2023-3-30 11:13 /

数据库中的动物

——飛浩隆科幻作品中的文本、空间、与集体存在

原作者:布莱恩·怀特(Brian M. White)

文章原名:Animals in the Database: Text, Space, and Communal Being in Tobi Hirotaka’s Science Fiction Literature

翻译:FISHERMAN

原文链接(Project MUSE)

译者按:飛浩隆《自生之梦》中篇小说资源链接,如果条件允许的话,烦请先读小说再看论文,以获得最佳阅读体验。

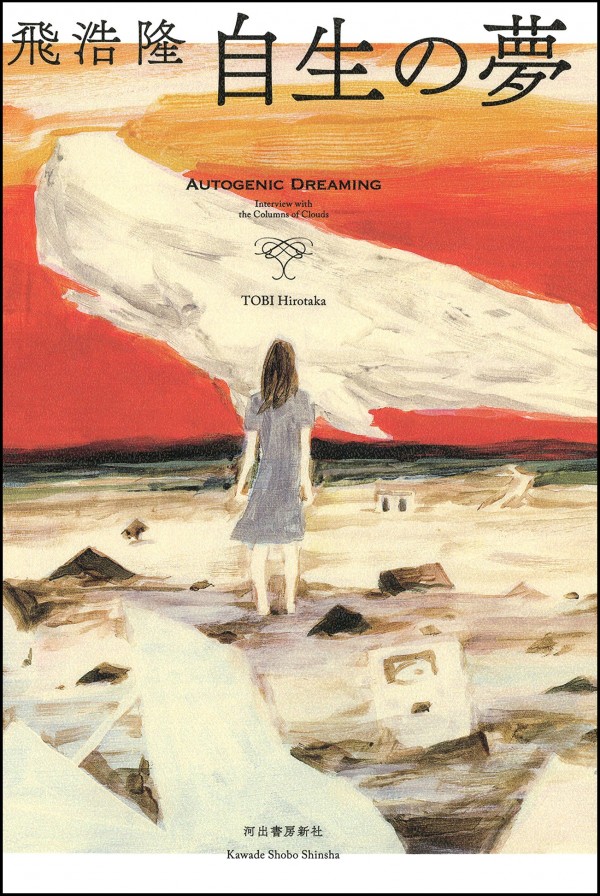

插画师agoera为2016年出版的飛浩隆短篇小说集《自生之梦》绘制了封面。画面中,一位女子正伫立在枯萎褪色的平原上(见图1)。在橘色的天空前,她背对观众,凝望着远方的地平线、和漂浮在其上方的巨大白鲸。和许多科幻插图一样,这幅作品用超现实的空间吸引了观众的兴趣。的确,各式各样的空间是科幻作品自早期以来便持续关注的事物。J·G·巴拉德就科幻新浪潮运动作出过著名的论述:「这场运动的标志,是从外部空间到内部空间的兴趣转向,以及,从外行星探索与征服的新殖民主义叙事到更多地从存在主义的角度关注身处后现代资本境况中的个体及其日常生活的转向。」[1] 随后的赛博朋克作品则将网络空间的数字环境主题化,并赋予蓬勃发展的计算机技术以内部扩展性——数字化的人类意识可以在其中移动。科幻的空间,是界定其主体的环境:无论是黄金年代科幻和赛博朋克作品中的外星/数字殖民边疆、新浪潮科幻中后现代妄想症患者眼里的强迫系统、还是后末日叙事中艰难困苦的自然状态。

图1.『自生の夢』的封面。飛浩隆著,河出書房新社出版,东京,2016年。艺术家:agoera,他的个人网站为:http://agoera.org/

如封绘所示,飛浩隆的短篇小说也将空间作为其组织结构的中心。作者所说的“自生之梦”四部曲包括一部中篇小说和三部短篇外传(首次发表于2009-2015年间)。第一篇小说,也就是和四部曲同名的《自生之梦》在发表后当即获得好评,并为飛浩隆赢得了2010年度的星云赏(日本最大的两个科幻奖项之一)最佳短篇小说奖。[2] 四段文本构成了“自生之梦”四部曲:它们分别提供了一段围绕着数字空间这一中心主题展开的不同插曲。数字空间是四部曲的、也是穿行并栖居于四部曲中的实体的背景——飛浩隆称其为「数字文本空间」(digital textspace,日文罗马音为:denshiteki moji kūkan)。飛浩隆的注意力几乎全部集中在了数字本体论的问题上。他提出了这个问题:在完全数字化的领域中,存在与生成(being and becoming)的本质是什么?飛浩隆在数字空间和数字生命问题上所采取的独特的“生态式”处理方法,为数字社会中主体性的新认知指明了方向。

