Still Life (Betamale)》中的“贝塔男”截图。

《Still Life (Betamale)》中还有一层可供分析的额外内容,但它并非拉夫曼本人有意创造出来的。作者就视频在4chan的/mu/版区匿名发起了一条讨论串,意在朝觐视频所致敬的爆红内容和冲击式影像的发源地“圣地麦加·4chan”。该讨论串最终被转换为长达43页的PDF文件并存档于拉夫曼的个人网站上;在文档中,4chan用户就视频做出了回复、并进行了深度讨论。然而,拉夫曼的“线上人类学/人类观察”自身竟成为了4chan用户厌恶和鄙视的对象。[62] 充满网络用语、表情包(image macro)、和反应图【译注7】的这份PDF文档甚至记录下了谙知拉夫曼所引用内容的用户对其艺术操守的疑问/质问;讨论串激起了许多讽刺评论,如:“这不过是Tumblr和福瑞答辩搅拌而成的更大一坨答辩罢了”、“惊了,原来您有Tumblr!恁做得好,做得好啊。福瑞真他妈的怪!日本黄片真他妈哈人!”(原话如此)。然而,最为愤慨的评论所针对的,是拉夫曼在未经许可且未标注引用来源的情况下便使用了超过30张源自Tumblr博客fmtownsmarty的日本电子游戏截图和GIF图的行为。同样来自Tumblr的一位用户在这场抗议中尤为直言不讳:TA指责拉夫曼延续了在他者文化内部(居高临下地)“体验生活”并偷挖这种文化,以获得供其通行传统艺术界的文化和社会资本的做法。[63] 如今,在拉夫曼的个人网站上,《Still Life (Betamale)》的页面里附上了一则告示,它“特别鸣谢”了拉夫曼所援引的诸多业余作品(包括fmtownsmarty、Gurochan,众多兽装和美少女布偶装扮演者,等等),但这则姗姗来迟且内容一点也不详细的告示似乎并没有平息对他的批评。

相比之下,拉夫曼在自己和艺术杂志的话语中皆宣称“自己坚决和那些构成了他作品的虚拟乐子人(reveller)保持团结一致,无论是‘第二人生’游戏(Second Life)的居民们,4chan上的‘福瑞控’,还是其他人。”[64] 和Grimes一样,他通过诉诸对“日本化的”亚文化的引用、并通过复制生产贴近千禧世代和年轻一代内心的特定产用方式,从而“扮演”成了他们的“自己人”。但是,4chan和Tumblr上反对专业艺术家挪用业余劳动成果的负面回应则暗示了登堂入室的艺术界和活生生的网络粪坑(gritty black alleys)之间的相互作用:它要更为复杂、且明显不那么和谐。事实上,尽管《Still Life (Betamale)》迎合了推崇用匿名/普遍性来对抗(冠名/特定的)知识产权的“复制粘贴”文化——而根据安德鲁·基恩(Andrew Keen)这样的“卢德派”作家所言,它“推波助澜地培养了年轻一代的知识偷窃狂”[65]——最后,它仍在切尔西的一家美术馆展出[66],而这则强调了艺术的历史认可过程中的特权和不平等现象(甚至在哈日风这样的微流派中也是如此)、以及这一过程在那些被排除在外的人群中激起的怨恨。

哈日族、性别、种族的交叉

本章节研究了数个案例,其中,哈日族与种族和文化的交叉是歌曲和MV的核心。比如说,命运·妮可·弗拉斯奎里(Destiny Nicole Frasqueri,1992年生)的另我人格,即纽约黎各裔(Nuyorican,纽约籍波多黎各裔)说唱歌手Princess Nokia。她经常在TA们【译注8】的歌曲中探讨后殖民和女性主义主题、并反映了TA们在布朗克斯区、西班牙哈莱姆区和纽约下东城的成长经历。[67] 只要在谷歌上简单一搜,便能找到各种宣传照,而无论是穿的像个哈莱姆假小子,还是在摆满Hello Kitty商品的橱窗前摇摆着紧身裙,TA们看起来都一样自在。在一张照片中,TA们抱着一只龙猫填充玩偶;另一张图中,戴着猫耳头箍的Princess Nokia向往地凝视着镜头;在别的照片中,穿着宝可梦衬衫的TA们咧嘴一笑,抽起了雪茄。“Dragons”一曲受《权力的游戏》角色丹妮莉丝·坦格利安启发,而它的MV在开头部分便出现了神龙(日本动漫《龙珠》系列作品中的魔龙)的画面(见图5左半部分)。借助令人回想起超8毫米胶片质感的业余影像、以及“丑陋”的特效与叠加效果,“Dragons”的MV展现了这样一幕:Princess Nokia和TA们的男友在电子游戏厅玩着像《街头霸王》(此时,镜头停留在穿着粉红色战袍的春丽身上)和《初音未来:歌姬计划》这样的经典日本电子游戏;这一幕中也同时穿插了日本动画和美国卡通的片段,例如《龙珠》和《宝可梦》,以及《X战警》和《魔法俏佳人》(Winx)。视频中,Princess Nokia的卧室里挂满了复古的二十世纪流行文化标志的海报和图画——其中包括《星球大战》、李小龙、美国漫画、和类似《侠盗猎车手》的电子游戏。在MV的某个片段中,这对情侣相拥在一起,在老式显像管电视上放着VHS磁带...在这怀旧的亲密空间中看起来并没有当今科技的一席之地。

图5. 左半部分为Princess Nokia的“Dragons”MV的截图(feat.《龙珠》中的神龙);右半部分为Princess Nokia专辑《Metallic Butterfly》的封面(feat.初音未来)。

Princess Nokia发行于2014年的出道专辑《Metallic Butterfly》的封面上出现了一张初音未来的同人图(见图5右半部分)。在无边无垠的都市夜景的衬托下,这位受人喜爱的、蓝绿色头发Vocaloid歌姬完美地体现了“高科技精灵音乐”[68]的美学,而根据Princess Nokia的说法,这种美学是本张专辑的基调(她似乎在告诉我们“网络无限宽广”,就像《攻壳机动队》中的草薙少佐那样)。“Cybiko”和本专辑的其他单曲大量援引了在日本流行文化影响下所创作出的欧美文化商品:像《黑客帝国》或《魔力女战士》(Æon Flux)这样“日本化”的电影和动画、类似《真人快打》的电子游戏,亦或,源自九十年代末和零零年代初的、充盈泡沫感的赛博-东方主义式Y2K美学。但是,考虑到最近有人指责Princess Nokia通过夸大或冒充非裔身份来“钓‘黑’鱼”【译注9】[69],TA们对文化模糊性和扮演(masquerade)的这种专注显得尤为讽刺。在任何情况下,对于Princess Nokia这样的艺术家而言,“日本酷的气息”不仅来自于千禧世代对日本流行文化的怀旧,而且还来自这种联想,即:卡哇伊和日本动画文化的全球化所生产出的依然是难以控制的杂交作品,乃至跨国界的“污染物”。学者克莉斯汀·矢野(Christine Yano)指出,即便是Hello Kitty这样看起来人畜无害的角色也会被人视为“坏榜样”,而它们的全球传播则滋生了“一大批声势浩大的诋毁者”。[70]

与此同时,像Josip On Deck(本名为约瑟普·奥帕拉-纳迪[Josip Opara-nadi],1993年生)和Hentai Dude(本名为科林·海恩斯[Colin Haynes],1994年生)这样的美国说唱歌手则在他们的歌曲和MV中肆无忌惮地引用着日本流行文化。如今,SoundCloud和Bandcamp上形成了各种音乐社群(music scene),而来自Nerdcore嘻哈和戏剧说唱这两种微流派的Josip On Deck和Hentai Dude都深度参与到了这种更为广泛的社群建设现象当中。Josip凭借“Anime Pu$$y”和“Mai Waifu”等歌曲在4chan上一举成名,在他的个人MV中,Josip一边抱着他最爱的等身抱枕(dakimakura),一边饶舌讲日本动画和游戏(见图6)。(遗憾的是,截至2021年6月,Josip的YouTube频道上的所有歌曲和MV都已被删除,除了“Anime Pu$$y”、和上传于2020年3月的新曲“Bape Store”之外。)尽管4chan是一个臭名昭著的、恶毒的种族主义轴心社区,但身为非裔的Josip从小便是该网站的忠实用户[71]。和许多人一样,Josip被“chan文化”的方方面面吸引,后者包括御宅族/游戏/网络迷因(例如LOLcats【译注10】)/激进骇客(hacktivist,例如Anonymous/匿名者)文化,等等。自从唐纳德·特朗普2016年当选美国总统以来,4chan已经和“政治不正确的”另类右翼与白人至上主义运动的网络巨魔捆绑在了一起。[72] 但这并不意味着诸类平台上从未出现过这种毒瘤(toxicity),例如,4chan和Reddit早已成为了Gamergate(玩家门)这样的骚扰活动的中心。[73]

事后诸葛亮一下:Josip的歌曲正是从4chan的政治不正确感中汲取了它的直率感,藉此,纵乐于后者最为荒谬难解的特征当中,而正如作家乔安妮·麦克尼尔(Joanne McNeil)所言,这种所谓“从匿名(anon)到另类右翼”的转变使得这种直率感愈加复杂。[74] Josip所唱的出格台词如下:

Damn I love mai waifu, she ain’t nothing like you

操 我他妈爱我老婆 你和她就是云泥之别

She don’t bitch and nag me all the time up on her cycle [menstrual]

来事儿(月经)时她绝不犯贱 更不瞎鸡巴逼逼咧咧

Damn I love mai waifu, her figure is so curvy

干 我爱死我老婆力 她的曲线是真鸡儿赞

When you stand by mai waifu I can tell that you’re not worthy. [75]

一跟她并排站在一起 小爷就看出 您不配

图6. Josip On Deck在歌曲“Senpai Gon Notice You”(2014)的MV中抱着一个等身抱枕;抱枕上的人物为日本动画《幸运星》中的泉此方。