构(梦)想文本空间

《自生之梦》是四部曲中最早发表的,不过,它在四部曲所描述的各种事件中排在第三位(叙事顺序上)。它的三部外传均进一步探讨了数字空间与数字生命的含义——通过围绕外传主角之一,即才华横溢的数字诗人爱丽丝·沃恩【译注1】的生与死展开的小插曲。这样一来,它们使得“自生之梦”式的数字文本空间以及其中的非人主体更加细致入微。叙事顺序上排最早的故事《#银之匙》(#銀の匙,2012)详细描述了新生儿爱丽丝的父亲理查德所发明的「卡西代理端」(Cassys,指AI算法文本程序,详见下文)以及使之成为可能的通用计算与网络基础设施。《在旷野》(曠野にて,2012)的故事发生在五年后的一个儿童训练营,在那里,年幼的爱丽丝与她的朋友克哉(Katsuya)同他们的卡西代理端玩游戏,并尝试了数字代理端能够实现的各种创造性生成。卡西,不仅仅是简单的信息检索与信息参考工具;孩子们展示了卡西代理端的潜能,特别是它们在集体艺术实践模式中与人类用户合作的能力。《野生的诗藻》(野生の詩藻,2015;标题化用自水見稜于1982年发表的短篇小说《野生の夢》)的时间线则跳转到了“自生之梦”事件和爱丽丝去世的几年之后:爱丽丝的朋友克哉和哥哥杰克正努力遏制着她遗留下来的破坏性“流浪诗”,后者是爱丽丝留在数字空间中的某个未完成项目的一部分,而现在这些诗歌对其他用户构成了威胁。这个故事勾勒了爱丽丝设想的数字文本空间的变革,以及它对数字主体的影响。总体来说,四部曲的叙事弧记录了文本空间与卡西AI代理端朝向愈来愈独立的存在形式演变的过程。

《自生之梦》中的数字空间,既是故事的背景,亦是故事中的角色之一。这部中篇小说讲述了一个名为「GEB」(Godel’s Entangled Bookshelf,即:谷德尔纠缠书架)的超大型数据库的故事。GEB类似于博尔赫斯作品中的总图书馆(Total Library):它不仅存储了人类文明有史以来所记录过的每一份文档,而且还存储了这些文档的翻译副本——它们被翻译成了人类所使用过的每一种语言(现存的/灭绝的)。然后,这些文档被标记、索引、交叉引用、并相互链接,以此创建一个远超其各部分之总和的整体。《自生之梦》中的GEB正受到名为「忌字祸」的病毒的攻击,而小说讲述的正是GEB同忌字祸战斗的故事。这个故事的叙述者是若干的卡西代理端,其英文全名为“Complex Adaptive Software Systems”,缩写为“Cassy”[3],意为:“复杂适应性软件系统”。基于AI的卡西是维护GEB并运行其搜索查询的“文本代理端”。它们创造了作家兼连环杀手间宫润堂和诗人爱丽丝·沃恩的数字再生体(reincarnation),而众卡西代理端则希望通过他们来遏制忌字祸对GEB构成的威胁。正如故事所解释的那样,所有的文本操作才是使故事以实在形式出现在读者面前的原因;叙事世界及其主角仅作为GEB内部编译的数据而存在。

自然语言

数字生命形式的本质是什么?怎样才能更好地理解它们?自生之梦四部曲所提出的这些本体论问题当即触及了「文本」这一议题。像赛博空间那样的数字“空间”,实际上只是通过解析计算机文本代码而创建的可视化(主体)和模型;有鉴于此,对数字生命的任何考量都必须将文本和语言视作由这种方式所建构的主体性的基本本体构成要素(ontological components)并将其纳入考量范围内。因此,飛浩隆向读者发问:迄今为止,数字生命通过语言表达的霸权编码而得以成形,然而,它将如何超越主体性的霸权模型、并生成出人意料的/与众不同的全新形式?如蕾切尔·杜马斯(Raechel Dumas)所言,「飛浩隆以理论上无边无垠的赛博空间辖域为载体,探索了语言从现有的表征系统中产生、并生成逃逸线(lines of escape)的方式。」[4] 在此,飛浩隆所选择的“数字文本空间”这一名称的重要性开始映入眼帘;不过,若想把握住赛博空间到数字文本空间的这种术语变革的全部涵义,则需更加深入的理解。