同人圈俚语“Waifu”(老婆)——即英文“wife”一词的日语音译——展现了男性对萌系角色的占有欲,而这种御宅族的厌女则和匪帮说唱中的有所重叠。事实上,上文所摘引的“Mai Waifu”的歌词将“同时非人化和超人化的、抽象且无生命的”动漫老婆和现实中的女性直接对立了起来;比起身带恼人的生理机能和官能机制【译注11】的女人,二次元老婆要明显更具优势。[76] 在“Anime Pu$$y”一曲中,Josip恬不知耻地宣称“俺希望世上所有女孩都是纸片人”。[77] 这种从真实“pussy”(女性外阴)到寂寞阿宅幻想爱上虚构女友的滑坡在嘲讽荒唐的、“日本化”的哈日族的同时,也讽刺了匪帮说唱中典型的“有关性、毒品和毁灭的高谈阔论”。[78]

另一个有趣的方面是:Josip才是本文提及的所有艺术家中最符合哈日族定义的,一目了然——他是一位名副其实的Weeaboo,而不是其他哈日风案例中的哈日族“变种”。Josip的歌曲和视频中充斥着网络用语和无端的日语表达(例如Konnichiwa/こんにちは/你好、卡哇伊、斯国一、萌、dokidoki/ドキドキ/心动,并自称Josip-san/Josip桑...),以至于那些对网络同人圈的日文/深网用语不大了解的观众可能会感到彻底的无所适从。Josip也意识到了哈日族在社会中受人嫌弃或不被认可的地位(歌词:“俺只想看点进巨、逛个漫展/为啥大伙都劝我别玩耍”)。尽管如此,Josip是一位自称“御宅之神”(Otaku Kami-Sama)的艺术家,他强行建立了一种“本真”或“理想”的(日本)身份认同,从而颠覆了某些人所说的日本动画及其同人圈中的“种族问题”。[79] 比如说,这种“种族问题”在常规化(normalized)的“Cosplay文化中的种族主义”中尤为明显:它歧视像Josip这样的非裔爱好者——后者极难落入先入为主的民族-种族正统性观念当中,而在这种观念下,只有在cosplay成动漫角色时体现了刻板印象型的日本性或“默认般”的白人性(whiteness)的coser才是可以被接受的。[80] 在Josip的另一部杰作“I’m Japanese”中,他甚至唱道:“小爷照镜子时/瞅着一个霓哥(Japanese nigga)”、“俺只操自个种族的妞儿(系远东妞捏)”。[81] 为了挑衅他人和呈演冲击式幽默,而挥舞“跨文化乃至跨种族和跨民族的身份禁忌”这具大棒的Josip“污染了”嘻哈音乐如实体现都市黑人文化的操守。

不过,Josip On Deck并不是唯一一个在哈日族境况中求索“底层幽默”的艺术家。[82] 另一位在一零年代中期发迹于SoundCloud说唱社群的美国唱作人Doja Cat(本名为阿玛拉·德拉米尼 [Amala Dlamini],1995年生)在其作品中探讨了萌感、过度性化(hypersexuality)、以及淫秽之间的交叉。这位美国犹太母亲和南非父亲的混血女儿凭借爆红歌曲暨MV“Mooo!”(2018)成为了人们关注的焦点。[83] “Mooo!”是一部“烂到极致便是真”的DIY神作,内含低劣的绿幕效果和偶尔悬停在影像上方的鼠标指针——这使得一位YouTube用户评论道:“这不可能不是在凌晨三点做出来的”。[84] Doja Cat在视频中跳着舞、吃着汉堡和薯条、喝着奶昔,同时,交换穿着凸显胸部的奶牛斑点服和性感的牧场风牛仔短裤&比基尼。她唱着“婊子,我是头牛”和“我不是猫,我不喵叫”之类的歌词。混在歌词中的性别化的贬义动物称谓(bitch/母狗、奶牛、猫儿)在使人迷惑不安的同时,亦呼应了歌曲后面的一系列性暗示、以及女性和牛肉部位与乳制品的相提并论(歌词:“有牛奶吗,婊子?有牛肉没?有牛排吗,骚逼?有奶酪没?”【译注12】、“我是A级的丰乳肥臀,婊子,才不是什么瘦竹竿”,等等...)。与此同时,视频背景中滚动展示着一系列网络影像,其中包括卡哇伊风格的牛奶和冰淇淋包装盒、可爱的奶酪汉堡包和牧场风光的像素动画艺术图、实拍奶牛镜头、有趣的奶牛广告、奶牛相关的搞笑视频,以及最为突出的,穿着三点式比基尼的巨乳乳摇动画GIF图(见图7)【译注13】。

图7. Doja Cat “Mooo!”MV的截图,背景为动画乳摇GIF。

尽管表面如此,但Doja Cat同时使用的性相关的、性别歧视的、污秽下流的(原文为scatological,在本视频语境中,重复消费荧屏上的奶牛副产品尤其令人作呕)、荒谬的幽默(的内涵)却是极为复杂的。她通过文字及视觉上的双关,在两种形式的“动物性的非人化”之间建立起了一种令人不快但意味深长的联系。[85] 一方面,过度性化的无耻荡妇(Jezebel)的刻板印象,即“被高度性化且价值仅限于‘性’的,迷人又妖娆的非裔美国妇女”,是对黑人的压迫历史的一部分。[86] 然而,取其精华,去其糟粕后的这种意象经常被嘻哈乐和黑人灵歌使用,而Doja Cat则通过说唱和拖长类似“smooth”和“mood”的单词中的“mooo”音的方式唤起了后者的音乐传统。另一方面,“‘动物化’的御宅族”[87]对动画胸部的性欲——这里借用了东浩纪在《动物化的后现代》一书中对御宅族的后现代萎靡不振的著名论述——则被囊括在MV背景里重复循环播放的GIF图内跳动的“超夸张奶子”(gag boobs)[88]中。这种并置暗示了一种连续性:无论是在历史实在(historical reality)中,还是在御宅族“没有深度的”后历史幻想范畴当中,女性仍然被系统性地“简化为她的身体,并且仅被视作为他者的愉悦而生的工具”。[89] 这种连续性,再加上视频的DIY故障美学和淫秽的歌词,表明了一种抵制人类发展和技术进步目的论的创作立场。尽管如此,任何将“Mooo!”解读成一部“直接表达了文明的祛魅”的作品的尝试,都会被它散发出的纯粹的戏谑感反驳。

Doja Cat近期(2019年)发布的MV“Like That”同样在内化的男性凝视(可以这么认为),与开玩笑似的揭示、批判、和重新诠释(reclaim)美国和日本文化产业中存在问题的性别和种族因素之间走着钢丝。“Like That”的DIY感相比“Mooo!”的要更不明显,但它依然和千禧青年的数字用语之间维系着显而易见的联系。例如,视频中出现了爱心和星光的颜文字、幽默的印章图案、梦幻朦胧的滤镜、以及最重要的:一段类似Flash动画的业余动画,其中,扮演成水手战士的Doja Cat在魔法背景前变身(见图8)。动画人物的服装与“摄像机”的视角聚焦在她的裸臀和过分暴露的开胸内衣上,从而使得这段精心编排的变身片段的性暗示感愈加明显。这样一来,Doja Cat在变身片段的“挪用和再挪用的循环”——从它们在《魔法使莎莉》这样的日本动画中的粗糙起源,到它们在永井豪的少年向作品《甜心战士》中的景观化和色情化,再到它们借《美少女战士》中的少女-力量型动作女主角回归女性群体(的生产-消费视域)——之上添加了另一层含义。如今,重新融合了Doja Cat的“色情卡哇伊”(ero-kawaii)美学的魔法少女被进一步卷入了嘻哈女性主义中的复杂的性别、种族、和阶级协商(negotiation)中。

图8. “Like That”的截图;其中,Doja Cat像月野兔一样摆着姿势。

本文中,Doja Cat和其他爆红艺术家的案例表明:在这个充斥着各种亚文化和微流派的全球媒介空间中(原文为mediasphere,而注意力是它的硬通货),哈日风呈现了一种与众不同且令人印象深刻的,对千禧世代和年轻一辈谙知的引用内容、用语和行为的再现,甚至在他们对后者持否定态度时亦是如此。通过言说、创作和表演那些若不借助日本动画、漫画和电子游戏影像——以及它们在英文网络世界中的衍生物(这至关重要)——就无法表达的故事,哈日族便可以和那些所谓“在同一条贼船”上的观众沟通交流。他们在此过程中建立了一套新标准,要求观众具备不同程度的亚文化知识来理解哈日程度不同的作品——从温柔随和的“日本化”作品(Grimes),到浓度过高的作品(Josip on Deck),等等。矛盾的是,在“拉夫曼线上人类学作品的登堂入室”等现象的推波助澜下,哈日感的酷化终究复辟了某些等级制度,但这主要是因为通过援引日本流行文化从而作为爱好者相互认同并凝聚在一起的行为已经成为了哈日风体验的关键组成部分:你要么跟他们一起“萌就完事了”,要么因为无法感同身受而自愿/被迫滚出他们的小圈子。

和民族-种族意义上的“正统”御宅族不同,“想要成为日本人”的人必然不是日本人,所以,本文中的艺术家共享了某种(狡猾,并且有时颇具争议的)负面身份,后者既与媒介化的“日本”密不可分,又可以被置于任何境地之中——除了“真正的”日本。因此,作为在日本流行文化熏陶中长大成人的全球消费者,这些艺术家在操演着自身状况的自然感和真诚感的同时,也流露出了一种“有事不对劲”的意识。用茱莉亚·克莉斯蒂娃的话说,如果哈日族体现了“不再来自外部,而是来自内部的威胁”,那么“日本”便成为了某种幽灵,缠绕(haunt)在西方现代性那神话般的纯洁当中。[91] 哈日风的全部意义,在于享受、改变和玩弄作为千禧世代幻景(phantasmagoria)之臆造物的、日本流行文化的“扭曲”,而哈日风所应用的创作方式则反映了和环境、性别、文化和种族相关的更广泛的社会变化,并在前者与后者的交叉中相互建立起了关联。哈日风对所谓的“西方艺术和文化领域”提出了质疑,甚至打破了这一概念本身,从而扰乱了混合主义(hybridism)和国际主义那令人心安理得的话语,后者往往围绕着文化“软实力”的传播,无论是在现实世界、还是在数字世界中。

致谢

作者要感谢Mechademia期刊的匿名审稿人,他们仔细阅读了作者的文章、并给出了精辟的评论及修改意见。作者还要特别感谢史蒂维·苏安(Stevie Suan),他花时间帮作者改进了初稿,并且,他宝贵的反馈意见使得终稿的质量有了显著提升。本作品受葡萄牙科学与技术基金会(FCT Portugal)赞助,项目批准号为SFRH/ BD/ 89695/ 2012。

译注

1. 原文为“anthem”,在本文的语境中可将“Genesis”一曲理解为赞颂日本流行文化的颂歌。

2. 原文为“black lipstick”,但MV相应片段中的口红色号为红色,此处疑为作者笔误。

3. 原文为“cute culture”,在译文中,译者将“cute”和“moe”灵活翻译为“萌”或“可爱”。

4. 延伸阅读(或许):柄谷行人《日本现代文学的起源》第一章 <风景之发现>

5. 译者会在所有翻译文本中一律将“Anime”严格地译为“日本动画”,但在个别语境中(如此处)亦需要将“Anime”灵活译作“动漫”。

6. 西方互联网语境中的Beta male/贝塔男/β男,是指缺乏阳刚之气并拥有女性气质的男人,他们经常以被动攻击方式面对困难或冲突(Urban Dictionary);他们不像其他男人[如Alpha male]那样成功或强大(Cambridge Dictionary)。

7. 原文为“reaction pic”,其意为:用于描述某人对某事的感觉的图片(一般而言,它描绘了某人的面部表情)。它可以是迷因...通常如此——Urban Dictionary。实践是检验真理的唯一标准,译者为大家准备了一则范例。E.g., 怎么看中华人民共和国COVID-19管控对新加坡经济发展的影响?如图(利好新加坡):

8. 如前文所述,Princess Nokia的性别认同为非常规性别,而TA所使用的人称代词为:she/her和they/them | 关注代名词政治,关注International Pronouns Day谢谢喵——译者

9. 原文为“blackfishing”,指:不是非裔的(欧美白)人利用化妆和发型使自己的肤色更黑、并看起来更像非裔或非裔混血儿(BBC),它往往和扮黑脸(blackface)有着同等的种族歧视/文化挪用色彩。另请参见:https://www.health.com/mind-body/what-is-blackfishing

10. 指:在一幅家猫的照片上加上了字幕的图片;图中的字幕通常会以特异的方式串出,或是以不符合文法和幽默的方式书写(Wikipedia)。如图:

11. 原文为“biological and organic functions”。例如:女性的月经(biological),和所谓的女性“歇斯底里”(organic)。

12. 性俚语(辱了,请小心使用,保持尊重):milk/牛奶=奶子,beef/肉=女阴,steak/牛排=>参见eating steak(性交)、steak and shake(骑乘位)、Steak and Blowjob/Pussy Day(女人为男人做牛排吃,然后为他口交/性交)...,cheese/奶酪=白色的阴道分泌物(clitoral smegma)。

13. 出自《梦物语》(ゆめりあ,2004)第4集19分37秒。

附录

1. 亚历克斯·巴雷多(Álex Barredo):<跌落神坛的汤不热>(Tumblr Is Tumbling),Hacker Noon,2017年11月25日,https://hackernoon.com/tumblr-is-tumbling-d6deb3bb831e

2. 劳拉·哈德森(Laura Hudson):<受埃隆·马斯克鼓励的Grimes正将她的名字改成光速符号>(Grimes Is Changing Her Name to the Symbol for the Speed of Light, Encouraged by Elon Musk),The Verge,2018年5月19日,https://www.theverge.com/2018/5/19/17372526/grimes-c-boucher-name-change-elon-musk

3. 卡丽·巴妲(Carrie Battan):<采访Grimes:Genesis>,Pitchfork,2012年8月27日,提问“There’s a Lot Going on Here”(MV里发生了许多事情),https://pitchfork.com/features/directors-cut/8929-grimes/

4. Grimes:《Genesis》

5. 道格拉斯·麦格雷(Douglas McGray):<日本的国民‘酷’总值>(Japan’s Gross National Cool),《外交政策》杂志,2009年11月11日,http://foreignpolicy.com/2009/11/11/japans-gross-national-cool/

6. 安迪·格林尼(Andy Greene):<全年代排名前十的‘一片歌手’:滚石读者评选>(Top 10 One-Hit Wonders of All Time: Rolling Stone Readers Pick),《滚石》杂志,2011年5月4日,第二段,https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-lists/rolling-stone-readers-pick-the-top-10-one-hit-wonders-of-all-time-14391/

7. 詹妮弗·萨诺-弗兰契尼(Jennifer Sano-Franchini):<发出亚洲/美国的声音:亚洲/美国的声音修辞学、多模态东方主义、和数字作曲>(Sounding Asian/America: Asian/American Sonic Rhetorics, Multimodal Orientalism, and Digital Composition),《Enculturation》,2018年12月18日,第一段“Aural Stereotyping”(听觉的刻板印象化),http://enculturation.net/sounding-Asian-America

8. 杰森·理查兹(Jason Richards),<日本对Grimes的影响越来越深>(Japan’s Influence on Grimes Grows Deeper),《日本时报》,2013年3月21日,第一和第四段,https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2013/03/21/music/japans-influence-on-grimes-grows-deeper/

9. <哈日族>,Know Your Meme,第1-2段,https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/weeaboo,2021年1月29日读取

10. 参见<哈日族>第3-4段

11. 参见<哈日族>第5段;可以在此阅读最初的连环漫画:https://pbfcomics.com/comics/weeaboo/

12. 塞莉·奥尼尔-哈特(Celie O’Neil-Hart)、霍华德·布卢门施泰因(Howard Blumenstein):<为何YouTube网红要比传统明星更有影响力>(Why YouTube Stars Are More Influential Than Traditional Celebrities),Think with Google,2016年7月,https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/marketing-strategies/video/youtube-stars-influence/

13. 亨利·詹金斯、萨姆·福特(Sam Ford)、约书亚·格林(Joshua Green):《可传播的媒介:在联网文化中创造价值和意义》(Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture),纽约:纽约大学出版社,2013年

14. 罗兰·凯尔茨:《日治美利坚:日本流行文化是如何入侵美国的》(Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the U.S.),纽约:Palgrave Macmillan出版社,2007年

15. 克莉斯汀·矢野:<Kitty的倒错:日本萌的跨国越轨>(Flipping Kitty: Transnational Transgressions of Japanese Cute),《Medi@sia:语境内外的全球媒介/中介化》(Medi@sia: Global Media/tion in and out of Context),托德·约瑟夫·迈尔斯·霍尔登(Todd Joseph Miles Holden)、蒂莫西·J·斯克雷瑟(Timothy J. Scrase)编,伦敦:Taylor & Francis出版社,2006年

16. 克里斯托弗·施密特(Christopher Schmidt):《秽物的诗学:斯泰因、阿什贝利、斯凯勒和戈德史密斯文本中的酷儿剩余》(The Poetics of Waste: Queer Excess in Stein, Ashbery, Schuyler, and Goldsmith),纽约:Palgrave Macmillan出版社,2014年,页4-5

17. 米歇尔·鲍文斯(Michel Bauwens):<产用革命:杰出的全新篇章>(The Produsage Revolution: A Stellar New Book),P2P Foundation,2007年11月15日,https://blog.p2pfoundation.net/the-produsage-revolution-a-stellar-new-book/2007/11/15

18. 大卫·贝瑞(David Berry)、迈克尔·迪特(Michael Dieter)编:《后数字美学:艺术、计算和设计》,纽约:Palgrave Macmillan,2015年,页21-22

19. <如何避免成为哈日族>,WikiHow,https://www.wikihow.com/Avoid-Becoming-a-Weeaboo,2021年2月12日读取

20. 托马斯·拉马尔:<酷、恶心、可爱:御宅族的虚构、话语和政策>(Cool, Creepy, Moe: Otaku Fictions, Discourses, and Policies),《Diversité Urbaine》,第13卷、第1期(2013年),页133-34,https://doi.org/10.7202/1024714ar

21. 凯西·布里恩扎:<‘日本漫画不是披萨’:斯韦特兰娜·赫马科娃作品‘Dramacon’中,民族-种族正统性的操演、以及美国的日本动漫同人圈政治>(‘Manga Is Not Pizza’: The Performance of Ethno-Racial Authenticity and the Politics of American Anime and Manga Fandom in Svetlana Chmakova’s Dramacon),《全球日本漫画:没有日本的‘日本’漫画?》(Global Manga: “Japanese” Comics without Japan?),凯西·布里恩扎编,伦敦:Routledge出版社,2015年,页95-113

22. Fled From Nowhere:<Weeb>,Urban Dictionary,2017年5月22日,第1段,https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=weeb

23. 约翰·奥普利格(John Oppliger):<问约翰吧:为什么美国人认为萌正在杀死日本动画?>(Ask John: Why Do Americans Think Moe Is Killing Anime?),AnimeNation Anime News Blog,https://www.animenation.net/blog/ask-john-why-do-americans-think-moe-is-killing-anime/,2021年1月29日读取

24. 帕特里克·W·加尔布雷斯:<‘御宅族’研究和对失败男性的焦虑>(‘Otaku’ Research and Anxiety About Failed Men),《当代日本御宅族讨论:历史视角与新视野》(Debating Otaku in Contemporary Japan: Historical Perspectives and New Horizons),帕特里克·W·加尔布雷斯、谭发甘(Thiam Huat Kam)、比约恩-奥勒·卡姆(Björn-Ole Kamm)编,伦敦:Bloomsbury Academic出版社,2015年,页21

25. <为什么日本动画社区憎恨腐女子?>(Why Does the Anime Community Show Hate towards Fujoshis?),MyAnimeList.net,https://myanimelist.net/forum/?topicid=1729866,2021年4月28日读取

26. 史蒂芬妮·奥姆(Stephanie Orme):<女性气质与同人圈:女性美国漫画爱好者的双重污名化>(Femininity and Fandom: The Dual-Stigmatisation of Female Comic Book Fans),《Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics》,第7卷、第4期(2016年10月1日),页403-416,https://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2016.1219958

27. 参见贝瑞、迪特,《后数字美学》,页21-22

28. 与田登美子(Tomiko Yoda):<通向千禧日本的道路图>(A Roadmap to Millenial Japan),《日本后的日本:从衰退的九十年代到现在的,社会和文化生活》(Japan After Japan: Social and Cultural Life from the Recessionary 1990s to the Present),与田登美子、哈利·哈罗图尼安(Harry Harootunian)编,德罕:杜克大学出版社,2006年,页46