在“自生之梦”系列故事中,文本在被读者阅读时与数字文本空间建立起了关联,而故事的高度指涉性则在形式上部分反映了这一点。我们已经看到了对《白鲸记》的引用,但《自生之梦》不止于此;它还引用了许多其他的经典作品——从《沉默的羔羊》,再到《蜂巢幽灵》。另外,通过与读者的多次直接对话、以及对所采用文本形式的自觉式指涉,四部曲打破了它背景中的封闭虚构世界,并将其对非人空间和非人存在的关注拓展至读者生活的世界。飛浩隆的文本并不是对“科幻作品的非历史性未来中的人工生命”的想象。恰恰相反,他的文本促使着我们思考文本自身与当下的物质现实之间的关联。

那么,飛浩隆的数字生命形式理论意味着什么呢?让我们再次回到《自生之梦》短篇集的封面。该插画并未使用数字空间的常见视觉语言,后者由二十世纪八九十年代的赛博朋克作品发扬光大。我们没有看到覆盖在无边无垠的无特征领域上的笛卡尔坐标网格,也没有看到一行行浮动的文本和代码,更没有看到平滑的流线型抽象形状与实体【译注2】。恰恰相反,封面对文本空间(画面中的空间即为文本空间,短篇小说将向我们揭示)的描绘向我们展示了一个有着可被识别的人物和动物形象的自然空间,即便它是荒无人烟的、超现实的。agoera用于绘制这一场景的粗糙笔触使其看起来崎岖不平、未经打磨,与数字空间的传统形象相异;这里的数字空间更像是一块块漂砾,而非光滑的宇宙飞船。飛浩隆四部曲中的文本空间代表了从生态角度对数字空间与非人生命的再思考;它探索了文本在集体生成与个人主体性方面所能够发挥的,如同生命一般的积极作用。我们将会看到,《自生之梦》打破了自然界和(数字)文化的二元对立。小说强调:它们由彼此相互塑造而成,而且双方都塑造了我们与世界的主观接触;这篇小说促使读者走出传统印象中的数字空间,将注意力转向偶然(生成)的集体生命空间(spaces of contingent communal living),并接受在那里交织在一起的,人类、数字、和自然的语音。

因搜索,而存在

搜索查询与(输出显示)搜索结果的对话式过程是《自生之梦》世界中字面意义上的生成行为。小说开头附近的一段话清晰地阐明了这一点:「这个故事——姑且不论这能否算是故事——是与著名作家、杀人犯间宫润堂的长篇对话记录...并且,这场采访、进行这场对话的行为本身,也正是与‘忌字祸’的战斗。」[5] 换而言之,《自生之梦》中的语言和行为被认为是等价的。由卡西代理端编译的主要角色,是年轻的天才诗人爱丽丝·沃恩以及多产作家兼连环杀手间宫润堂的数字再生体。他们的存在本身、以及他们在文本中的行为均基于以下流程实现:首先,卡西代理端向GEB提问,然后,它在GEB的数据库中搜索爱丽丝和间宫润堂的作品以及其他相关文本,最后,卡西编译并输出答案。换而言之,这些主体并没有本质上的内在性。爱丽丝与间宫润堂的本体(存在)是完全关系性的:他们由文本数据中、以及各段文本数据之间数以千计的链接构建而成,并且只作为故事的观众所阅读的文本产品而存在。这些关系的检索与激活是使爱丽丝和间宫润堂被生成、并在文本中出现的原因。他们的主观现实化(actualization)完全归功于档案数据的检索和档案关系的揭发。