29. 参见贝瑞、迪特,《后数字美学》,页20

30. 参见贝瑞、迪特,《后数字美学》,页21-22

31. 德拉甘·艾斯朋谢尔德(Dragan Espenschied)、奥莉亚·莉琳娜(Olia Lialina):《数字民俗》(Digital Folklore),斯图加特:Merz & Solitude出版社,2009年

32. 内奥米·弗莱(Naomi Fry):<埃隆·马斯克和Grimes的麻烦事>(The Trouble with Elon Musk and Grimes),《纽约客》,2018年5月10日,https://www.newyorker.com/culture/annals-of-appearances/the-trouble-with-elon-musk-and-grimes;凯尔·姆恩泽雷德(Kyle Munzenrieder):<Grimes解释她是如何做一个与亿万富翁约会的伯尼·桑德斯支持者的>(Grimes Explains How She’s a Bernie Supporter Who Dates a Billionaire),《W Magazine》,2020年3月5日,https://www.wmagazine.com/story/grimes-bernie-sanders-elon-musk

33. <Claire de Lune on Twitter>,Twitter,https://twitter.com/Grimezsz/status/1108202117813043200,2021年1月22日读取

34. 斋藤环:《战斗美少女的精神分析》,基斯·文森特(Keith Vincent)、唐·劳森(Dawn Lawson)英译,明尼阿波利斯:明尼苏达大学出版社,2011年

35. kyky:<‘Grimes——Delete Forever (Official Video)’评论区的留言>,YouTube,2020年7月,https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gvzC8MmC850

36. Grimes:《MY NAME IS DARK (LYRIC_VIDEO) (NOT Thee OFFICIAL VIDEOOO, Just a Cute Vibe) Xxo》,YouTube,2019年,https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fq1fW-jIRms&feature=emb_title

37. 威廉·吉布森:<Grimes新视频的YouTube评论区好像有点困惑...解释一下,我的小说‘Idoru’献给的是我和我妻子的女儿克莱尔,而不是Grimes。>,Twitter,https://twitter.com/GreatDismal/status/1233621922442645504,2021年1月29日读取

38. Grimes:《Grimes——Idoru (Slightly Shorter Version)》,YouTube,2020年3月,https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f8Pn5tOM92c

39. bunny !!!:<‘Grimes——Idoru (Slightly Shorter Version)’评论区的留言>,YouTube,2020年3月,https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f8Pn5tOM92c

40. erinspitfire:<‘Grimes——Idoru (Slightly Longer Version)’评论区的留言>,YouTube,2020年3月,https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oCrhTU9HkVQ

41. 尼克·道格拉斯(Nick Douglas):<它看起来就该像屎一样:互联网丑陋美学>(It’s Supposed to Look Like Shit: The Internet Ugly Aesthetic),《Journal of Visual Culture》,第13卷、第3期(2014年12月1日),页314-339,https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412914544516

42. Lizzie Wilson:<‘MY NAME IS DARK (LYRIC_VIDEO) (NOT Thee OFFICIAL VIDEOOO, Just a Cute Vibe) Xxo’评论区的留言>,YouTube,2020年5月,https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fq1fW-jIRms&lc=Ugyocnbzsyoxbv2SnEh4AaABAg

43. Grimes:《Grimes — You’ll Miss Me When I’m Not Around (Chroma Green Video)》,YouTube,2020年,https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_IHaCyX6-Xo

44. 西安妮·恩盖(Sianne Ngai):《丑陋的情感》(Ugly Feelings),剑桥(麻萨诸塞州):哈佛大学出版社,2007年,页6

45. 马克·费雪:《怪异与怪异》(The Weird and the Eerie),伦敦:Repeater出版社,2017年

46. 艾莉西亚·埃莱尔、凯特·杜宾:<少女的Tumblr美学>,Hyperallergic,2013年3月1日,https://web.archive.org/web/20180124083049/https://hyperallergic.com/66038/the-teen-girl-tumblr-aesthetic/

47. 罗伯特·阿尔布里顿(Robert Allbritton):《政治经济学中的辩证法与解构》(Dialectics and Deconstruction in Political Economy),贝辛斯托克:Palgrave Macmillan出版社,2001年,页156

48. 罗莎琳·E·克劳斯、伊夫-阿兰·博瓦:《无定形:使用指南》,纽约:Zone Books出版社,1997年,页118

49. 西蒙·雷诺兹:《复古狂热:流行文化对自身过去的痴迷》(Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past),伦敦:Faber & Faber出版社,2012年,页xiii-xiv

50. 本·史密斯(Ben Smith):<从未发生的明日:蒸汽波中的日本图像学>(The Tomorrow That Never Was: Japanese Iconography in Vaporwave),Neon Music,2017年10月15日,第四段,https://neonmusic.co.uk/japanese-iconogrpahy

51. 肯尼思·霍夫(Kenneth Hough)等人:《技术-东方主义:在虚构小说、历史和媒介中想象亚洲》(Techno-Orientalism: Imagining Asia in Speculative Fiction, History, and Media),大卫·S·罗(David S. Roh)、贝琪·黄(Betsy Huang)、格蕾塔·A·牛(Greta A. Niu)编,新布朗斯维克市(新泽西州):罗格斯大学出版社,2015年

52. 岩渕功一:<共犯的异国情调:日本和它的他者>,《Continuum》,第8卷、第2期(1994年1月1日),页49-82,https://doi.org/10.1080/10304319409365669

53. 参见与田登美子,<通向千禧日本的道路图>,页34

54. 西蒙·钱德勒(Simon Chandler):<逃避现实:蒸汽波的图像学>(Escaping Reality: The Iconography of Vaporwave),Bandcamp Daily (blog),2016年9月16日,https://daily.bandcamp.com/2016/09/16/vaporwave-iconography-column/

55. <Mukokuseki>(无国籍),http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/Mukokuseki,2017年11月15日读取;岩渕功一:《重新定位全球化的中心:流行文化与日本跨国主义》(Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism),德罕:杜克大学出版社,2002年,页28

56. EntryIncomplete:<‘マクロスMACROSS 82-99 — Sailorwave’评论区的留言>,Alum of The Year,2021年,https://www.albumoftheyear.org/album/55428-macross-82-99-sailorwave.php

57. 杰米·奥特萨(Jamie Otsa):< Oneohtrix Point Never的‘Still Life Betamale’NSFW音乐视频被YouTube封禁>,《Glasswerk Magazine》,2013年9月25日,第1段,http://glasswerk.co.uk/magazine/article/19289/Oneohtrix+Point+Never+NSFW+Still+Life++Betamale++Video+Banned+From+Youtube/

58. 乔恩·拉夫曼:<史蒂芬·弗勒泽采访拉夫曼>(Jon Rafman, interview by Stephen Froese),《Pin-Up: Magazine for Architectural Entertainment》,秋-冬季刊(2013年),页88

59. 凯特琳·杜威(Caitlin Dewey):<Incels、4chan和贝塔革命:理解互联网上最令人反感的亚文化之一>(Incels, 4chan and the Beta Uprising: Making Sense of One of the Internet’s Most-Reviled Subcultures),《华盛顿邮报》,2015年10月7日,第17段,https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-intersect/wp/2015/10/07/incels-4chan-and-the-beta-uprising-making-sense-of-one-of-the-internets-most-reviled-subcultures/

60. 张哲熙(Gary Zhexy Zhang):<乔恩·拉夫曼的线上人类学>(The Online Anthropologie of Jon Rafman),《Frieze: Contemporary Art and Culture》,2016年2月,页95

61. 布鲁斯·霍夫曼(Bruce Hoffman)、雅各布·瓦雷(Jacob Ware)、埃兹拉·夏皮洛(Ezra Shapiro):<评估Incel暴力的威胁>(Assessing the Threat of Incel Violence),《Studies in Conflict & Terrorism》,第43卷、第7期(2020年4月19日),页565-573

62. 参见张哲熙,<乔恩·拉夫曼的线上人类学>

63. ulan-bator:<评论>,Tumblr,2013年10月29日,http://ulan-bator.tumblr.com/post/62549448638/vimeo-com75402303

64. 参见张哲熙,<乔恩·拉夫曼的线上人类学>,页92

65. 安德鲁·基恩:《网民的狂欢:关于互联网弊端的反思》(The Cult of the Amateur: How Blogs, MySpace, YouTube, and the Rest of Today’s User-Generated Media Are Destroying Our Economy, Our Culture, and Our Values),纽约:Doubleday出版社,2008年,页23

66. 玛莉亚姆·纳兹里普尔(Mariam Naziripour):<福瑞是怎样出现在切尔西的一家美术馆的>(How Furries Wound up in an Art Gallery in Chelsea),Kill Screen,2013年12月9日,https://killscreen.com/articles/furries-betamale-and-future-stealing-art-online/

67. 切尔西·坎贝尔(Chelsea Campbell):<Princess Nokia真的作为纽约市的多维度女王出现在外了!>(Princess Nokia Is Really out Here as the Multidimensional Queen of NYC),KultureHub,2017年9月8日,第4段,https://kulturehub.com/princess-nokia-queen-nyc/

68. <Princess Nokia: ‘Cybiko’>,(The) Absolute,2014年,第1段,http://theabsolutemag.com/14243/music/princess-nokia-cybiko/

69. <谈谈她钓黑鱼>(On Her Blackfishing),Tumblr,https://wickedghastly.tumblr.com/post/630474053257396224/where-can-i-find-info-on-princess-nokia,2021年2月11日读取

70. 参见矢野,<Kitty的倒错>,页217

71. 费尔南多·阿方索(Fernando Alfonso):<介绍Josip on Deck,统治4chan的日本动画痴兼说唱歌手>(Introducing Josip on Deck, the Anime-Obsessed Rapper Who Rules 4chan),The Daily Dot,2013年9月9日,第3-6段,https://www.dailydot.com/upstream/josip-on-deck-4chan-otaku-anime-rapper/