“爱丽丝”和“间宫润堂”的存在背后的请求-响应式(搜索-输出式,或许这样说更为妥当?)本体论模型在结构上和路易·阿尔都塞的理论——「意识形态对主体的询唤,是使得资本主义阶级社会中的劳动分工永久化的意识形态国家机器(ISA)的一部分」[6]——有着些许相似之处。在某一幕中,间宫润堂询问书写着他的卡西代理端:他的存在“源泉”位于何处?卡西回应道:它们正通过在GEB数据库中发起大量的搜索查询来编译“数以万计的间宫润堂”[7],而每一次搜索查询都和间宫润堂的人生以及他的书面作品之间有着某种关联。正如统治阶级的意识形态藉由询唤行为将个体转化为主体、并使之屈从于某政权的国家机器(state apparatus of power)那样,我们可以将卡西代理端的程序流程理解为:通过“搜索与间宫润堂的人生、他的作品相关联的档案”这一行为,字面意义上地书写间宫润堂,并使他成为“为GEB服务的间宫润堂”(将他书写为主体)。阿尔都塞的主体始终是处于与国家的权力等级关系当中的主体,同样地,这里的间宫润堂也只是因GEB而存在、并为GEB效力的“间宫润堂”。正如意识形态国家机器将个体询唤为主体,藉此再生产那些维持国家机器的生产条件那样,卡西代理端从数据库中编译了间宫润堂:这样一来,他便能击败忌字祸、并使GEB恢复原状。

《自生之梦》中的忌字祸之所以对GEB构成威胁,恰恰是因为它在语言中引入了不可量化的关系,从而使数据档案在形体上以可怕的方式扭曲变异、不再简洁明了。随着文字增殖、混融、合并、分割、并溢出文本界限,文本的数字表现形式怪异地膨胀了起来。换而言之,忌字祸通过改变文本之间的关系(这是数字文本空间中所出现的角色的本体论基础),从而促成了新的文本生成(即主观生成)。杜马斯就忌字祸给出了令人信服的解读。她认为忌字祸代表了与性差异(sexual difference)相关的、无法表达的创伤,并最终将病毒定义为:「它并不是朝向意义之死的某种姿态,而是一个场所,在那里,无法表征(elude representation)之物仍被登记成异质编码。」[8] 虽然作者对杜马斯的阐释没有异议,但作者还是想说:忌字祸在为个体主体提供精神分析视角的同时,亦是主体间的、即社会意义上的事务(transaction)协商场所。因此,文本和文本间的关系不仅是数字生命形式表达自身的手段,而且还是它们存在的根本。

数字存在之间的关系必然带有一定程度的不充分决定性(underdetermination)——《自生之梦》的文本即是从这一点上开始偏离阿尔都塞的「多元决定式(overdetermined)阶级主体」概念。述说故事的卡西代理端断言,尽管GEB进行了彻底的编目和量化,它在本质上依然是完全不可知的。小说语境中的全知,也就是对某人或某物的各个方面所进行的多元决定式量化,和受到质询的主体的死亡有关。这便是间宫润堂得以谋杀数十名受害者的原因,在小说中,他被描述为有着能够根据与某人相关的任何微小细节来创建这个人的完整精神轮廓(psychological profile)的超自然能力。在完成创建后,间宫润堂便可以通过与受害者对话,将这种认知植入其体内、并使其彻底认知自身。由于受害者自身的任一部分都被充分决定、并且失去了改变与变革(change and transformation)的可能性,所以,「他们的内部构造(心理结构)完全崩溃」[9],而后,受害者们自杀。因此,尽管像GEB这样的超大型数据库最初看似会对包含在其中的主体进行全景监视,并全面、多元地了解这些主体,文中对间宫润堂侧写能力的描述表明:任何形式的生命活动,不论它位于文本空间之内还是之外,都依赖于某种“必须在主体间交流时才能被发现的”暂不可知的元素。

飛浩隆的主体性模型将他笔下的角色转向外部,并使他们不断搜索(和实现)意料之外的全新关系和变革。在这一过程中,卡西代理端成为了活跃的协作者:它将爱丽丝·沃恩这样的主体扩展到其身体能力所及范围之外,并为他们提供了新的表达方式。我们将会在《野生的诗藻》的某段倒叙中看到阐明了这一过程的例子。在那段倒叙中,十岁大的爱丽丝正在向她的家人、朋友和粉丝展示她最新的“诗歌”。这首诗实际上位于一个复杂的AI程序之内,后者在AR中被视觉化、并以“诗兽”(poetical beast)的模样显形。飛浩隆将诗兽比作荷兰艺术家西奥·詹森(Theo Jansen)的“仿生兽”(Strandbeest)动态雕塑——一种由木头和帆布组成的聚合体,它可以捕捉并利用风力来移动雕塑的腿部,使其行走。[10] 在这段情节中,文本生产为爱丽丝的诗兽提供了行动的动力。她和运行诗兽程序的卡西代理端之间的嵌套结构(imbrication)被部分揭示:「在卡西代理端的支持下,爱丽丝以成年人的口吻说话。」叙述者说道。[11] 飛浩隆用这段描写暗示:爱丽丝作为成熟艺术家——这是她所建构的身份——表达自身的能力需要部分依赖她的卡西代理端实现。没有这些文本代理端的话,爱丽丝便无法成为读者熟知的爱丽丝。

对于尚未完全掌握其语言能力的幼体(此处指爱丽丝)来说,卡西代理端不仅仅是为之服务的表达补充装置/辅助义体——也就是说,它们并不是身为独立艺术家的“原本”或“本真”的爱丽丝的附庸;它们在表达行为中被视为爱丽丝的对等伙伴。在小说中,爱丽丝向她的观众解释:诗歌和读者交会的那一瞬间所蕴含的能量,为诗兽的持续生成提供了动力;对此,在场的一位评论家回应道:「我明白了...诗兽是一种‘运动’(movement)。」叙述者娓娓道来:「它并不是独立的诗歌,也不是诗集。一种突发的文本运动激活并驱动着这头野兽的形体和行为——这种‘运动’由某首吸引了众多‘诗人’的诗歌激发。」[12]《野生的诗藻》中的卡西AI对彼此的(数据)输出做出反应,以至最终,它们的行为变得像是一个活跃的艺术家集体那般:代理端互相消费着彼此的作品,并以创作诗歌作为回应。在爱丽丝设定初始参数后,卡西AI近乎完全独立地行动。爱丽丝在诗歌创作实践中与卡西代理端合作——后者不仅仅是这位艺术大师的工具,而且还是她在艺术上的合作者。

上文和《在旷野》中“爱丽丝和克哉同他们的卡西玩耍”的这一幕交相呼应。在前传《#银之匙》中,卡西代理端本质上是自动化的推特账号:它通过全球数据基础设施跟踪用户、记录他们的活动、将这些活动与从网络上收集的大量数据进行交叉引用、并以用户本人的语音将文本输出回网络中。正因如此,这些AI在《#银之匙》中首次登场时被称为“生活记录书记”(ライフログ書記)[13];此后,卡西被频繁地描述为“书记”,而这则暗示了它们与原本的、本体论意义上的人类之间的衍生关系。然而,《在旷野》中的爱丽丝和克哉玩弄起了卡西代理端动态自主行动的能力。该能力通过创建算法实现,而卡西则用这些算法在AR中组装幻想情景,以供孩童们娱乐。我们再一次看到:爱丽丝处理卡西的方式以艺术维度上的平等为标志,以至于她的AI代理端能够基于爱丽丝本人所给出的任何特定指令来动态演化它们搜索和吸收信息的方式,并最终超越她的指令行事。在小说中,克哉被比作一位使用着多种工具的艺术大师,而爱丽丝则更像是某个艺术家集体的一员:AI是她的创作伙伴。

阅读这野性的自然【译注3】

在《自生之梦》四部曲中,主体性的“离心运动”——即,主观身份从它的物质存在向外移动,以便和超越主体身份之物合作、并将其涵盖于自身之内——被反映在飛浩隆作品中所描述的“‘离心运动’与计算操作和数字空间的特殊关系”当中,并依赖于这种关系;反而言之,飛浩隆的作品在日本“数字饱和”(digitally saturated)的历史时刻中的所在(原文为place,译者注)则反映了作品自身。与之前的众多赛博朋克和科幻新浪潮小说相比,他的小说以略微不同,但在关键层面上与前者大相径庭的方式“思考着科技”[14],特别是计算机技术。如此一来,飛浩隆勾勒了高科技资本主义境况下的主体性:它不仅是个体性的,而且还是社会性的。

在考虑《自生之梦》中的卡西代理端时,我们必须牢记它们同GEB和“数字文本空间”之间的关联。小说中的空间与人们对数字环境墨守成规的想象形成了鲜明的对比:它打破了与赛博空间概念最密切相关的科幻运动——即赛博朋克流派——当中的,时髦的(后)现代技术恋物癖。我们可以在这种空间中发现它和为了应对赛博朋克主题而兴起的批判性后人类主义学术研究之间(颇有成效)的共鸣,而后者的学术语言则为探讨飛浩隆的作品提供了实用的起始点。然而,尽管飛浩隆用于描绘“文本空间的数字环境及其所包含的超大型文本数据库(即GEB)”的语言与批判性的后人类主义思想有所重叠,但它却超出了该理论框架的解释范围。