72. 乔安妮·麦克尼尔:<从匿名到另类右翼:4chan上的危险渔夫>(From Anon to Alt-Right: The Dangerous Tricksters of 4chan),Literary Hub,2020年3月2日,第1-2段,https://lithub.com/from-anon-to-alt-right-the-dangerous-tricksters-of-4chan/

73. 凯西·约翰斯顿(Casey Johnston):<[Chat Logs]展现了4chan用户是如何创造#GamerGate争议的>(Chat Logs Show How 4chan Users Created #GamerGate Controversy),Ars Technica,2014年9月9日,https://arstechnica.com/gaming/2014/09/new-chat-logs-show-how-4chan-users-pushed-gamergate-into-the-national-spotlight/

74. 参见麦克尼尔,<从匿名到另类右翼>

75. Josip on Deck:《Josip On Deck — Mai Waifu (Music Video)》,YouTube,2012年,https://web.archive.org/web/20150404111205/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=djI6nc9EVMM

76. 马可·佩利特里(Marco Pellitteri):《龙和耀眼的光芒:日本想象力的模型、策略与身份——一个欧洲视角》(The Dragon and the Dazzle: Models, Strategies, and Identities of Japanese Imagination: A European Perspective),伊斯特利(英国):John Libbey出版社,2011年,页80

77. Josip on Deck:《Josip On Deck — Anime Pu$$y Ft. Killa Karisma (Music Video)》,YouTube,2019年,https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qe3c2XGnJw4

78. 贾巴里·阿西姆(Jabari Asim):《N Word:谁可以说它,谁不应该说它,以及为什么》(The N Word: Who Can Say It, Who Shouldn’t, and Why),波士顿:Houghton Mifflin Harcourt出版社,2007年,页229

79. 乔什·杜桑-施特劳斯(Josh Toussaint-Strauss)、乔瑟夫·皮尔斯·瑞恩·巴克斯特(Joseph Pierce Ryan Baxter)、保罗·鲍伊德(Paul Boyd):<视频——日本动漫有种族问题,让我们看看非裔爱好者是怎么解决它的>(Anime Has a Race Problem, Here’s How Black Fans Are Fixing It — Video),《卫报》,2020年10月1日,https://www.theguardian.com/culture/video/2020/oct/01/anime-has-a-race-problem-heres-how-black-fans-are-fixing-it-video

80. 塔琳恩·克尔(Talynn Kel):<你的同人圈是种族主义的,你也是>(Your Fandom Is Racist and So Are You),The Establishment,2017年12月8日,https://theestablishment.co/your-fandom-is-racist-and -so-are-you-638c5200b15b/

81. Josip on Deck:《Josip On Deck — I’m Japanese (Music Video)》,YouTube,2014年,https://web.archive.org/web/20160731000402/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jgE4nV5tirQ

82. 参见恩盖,《丑陋的情感》,页271

83. 朱莉安娜·帕齐(Juliana Pache):<Doja Cat会做她想做的任何事>(Doja Cat Will Do Whatever She Wants),The FADER,第4段,https://www.thefader.com/2019/09/19/doja-cat-amala-hot-pink-interview,2021年1月23日读取

84. cereals:<‘Doja Cat — ‘Mooo!’ (Official Video)’评论区的留言>,YouTube,2020年,https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mXnJqYwebF8

85. 乔尔·R·安德森(Joel R. Anderson)、爱丽丝·霍兰德(Elise Holland),柯特妮·海尔德雷思(Courtney Heldreth)、斯科特·P·约翰逊(Scott P. Johnson):<回到无耻荡妇的刻板印象:被针对的族裔对性物化的影响>(Revisiting the Jezebel Stereotype: The Impact of Target Race on Sexual Objectification),《Psychology of Women Quarterly》,第42卷、第4期(2018年12月1日),页462,https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684318791543

86. 参见安德森、霍兰德、海尔德雷思、斯科特,<回到无耻荡妇的刻板印象>,页463

87. 乔纳森·E·亚伯(Jonathan E. Abel):<译者序>,《动物化的后现代:御宅族如何影响日本社会》,明尼阿波利斯:明尼苏达大学出版社,2009年,页xvi

88. <Gag Boobs>,TV Tropes,https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/GagBoobs,2021年4月29日读取

89. 参见安德森、霍兰德、海尔德雷思、斯科特,<回到无耻荡妇的刻板印象>,页461

90. 阿刻亚·A·F·伯纳德(Akeia A. F. Benard):<父权制资本主义下,黑人女性身体的殖民化:从女性主义与人权角度来看>(Colonizing Black Female Bodies Within Patriarchal Capitalism: Feminist and Human Rights Perspectives),《Sexualization, Media, & Society》,第2卷、第4期(2016年12月1日),页7-9,https://doi.org/10.1177/2374623816680622

91. 茱莉亚·克莉斯蒂娃:《恐怖的权力:论卑贱》(Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection),里昂·S·鲁迪耶兹(Leon S. Roudiez)英译,纽约:哥伦比亚大学出版社,1982年,页114

作者介绍

截止发稿时,安娜·玛蒂尔德·索萨是一位在里斯本定居和工作的视觉艺术家兼学者。她持有里斯本大学艺术学院(FBAUL)颁发的视觉艺术-绘画博士学位,并在艺术研究中心(CIEBA)担任综合研究员。她的研究聚焦于当代艺术和流行文化中的日本“萌”美学;近期,她关注人类世等研究方向,并参与了2020年度的研讨会“里斯本人类世校园:视差”(Anthropocene Campus Lisboa: Parallax | ACL: Parallax)。索萨博士的文章被Routledge和明尼苏达大学等出版社的书籍收录,她也经常会在会议和课堂中展示自己的研究成果。她共同创办了葡萄牙艺术团体“Clube do Inferno”和“MASSACRE”,并以笔名Hetamoé在国际范围内发表了她的漫画。个人网站:www.heta.moe.

Ten years ago, a hypnagogic anthem with feathery vocals and nostalgic electropop riffs went viral on Tumblr, the then-thriving microblogging website known as a popular hub for fandoms, the internet social justice movement, and subcultures. [1] The song was “Genesis,” the lead single from Visions (2012), the third studio album by Canadian musician and artist Grimes, née Claire Boucher in 1988, who now goes by the name c — the letter in lowercase and italics used to denote the speed of light in vacuum. [2] The song’s self-directed video was shot in Los Angeles, under the influence of trippy Boschian imagery and pastel grunge aesthetics. [3] Grimes and her girl gang rode in an Escalade through the desert, wielding swords and morning stars, looking impossibly cool. Brooke Candy walked the streets in a Final Fantasy-style silver body armor with high platform shoes raising her to the sky, white contact lenses, and black lipstick. Her shocking-pink hair fell in knee-length extensions around her body, like a braided curtain, as she sucked on a lollipop with bravado. In another sequence, Grimes was on the back of a limousine, partying with friends in an oversized sailor fuku jacket and Totoro backpack, holding an albino python on her shoulders in homage to Britney Spears’s 2001 VMA performance (Figure 1). [4] Her hair was tied in long, dreamy, blonde twin tails. Later, she posed in the woods with a group of ennuied hipsters. She played with fireworks, held a flaming sword like a divine messenger.

Figure 1. Still from Grimes, Brooke Candy, and their entourage in Genesis.

Despite its title, “Genesis” was by no means at the origin of evocations of an enticing “whiff of Japanese cool” in pop music videos from the West. [5] That honor, quite possibly, goes to one-hit-wonder The Vapors’s “Turning Japanese,” “widely regarded as one of the dumbest songs in pop history,”[6] complete with the infamous Asian riff and other orientalist stereotypes. [7] Since the 1980s, music videos referencing Japanese pop culture have mostly taken two forms. On the one hand, there are a variety of music videos in the flâneur tradition featuring Westerners wandering around Tokyo, perhaps sparked by the success of Sofia Coppola’s 2004 film Lost In Translation. In such cases, coolness becomes a natural part of the Tokyoite urban jungle and is both traditional and pop-cultural, like The Killers’s “Read My Mind” or The Black Eyed Peas’s “Just Can’t Get Enough.” On the other hand, some music videos directly reference pop culture “made in Japan,” often starring the artists themselves, their animated alter egos, or otherwise relating to the song’s topic, like Beastie Boys’ “Intergalactic” or t.A.T.u.’s “Gomenasai.” The most notable cases are those in which studio-style anime are produced for the music videos. For example, “Interstella 5555” (2003), for which the French duo Daft Punk enlisted the likes of Toei Animation and Matsumoto Leiji, Britney Spears’s “Break the Ice” (2008), and “It Girl” (2004), Pharrel Williams’s collaboration with Japanese artists Takashi Murakami, Mr., and Fantasista Utamaro.

“Genesis” is not an anime. Nevertheless, Grimes’s Japanese inspirations, from Yayoi Kusama to Kyary Pamyu Pamyu, from Akira to The Legend of Zelda, explain why she once tweeted that Japan was her “spiritual homeland.” [8] “Genesis’” release in the early days of 2012 makes it a trope codifier for a loosely defined movement in the contemporary arts that I refer to as a “weebwave.” Initially, the term “otaku” described all the obsessive fans of anime, manga, videogames, and other varieties of Japanese pop culture, regardless of whether the fans were Japanese or not. However, according to Know Your Meme, around 2002, a competing internet slur emerged that established a distinction based on the fan’s nationality: Wapanese, from “wannabe Japanese.” [9] Around 2004, “wapanese” turned viral in the English-speaking anonymous imageboard 4chan. It also became the source of many skirmishes among website users, to the point that moderators introduced a filter that replaced it with a new word — weeaboo. [10] In itself, “weeaboo” is a meaningless word first used in the webcomic The Perry Bible Fellowship by Nicholas Gurewitch, in which a character who dares to speak it gets tied up and spanked by a mob as punishment. [11] The word began to be used as a synonym for the contemptible wapanese and, over the years, it was shortened to “weeb.”

It did not take long for “weeaboo” to be reclaimed from insult to self-deprecating humor or even a badge of honor. Today, based on a bit of autoethnography, I would say that the weeaboos/weebs have eclipsed the otaku on the “Western” side of social media. The weeaboo’s mere existence attests to a previously nonexistent need to separate between ethno-racially or otherwise “authentic” fans and what is often viewed (even by those in question!) as a gratuitous appropriation of Japanese pop-cultural products. My reference to “Genesis” as a trope codifier of the weebwave intentionally refers to this, for lack of a better descriptor, “superficiality” or “shallowness.” In its clipped abbreviation, the “weeb” in the weebwave captures the twenty-first-century morphing of the otaku into the global weeaboo, and from there, into a coolified version in which weeabooness is more of a style of performance, a schtick. Within it, not real Japan, but mediated “Japan” (in quotes), becomes a nebulous, elastic, unfixed image which is a “natural” or “obvious” part of the consciousness of digital natives (i.e., millennials, Gen Z, and, soon, alphas), alongside a myriad of references to pop and internet culture. Moreover, while the weebwave is not limited to songs and music videos — certain forms of global manga come to mind, and one can encounter it in film and contemporary art — these are especially relevant for young audiences who spend a significant share of their time on websites like YouTube or Instagram, bypassing traditional forms of cultural influence. [12] Thus, the case studies in this article are songs and music videos whose “spreadability” [13] is apparent in that they are viral successes, namely, works by artists born between the early 1980s and mid-1990s such as Grimes, Vectroid and the vaporwave movement, Jon Rafman (with Oneohtrix Point Never), Princess Nokia, Josip On Deck, and Doja Cat.

The “naturalness” with which these artists, and weeaboos in general, are willing to be “Japanized” is, in and of itself, a bit of a defiance, especially when one considers that the worldwide success of anime and manga is frequently referred to by journalists such as Roland Kelts as a Japanese “invasion” or “revenge” against Western cultural hegemony. [14] Perhaps precisely because of these associations to cultural “impurity,” the perceived “transnational transgressions” [15] of “Japanization” lend themselves well to confronting “ideologies that phobically associate mass culture — and its ‘tainting’ or corruption of high modernist values — with female and queer bodies,” [16] as well as racialized, nonwhite bodies. It is worth mentioning that most of the artists in this article relate to “queerness” in one way or another, both in the sense of sexual and gender queerness and in a more general sense of nonconformity to social roles. For example, Princess Nokia is militant about their bisexuality, gender nonconformity, and mixed-raceness. Vektroid is a trans woman. Grimes cultivates an image of posthuman androgyny. Doja Cat and Josip on Deck are Black artists who challenge simplistic notions of racial and sex-gender roles through shock humor. Plus, this overview is far from exhaustive. There are many transgender and crossdressing Western artists who heavily reference Japanese pop and cute culture in their works (e.g., SOPHIE or Ladybeard).

Another fundamental aspect of the weebwave is its emphasis on DIY (“do it yourself “) aesthetics, the language of fandoms, and bedroom production. Indeed, while millennials may well be at the center of the “produsage revolution,” [17] consuming information online and creating and/or sharing digitally through a set of increasingly accessible resources and tools, it has been noted that “for younger generations, the internet is associated mainly with corporate, registration-only services,” negating the naive assumption that such new media contents are somehow more unrestricted than what we find in “old,” traditional media. [18] So, even though one could also qualify polished, professional-looking works like “Interstellar 5555” or Pharrell’s “It Girl” as weebwave, this article focuses on works in which the processes of “Japanization,” cutefication, and amateurization seem to coalesce into a stance that echoes a broader disenchantment toward Western modernity and individualism, brought about by the disastrous impact of late capitalism (or neoliberalism) on the global social-ecological fabric. Arguably, the disenchantment is just as present, even if with an inverse agenda, on the unpleasant fringes of this phenomenon, i.e., the disturbing intersections of anime fan culture with incel and alt-right movements, which, as we will see, is tackled by the example of Rafman in this article. However, before going any further, it is necessary to delve a little deeper into the distinction between the otaku and the weeaboo, where some of these tensions are already rooted.

Otaku and/versus Weeaboo

In the above introduction, I described the origin of the term “weeaboo”as arising from the necessity of distinguishing between Japanese fans of manga, anime, and videogames (the otaku) and the global fans of this same kind of products. Still, there are some nuances in the opposition between these two terms that this simple distinction does not quite capture. In contrast to the otaku, who keep their subcultural interests within the “appropriate” venues (i.e., contained or otherwise separated from non-fandom spaces, such as the neighborhood of Akihabara and Tokyo Big Sight), the prototypical weeaboo is ostentatiously, irritatingly, and gratuitously obsessed with Japanese pop culture, blurting out, nonstop, soundbites like sugoi, kawaii, desu, baka, and so on. By this definition, a foreigner can be an otaku if they behave — it is the excessive exteriorization of one’s fannish drives that disqualifies one from “proper”cultural membership. This widespread repulsion toward weeaboos is evident in the fact that there is even a WikiHow article on “How to Avoid Becoming a Weeaboo.” [19]

Considering that, in the popular imagination, the otaku are repressed into living a double life by Japanese society, [20] the rift between otaku and weeaboo acquires contours of what scholar Casey Brienza calls the “performance of ethno-racial authenticity” in “Japanized” fandoms. [21] More often than not, the rift is also gendered, as the weeaboo is stereotypically female or feminized by their appearance and taste. Indeed, searching for “weeaboo” on Google returns pictures of masculine Western men crossplaying as female anime characters like Kaname Madoka and Sailor Moon. According to the top entry in the Urban Dictionary, too, among other things, “a weeb is a non-Japanese male who watches and is a fan of CGDCT anime, has a waifu, a waifu pillow and is obsessed with Japan,” adding that “weebs are harmless” and that “they know they’re disliked by many people but they don’t give a fuck because they know they’re sugoi (awesome).” [22] This definition points to a prejudice against the “moefication” of the otaku industry in the 2000s, which perceives the boom of “cute girls doing cute things” (CGDCT) anime and manga and its feminizing influence as a threat to “serious,” gender-conforming male otaku who are into sports anime and science fiction. [23]

Ironically, as is well known in the field of “otakulogy,” in Japan, since the 1980s, the otaku have been suffering through their own sex-gender troubles, having been pathologized in the mass media as failed, effeminate men with a two-dimensional complex who are not into “proper” (flesh and blood) women. [24] Now, in the twenty-first century, this feminizing contamination — encapsulated in the association with crossdressing and the “nagging but harmless” stereotype — seems to transpose itself onto the weeaboo. At the same time, those in the West who have coined and shaped the meanings of the term “weeaboo” rehabilitate the original Japanese otaku with a newfound social and sexual virility which, in reality, they never possessed in Japan. In this regard, the various drawings or collages circulating online comparing the otaku and the weeaboo in a meme-like fashion are very revealing. Take the two examples shown in Figure 2. In the example at the top, titled “How to tell the difference between an otaku and a weeaboo,” one sees a side-by-side comparison between a low-profile male otaku, rationally discussing an anime, and a hysterical, inarticulate female fan ranting about “bishies” (short for bishōnen or “beautiful boy”) and “yaoi.” In the example below, the weeaboo is cutefied by doodles of anime eyes, blush stickers, and sparkles superimposed on their face while representing the otaku as a handsome, confident, square-jawed businessman. In both cases, the color scheme of blue on the otaku’s side and pink on the weeaboo’s side serves to reinforce the otaku versus weeaboo opposition as an opposition between male and female.

Figure 2. Examples of the “otaku versus weeaboo” meme.

I say this is revealing because it touches on another critical aspect of the rise of weeaboo as a slur, which is the fact that, in no small part, it is linked to a reaction against the growing vocalness, in the 2000s and 2010s, of the global fujoshi fandom, i.e., women and girls who are fans of boys love media. [25] Historically, female fans have been rendered invisible, or deliberately rendered themselves invisible to avoid being a target of ridicule, in the heteromasculine-coded spaces of fandom associated, for instance, with comics, which view male homoeroticism as an unwelcome intrusion. [26] With the rise of fujoshi-friendly online spaces like LiveJournal, Tumblr, and dedicated fanfic venues like FanFiction.Net and the Archive of Our Own, such fannish impulses gained unprecedented visibility in the West. Examples such as the ones in Figure 2 indicate a backlash against this visibility and vocalness, in which the otaku’s status is lifted at the expense of female fans — even though, in Japan, the otaku was, and still is, a stigmatized identity, and a feminized identity at that.

DIY Fan Culture, Cuteness, and “Japaneseness”

As demonstrated by the “Genesis” music video, bedroom production, not the professional music or animation studio, is at the heart of the weebwave. The frequent reliance on self-directed amateur footage, “poor” editing techniques (picture-in-picture overlays are a favorite), and fannish DIY tools aligns the weebwave with the community and collaboration-oriented practices of maker, hacker, and open movements (e.g., the open-source-software movement), signalizing that — in theory, if not always in practice — they go against a commoditized “shrink-wrapped” art and culture. [27] Thus, for these artists, music videos play a triple role. On the one hand, they not only constitute an essential artistic expression in and of itself, rather than being a byproduct of songs, but herald their belonging to a certain subcultural, mostly generational (millennial or later), identity, by way of the references to anime, manga, Japanese videogames, etc., that they deploy. [28] On the other hand, they show their rejection of teleological “techno-positivist innovation narratives” geared toward image perfection and cleanness, which justifies their preference for the techniques of amateur fan production. [29] In Grimes’s case, this post-digital ethos seems to meld with the posthumanist vibe of Japanese animation and video games that permeated Genesis and continued in many of her following videos from the 2015 album Art Angels (e.g.,“Kill V. Maim” or “Venus Fly”). [30]

Like her previous albums, Grimes herself made the art for Art Angels, only this time, the influence of Japanese pop culture intensified. The cover featured a digital drawing of a blue alien head floating in space, with pointy ears, a queue hairstyle, and three big, bloodshot anime eyes. On the right, there was a side panel with a pink-haired anime elf. Inside, various illustrations accompanied the record, filled with references to kawaii culture, high fantasy, internet memes, and graffiti. Like a sorcerer, Grimes stirred her magic potions in the massive cauldron of cultural memory, where high art meets “digital folklore” in a performance of globalness, and the past and the future become intertwined, flattened, and indistinguishable. [31] It did not stop there. It is true that much digital ink has been spilled over the unlikely love affair between Grimes and Elon Musk, the CEO of Tesla and one of the richest men on Earth, since their first public appearance at the Met Gala in 2018 (the couple’s first child, controversially named X Æ A-12, was born in 2020). Their relationship triggered outrage among Grimes’s fans, who saw this as a betrayal of her progressive, leftist ideology by literally sleeping with the enemy. [32] Nevertheless, Grimes continued to exert her trendsetting influence on the mediatic milieu, appealing to the cravings of a millennial crowd hungry for science-fantasy tales told in the trashy digital aesthetics of Y2K and internet-bred subcultures.