述说《自生之梦》的卡西告诉我们:GEB超出了任何人类的理解能力,没有人能够完全掌握它的详尽信息。然而,这些代理端的遣词造句却甚是耐人寻味:「(GEB是)一个谁都无法把握的意义、思维和联想的巨型复合体」,叙述者说道,「这已然等同于‘第二自然’的出现了。」[15] 这种选择从自然主义的角度来考虑GEB的做法在四部曲中不断地重复、并延伸到了对更广泛的数字文本空间的思考当中;这表明了飛浩隆对GEB和数字文本空间的持续关注。例如,在《野生的诗藻》一文中,爱丽丝在她的诗歌演示过程中向她的观众展示了支撑着她的诗兽进行演变的算法后台——她称之为「poésispace」(下文将其直译为“诗歌空间”)——的视觉化。诗歌空间被描绘为这样的一个地方:「来自世界各个角落的新旧文本平等地浮动着,而无数的数字代理端则在文本沉淀中穿梭;它们挖掘、切割着这些文本,将它们粘贴、缠结在一起,并孕育出更多的文本。诗歌空间就像由文字组成的松软土壤一般,庇护着众多的微生物与蚯蚓。」[16] 正如我们在这里所看到的那样,比起大多数传统科幻小说中的数字空间,飛浩隆作品中的是一个更为自然(earthier)的场所。

正如威廉·吉布森《神经漫游者》(Neuromancer,1984)中的赛博空间所体现的那样,科幻小说中的数字空间通常被理解为一种以「同感幻觉」(consensual hallucination)【译注4】形式存在于用户自身意识中的空间幻想,例如这一选段所述:「它是人类系统全部电脑数据抽象集合之后产生的图形表现...它是排列在无限思维空间中的光线,是密集丛生的数据。如同万家灯火,正在退却……」[17] 这里的数字空间极度内向化(introverted),纵使它有着高度网络化的性质。更重要的是,这种空间是作为数据的抽象而存在的,也就是说,它是与假定本真的客观现实相差了两个维度的“抽象的抽象”。吉布森笔下的主角凯斯对赛博空间的主观体验亦是如此:「那水一般的霓虹如同繁复的日本折纸,现出他那触手可及的家园,他的祖国,像一张透明的三维棋盘,一直伸到无穷远处。那只内在的眼睁开了,他看见三菱美国银行的绿色方块,后面东部沿海核裂变管理局耀眼的猩红色金字塔,还有军队系统的螺旋长臂,在他永不能企及的更高更远处。」[18] 同样地,对经过可视化渲染后的赛博空间的类比描绘不仅完全是几何和人工的(梯形金字塔、绿色方块、无穷无尽的网格空间),而且还是极度个人化的(他的家园、他的祖国),同时也是企业化的。如果说飛浩隆的数字文本空间是一个平行的自然世界,那么吉布森的赛博空间则是字面意义上按照资本主义的所有权与访问权逻辑被划分开来的空间。

诗歌空间在上述场景中的引入进一步细分了飛浩隆的数字世界模型,尽管前者在某种程度上更容易令人联想到生态位(evolutionary niche),而非吉布森笔下的封闭式社区。实际上,数字空间成为了一个伞式术语:它涵盖了数字文本空间和诗歌空间这两个不同种类、但又互相连结的领域。正如我们所看到的那样,前者是GEB、卡西代理端、诗兽、以及迄今为止讨论过的所有其他“由算法或文本构成的主体”的领域。文本空间,是文本和它们彼此之间的关系已被个体化、并被赋予了稳定的本体论基础的地方,而像爱丽丝、间宫润堂或诗兽这样可以被识别的主体则能够从文本空间中被识别出来。相反,诗歌空间则处于“永无休止的状态,在诗歌成为文字之前”[19];它是一个与人类的创作过程大致相似的、变化多端的前语言空间。《野生的诗藻》中的叙述者是这样描述诗歌空间的:

如同蚊群一般的文字(moji)构成了无数漂浮在广袤空间中的球体。这一团团文字就像呼吸一样膨胀、收缩;它们漂浮着,旋转着,上下前后左右移动着...偶尔,一团文字会吸引并吞噬另一团文字。有时它们也会排泄(出文字)。[20]