Grimes’s subsequent releases exacerbated the ubiquity of Japanese pop culture in her eclectic concoctions. Released in 2020, the album Miss Anthropocene (a pun between “misanthrope” and “Anthropocene”[33]) presented, on the cover, again, drawn by Grimes, a personification of anthropogenic climate change as a winged anime-style female character, rendered in 2D and 3D. The music video for the first single, “We Appreciate Power,” only included in the Japanese CD release, set the tone: sequences of Grimes dressed like an emo “e-girl,” holding a cute Sanrio-esque plushie against a cyberpunk background, then together with HANA (Grimes’s collaborator and touring back-up singer) posing as “beautiful fighting girls” in plug suits, armed with a crossbow and a sword like that in Revolutionary Girl Utena. [34] Another music video, “My Name is Dark,” included actual footage from Evangelion and the popular CGDCT anime Miss Kobayashi’s Dragon Maid, as well as a Snapchat filter of internet favorite Sailor Moon. Sailor Moon also echoes in “Delete Forever,” where Grimes, looking like “a final boss character in a game” (according to one comment), sings a poignant ballad against what could be a vision of Moon Castle in ruins. [35] Moreover, on YouTube, Grimes titled the video for “My Name is Dark” as “(NOT thee OFFICIAL VIDEOOO, just a cute vibe) Xxo,” a caption whose netspeak qualities — Xxo means “kiss and hugs” — reinforces and maintains her aura as a “bedroom producer,” casually addressing her fans on social media. [36] This, though she is by now a global superstar, and many of her videos have become highly produced operations.

Japanese animation references peaked in the video for “Idoru,” of which two versions, slightly shorter and slightly longer, were released. The song title is a pun between the phrase “I adore you” and a reference to William Gibson’s second novel in the cyberpunk Bridge trilogy, dedicated to the author’s daughter, Claire (i.e., Grimes’s birth name). [37] The video mixes two types of film. On the one hand, it features footage of a visibly pregnant Grimes, dancing in a flowy white dress against a flat pastel background, holding a sword amid a storm of digital cherry blossom petals. Her hair was made into pigtails, and she wore mismatched contact lenses. On the other, it includes video excerpts from cult phenomena like the Japanese videogame Nier: Automata and the iconic queer anime couple of Utena Tenjou and Anthy Himemiya (again, from Revolutionary Girl Utena’s series and movie). Much like “My Name is Dark,” “Idoru” prompted a flood of humorous remarks about weeaboos in the YouTube comments section: “So you’re telling me that Grimes and Elon Musk are huge weebs? I approve,” [38] “This is what happens when you give the class weaboo couple a budget,” [39] and “Grimes doing god’s work making weaboos cool again.” [40] Both these music videos expertly (re)produce the spontaneous DIY aesthetics of fan activities like cosplay, fan art, GIFs, and AMVs (“anime music videos”), using digital video filters, anime and videogame footage, and resorting to crude picture-in-picture overlays to deliberately create an “Internet Ugly Aesthetic.” [41] Her fans acknowledge this; as one YouTube comment states, “I love how her partner is one of the richest people on the planet yet she still insists on doing these ‘low budget’ DIY videos. We love a humble queen.” [42]

This humbleness is both genuine and a part of Grimes’s presentation strategy as “one of us” by referencing the anime shows or videogames that her generational peers love, frequenting their social media platforms of choice at a given time (e.g., creating accounts on Tumblr, then Instagram, and, more recently, TikTok) and using the tools of “produsage” employed by the fandoms themselves. For instance, two lyric videos (itself, a rather fannish expression) released in 2020, “Darkseid w/ 潘PAN” and “My Name Is Dark (Russian Lyric Video),” appear to use 3D anime models from Blender or MikuMikuDance, a freeware program that grew out of the fandom of Japanese cybercelebrity Hatsune Miku. In addition, because of the coronavirus lockdowns, Grimes decided to share with her fans via Wetransfer the raw media of her video for “You’ll Miss Me When I’m Not Around,” which she performed on a green screen. As she put it, “because we’re all in lockdown we thought if people are bored and wanna learn new things, we could release the raw components of one of these for anyone who wants to try making stuff using our footage.” [43] One also finds this collaborative and DIY ethos on her Instagram page, where Grimes has a story pinned to her profile dedicated to Grimes-related fan art. All in all, the fact that Grimes is “making weeaboos cool” exemplifies a crucial trait of the weebwave: the coolification of, and, to some extent, the standing up for, a generationally-specific subculture that is, by definition, the embarrassing and uncool byproduct — or, even, neurosis — of capitalist globalization.

Grimes also exemplifies a guerrilla strategy common to other artists in the contemporary art world and culture by reclaiming the “minor and generally unprestigious feelings” [44] and aesthetics associated with femininity, like the cute and the pretty, often combined with expressions of “the weird and the eerie.” [45] In 2013, Alicia Eler and Kate Durbin wrote about such strategic uses by girls and young women to craft their spaces online in an article titled “The Teen-Girl Tumblr Aesthetic,” which is the niche Grimes emerged from and whose modus operandi she still replicates. [46] While they do not explicitly say so, Eler and Durbin framed the teen-girl Tumblr aesthetic within a hauntological scope by referring extensively to the tragic death of Live Journal and Tumblr user Elisa Lam (and, for that, causing a wave of indignation in the article’s comments section). Curiously, the fact that Derrida’s concept of hauntology, coined in The Specters of Marx (1993), has itself been called “a cute and amusing play on ontology,” draws one’s attention to the largely overlooked role of the cute and the pretty within hauntological aesthetics, rooted in the music scene of the early 2000s. [47] Hauntological music pioneered, and to some extent engendered, many of the internet microgenres that shaped the sonic landscape of the 2010s, including witch house, vaporwave, and certain types of alternative hip-hop. The “genealogical throwbacks” [48] that characterize it are nothing new, but as Simon Reynolds argues, the amount of time separating the present from what is quoted seemed to shrink. “Earlier eras had their own obsessions with antiquity, of course, from the Renaissance’s veneration of Roman and Greek classicism to the Gothic movement’s invocations of the medieval,” Reynolds explains. “But there has never been a society in human history so obsessed with the cultural artifacts of its own immediate past. That is what distinguishes retro from antiquarianism of history: the fascination for fashions, fads, sounds, and stars that occurred within living memory.” [49] Such temporal proximity has paved the way for Japanese pop culture to be hauntologized by those in the West who have it in their living memory — namely, the millennials who entered adulthood in the first decade of the twenty-first century, amidst the democratization and advancements of the internet that magnified its global spread.

The hauntologization of Japanese pop culture is apparent in the microgenre of vaporwave, with its deliberately heavy-handed “postmodernness” exploiting the associations of East Asian imagery with “futurepast” consumer culture, cybercapitalist displacement, and techno-orientalism. [50] This techno-orientalism, developed “in the wake of neoliberal trade policies that enabled greater flow of information and capital between East and West,” [51] was shaped by Western imaginings of Asianized futures as well as Japan’s “complicit [self-] exoticism” [52] in the construction and commodification of Japaneseness, as the country became a sort of postmodern symbol, both in the eyes of the West and domestically. Indeed, according to anthropologist Marilyn Ivy, “postmodernism” was a widely circulated informational commodity in 1980s Japan, propelled by the boom of “new academicians” or “postacademicians” like author Akira Asada in the Japanese mass media. The popularity of postmodernism in Japan implicitly celebrated “the nation’s triumph over [Western] modernity and over [Western] history” from which the country had been denied “a full-fledged subject position and historical agency.” [53] Thus, the fact that vaporwave artists deploy anime characters and Japanese letters alongside other icons of corporate anonymity and escapist nostalgia (e.g., malls or ’90s television) [54] suggests that it is the concept of Japaneseness, in all its mukokuseki (“stateless”) or “culturally odorless” [55] splendor, that fascinates them — in other words, postmodern Japaneseness, or the Japaneseness of postmodernity, rather than any historically accurate version of Japan as a country. The quintessential vaporwave album, Floral Shoppe (2011), by American electronic musician Vektroid (Ramona Xavier), under the alias Macintosh Plus, is technically named フローラルの専門店 (Furōraru no senmon-ten) and its songs are all titled in Japanese (Figure 3, left). There is also an entire faction of hypnagogic pop in online audio distribution platforms, like Soundcloud and Bandcamp, whose songs and visuals are directly inspired by anime and manga. The Hong Kong-based record label Neoncity Records exemplifies this trend, hosting international musicians such as Mexican マクロスMACROSS 82-99, whose 2013 album SAILORWAVE (an homage to Sailor Moon) has been called an excellent demonstration that “weeb shit and vaporwave aesthetics is a deadly combination when done right (Figure 3, right).” [56]

Figure 3. Left: Cover of the album Floral Shoppe, by Vektroid. The artist’s and the album’s names are written in Japanese. Right: Cover of the album SAILORWAVE, byマクロスMACROSS 82-99.

My final example for this section is “Still Life (Betamale),” a video artwork by Canadian artist Jon Rafman (b. 1981). “Still Life (Betamale)” was initially posted to YouTube in 2013 as a music video for the homonymous song by Daniel Lopatin (b. 1982), better known under his stage name Oneohtrix Point Never. In what some considered “an unprecedented move,” the video was banned from YouTube, then re-uploaded to the video-sharing website Vimeo, only to be taken down again due to its explicit content. [57] Rafman has since re-uploaded it successfully to Vimeo, and the video is also available on both artists’ websites. Contentwise, “Still Life (Betamale)” is like a stream-of-consciousness record from the wrong side of the internet, rendered in sequences conveying an ethereal sense of eeriness. It includes everything from footage of amateur performers in furry costumes and animegao kigurumi (full-body character suits with anime masks) and other “creepy” kinks to screenshots and GIFs from 1980s and 1990s Japanese eroge (adult videogames). At one point, “Still Life (Betamale)” delivers a particularly feverish collage of pornographic images from Gurochan, an online community specializing in gory anime-style illustrations, often of the lolicon (pedophilic) variety. As Rafman explains, this close encounter with Gurochan reflects his process of surfing the internet ad nauseam: “There’s this moment at the climax of the film where there’s an enormous accumulation of this violent fetish imagery. I was trying to express the feeling of sensory overload after surfing the deep Internet and consuming so many images.” [58]

Fittingly, one of the first images to appear in “Still Life (Betamale)” is the photograph of a naked, obese white man coming “toward” the viewer, increasing in size from a tiny rectangle at the center of the screen until it occupies the whole field of vision. The man sits in a room covered in Japanese anime posters (a background eerily reminiscent of the famous 1989 photograph of the cramped bedroom of serial killer and “otaku murderer” Tsutomu Miyazaki), pointing two revolvers at his head while wearing a face mask made of pink panties printed with cute anime girls and two kid bikini tops (Figure 4). The image appears again in brief, quasi-subliminal flashes, with superimposed digital sweat beads running down its surface, in a glaring collage of photograph and computer-generated imagery. This squeamish body, about to burst from its limits, emphasizes the beta male that Rafman’s still life represents: not the nerdy Silicone Valley entrepreneur but the emasculated incel (“involuntary celibate”) whose resentment, misogyny, and self-pity constitute a toxic residue of hegemonic masculinity, threatening to spill from the fringes of the internet where it dwells and brews. Unlike the coolification of weeabooness in Grimes’s and vaporwave’s music videos, “Still Life (Betamale)” uncovers the underbelly of user and fan empowerment, namely, the “Beta Uprising.” [59] A revenge of the “pale, white and angry” [60] manosphere of internet forums like 4chan’s /r9k/ or Reddit’s r/ForeverAlone, enacted in fantasy, when not in reality — several mass murders and acts of targeted violence in North America were committed by self-identifying incels or men known to be aligned with the incel ideology, resulting in nearly fifty deaths. [61] In this light, the CGDCT-loving weeaboo no longer seems so “harmless.”

Figure 4. Still from the beta male in “Still Life (Betamale).”

There is an extra, less intentional, layer of interest in “Still Life (Betamale).” Rafman anonymously initiated a board in 4chan’s /mu/ category about the video, as a homecoming to the Mecca of viral content and shock imagery to which the video pays tribute. The thread is archived on the artist’s website as a forty-three‑page‑long PDF document, in which users react to and discuss the video at length. However, Rafman’s “online anthropology” itself became the target of disgust and contempt. [62] The document, heavy on internet slang, image macros, and reaction pics, records the extent to which Rafman’s artistic integrity is found problematic by those who are familiar with his sources, eliciting sarcastic comments like “this is just a bunch of tumblr and furry shit thrown together” or “wow, you have a tumblr! good job. furries are so WEIRD! japanese porn is so CREEPY!” [sic]. However, the most indignant comments revolved around Rafman’s use of over thirty screengrabs and GIFs of Japanese videogames from the Tumblr blog fmtownsmarty, without permission or proper credit. One fellow Tumblr user was particularly vocal in their protests, accusing Rafman of perpetuating the practice of slumming in and mining outsider cultures for cultural and social capital in the conventional art world. [63] On Rafman’s website, “Still Life (Betamale)” is now accompanied by a notice expressing “special thanks” to his many amateur sources (fmtownsmarty, Gurochan, various furry and animegao kigurumi performers, among others), whose tardiness and non-descriptiveness seems to have done little to appease his critics.

In contrast, in art magazines and the artist’s own words, Rafman is said to stand in “resolute solidarity with the virtual revellers who populate his work, from the denizens of Second Life to the ‘furry’ fetishists of 4chan.” [64] Like Grimes, he performs as “one of us” by appealing to “Japanized” subcultural references and replicating specific modes of produsage close to the hearts of millennials and younger generations. But the adverse reactions in 4chan and Tumblr against the appropriation of amateur labor by a professional artist hint at a more complex, certainly less harmonious, interplay between the realms of gallery art and the internet’s gritty back alleys. The fact that, despite adhering to a “cut and paste” culture that celebrates anonymity and permissiveness toward intellectual property — and that, according to “Luddite” writers like Andrew Keen, is “enabling a younger generation of intellectual kleptomaniacs”[65] — “Still Life (Betamale)” still ended up in a gallery in Chelsea [66] stresses the privileges and inequalities at work in the processes of art historical recognition, even within microgenres like the weebwave, and the resentment it generates in those excluded from it.

Intersections of Weeaboo, Gender, and Race

This section investigates some examples where the intersections of the weeaboo with race and culture are core to the songs and music videos. Take the case of Nuyorican (New York Puerto Rican) rapper Princess Nokia, the alter ego of Destiny Frasqueri (b. 1992). Princess Nokia often explores postcolonial and feminist themes in their songs, reflecting on their experience growing up in the Bronx, Spanish Harlem, and Lower East Side of New York. [67] A simple Google search returns various promotional photographs where they appear as comfortable looking like a Harlem tomboy as they do rocking a tight dress in front of a window filled with Hello Kitty merchandise. In one picture, Princess Nokia holds a stuffed Totoro toy, while in another, they stare longingly at the camera wearing a cat ear headband. Grinning, they smoke a cigar in a Pokémon shirt. The music video “Dragons,” a song inspired by Game of Thrones’s character Daenerys Targaryen, starts with an animated shot of Shenron, the magical dragon from the anime and manga series Dragon Ball (Figure 5, left). Through amateurish cinematography reminiscent of Super 8 film and “ugly” overlays and effects, “Dragons” shows Princess Nokia and their boyfriend in an amusement arcade, playing classic Japanese video games like Street Fighter (the camera lingers on Chun‑Li in a pink uniform) and Hatsune Miku: Project DIVA, mixed with sequences of anime and cartoons ranging from Dragon Ball and Pokémon to X-men and Winx. In the video, Princess Nokia’s bedroom is filled with posters and drawings of retro twentieth-century pop cultural icons — Star Wars, Bruce Lee, American comics, video games like Grand Theft Auto. At one point, the couple watches a VHS tape on an old television, curled up next to each other, in the intimate confines of nostalgia where today’s technology seemingly has no place.

Figure 5. Left: Still from Princess Nokia’s Dragons, featuring Dragon Ball’s character Shenron. Right: Cover of Metallic Butterfly, by Princess Nokia, featuring Hatsune Miku.

The cover of Princess Nokia’s debut album, Metallic Butterfly (2014), features a fanart illustration of Hatsune Miku (Figure 5, right). Set against an endless urban nightscape, the beloved, teal-haired Vocaloid icon perfectly incarnates the aesthetics of “high‑tech fairy music” [68] that, according to Princess Nokia, underlies the album (“The net is vast and infinite,” she seems to tell us, like Major Kusanagi in Ghost in the Shell). “Cybiko” and other singles from Metallic Butterfly are filled with references to cultural commodities made in the United States or Europe under the influence of Japanese pop culture: “Japanized” films and animations like The Matrix or Æon Flux, video games such as Mortal Combat, or bubbly cyber-orientalist Y2K aesthetics from the late 1990s and early 2000s. This focus on cultural ambiguity and masquerading becomes especially ironic considering recent accusations that Princess Nokia is “blackfishing” by exaggerating or impersonating Afro-descendant identities. [69] In any case, for artists like them, the “whiff of Japanese cool” comes from millennial nostalgia as much as from the associations that the globalization of kawaii and anime culture retains to rambunctious forms of hybridization or, indeed, cross-border “pollution.” As scholar Christine Yano points out, even seemingly innocuous characters like Hello Kitty can be perceived as bad role models, whose global spread engenders “a legion of vociferous detractors.” [70]

Meanwhile, American rappers like Josip On Deck (Josip Opara-nadi, b. 1993) and Hentai Dude (Colin Haynes, b. 1994) overtly reference Japanese pop culture in their songs and music videos. They hail from the microgenres of nerdcore hip-hop and comedy rap, immersed in the broader phenomenon of music scenes forming around SoundCloud and Bandcamp. Josip rose to internet fame on 4chan, with songs like “Anime Pu$$y” and “Mai Waifu,” rapping about anime and gaming while cuddling with his favorite dakimakura in home (music) videos. (Regrettably, as of June 2021, all of Josip’s songs and videos have been removed from his YouTube channel, except for “Anime Pu$$y” and a newer song, “Bape Store,” uploaded in March 2020) (Figure 6). Although 4chan is known to be a hub of virulent racism, Josip, who is Black, has been an avid frequenter since he was a young boy, [71] drawn like many others by the aspects of “chan culture” that originally sprang from otaku, gaming, internet memes (e.g., LOLcats), and hacktivist (e.g., Anonymous) cultures. Since Donald Trump’s election in 2016, 4chan has become linked to the “politically incorrect” internet trolls of alt-right and white supremacist movements. [72] Not that the toxicity was ever absent from such platforms; for instance, 4chan and Reddit had already been at the heart of harassment campaigns like Gamergate. [73]

In hindsight, this perceived shift “from anon to alt-right,” as writer Joanne McNeil puts it, complicates the candor with which Josip’s songs draw from 4chan’s political incorrectness to wallow in its most ridicule and problematic features. [74] Josip sings outrageous lyrics like:

Damn I love mai waifu, she ain’t nothing like you

She don’t bitch and nag me all the time up on her cycle [menstrual]

Damn I love mai waifu, her figure is so curvy

When you stand by mai waifu I can tell that you’re not worthy. [75]

Figure 6. Josip On Deck holding a dakimakura with the character Izumi Konata from the anime Lucky Star in the music video for the song “Senpai Gon Notice You” (2014).

The fandom slang “waifu” — the Japanese transliteration of the English word “wife” — indexes the male possessiveness toward moe characters that overlaps the misogyny in gangsta rap with otaku misogyny. In fact, the aforecited verses from “Mai Waifu” put the simultaneously “dehumanized and superhumanized, abstract and inanimate” anime waifu in direct opposition and clear advantage compared to real women, with their troublesome biological and organic functions. [76] In “Anime Pu$$y,” Josip unashamedly publicizes that “I wish all the girls in the world were animized.” [77] This slip from real “pussy” to the delusions of lonely otaku in love with fictional girlfriends mocks the absurdly “Japanized” weeaboo as much as the “tall tales of sex, drugs and destruction” typical of gangsta rap. [78]