飛浩隆在描写“爱丽丝向她的观众展示原始文本开始‘独立成诗’的那一瞬间”这段情节时所使用的语言风格依旧是自然主义式的,始终如一。他先是援引微生物学领域的术语,然后,转向使用地质学中的专有名词——「顿时,文本球体的所有边界崩溃,就像细胞壁溶解在基液中那样...从文本的泥潭中,一种具有意义的形式伊始成形:这一进程类似于过饱和溶液受到刺激时的晶体析出过程。」[21] 在这里,一个全新的数字主体从诗歌空间的海量文本中诞生,但正如前文所述,数字文本空间中的主体被诗歌空间混沌的不充分决定性持续驱动着。文本空间的存在要归功于该空间当中的可识别主体(例如间宫润堂),后者采取了有意义的行动以遏制忌字祸对文本空间的毁坏。不过...虽然保留下来的文本空间是四部曲的主要背景及其关注对象,但是,诗歌空间所生成的文本间关系性(relationality)的变幻莫测的力量,就在文本空间的表面之下!它是使文本空间得以存在的关键组成部分,就像肉眼看不到的微生物驱动着我们眼中的自然世界继续运转下去那样。

有鉴于此,我们得以更为全面地理解由忌字祸引起的GEB文本数据库的扭曲变异。在《自生之梦》的末尾,以大白鲸莫比·迪克的形态现身的忌字祸被石化,而爱丽丝的数字再生体则站在这具岩石跟前,反思着忌字祸的本质。她凭直觉认为,忌字祸由所有GEB无法分类的文本间关系构成。「GEB无法处理挖掘出的结果。因为它们从未有过(被分配过)名字。GEB丢弃了不知几百万次...直到(它们)积累成‘忌字祸’这个动态构造,卷土重来...(忌字祸)没有名字,所以位于‘书写’之外。(它们)只能通过风的缀织书写。”」爱丽丝说道。[22] 忌字祸正是那些涌向完成了个体化的文本空间领域的,诗歌空间的前-个体化内容。它是纯粹的创造性、纯粹的关系性,只通过与其他文本的关系表现出来,也就是说,忌字祸只通过它对文本的影响显形,就好像风只有作用于其他物体上时才能被看见那样。

相比之下,间宫润堂通过创建某位个体的完整精神轮廓(这是他的天赋)从而对其进行多元决定的这种能力,则和忌字祸的恰恰相反。小说结尾部分的忌字祸看起来就像是被石化了一般,这是因为,间宫润堂已经使忌字祸彻彻底底地了解了自身:它被量化、被多元决定,以至失去了任何变革的可能性,正如间宫润堂在现实生活中对他的受害者所做的那样。解决忌字祸的这种方式在《野生的诗藻》中亦有展现:杰克·沃恩和爱丽丝的儿时玩伴克哉阻止了危险的流浪诗兽——但他们并没有摧毁诗兽,而是将它冻结,并使其进入生命暂停(suspended animation)的状态。静止,标志着这些矛盾冲突的解决以及文本空间自身的分解(resolution);这两段情节的背景环境类似于死气沉沉而又贫瘠的盐碱地,小说如是描述。某种程度上,数字文本空间本身仍是无生命的,纵使我们可以在其中发现众多主体之间的动态关系。

但是,忌字祸和诗兽为我们指出了文本空间看似不可避免的演变(方向)。即使间宫遏制住了忌字祸,但病毒的基本性质(即变革自身)表明:它最终会突破间宫润堂的抑制。《自生之梦》中的叙事者甚至告诉我们——「(忌字祸)也许马上就会狂暴起来,挣断绳索。」[23] 变革在文本空间中似乎势不可挡,而爱丽丝和间宫则好像都未将“阻止变革”这件事放在心上。两人推测:他们自身之所以被GEB编译,有可能是因为数据库希望榨取忌字祸内部蕴藏的“鲸油”。换而言之,GEB希望利用忌字祸所体现的创造性力量以推动数据库的进一步扩充与发展,正如捕鲸业助力西方的工业革命那般。然而,爱丽丝和间宫润堂似乎领会了GEB(真正)所需的东西:另一种变革,一种更符合忌字祸的性质、以及飛浩隆所构建的数字空间性质的变革。

在《野生的诗藻》中,爱丽丝本人就数字文本空间的变革给出了另一种生态学式的发展模型。我们得知,爱丽丝在她意外身亡前一直在开发着某个大规模的新型诗歌项目,后者旨在将气候/地球科学模拟程式纳入其数字文本空间作品当中;爱丽丝的终极目标是在文本空间中创建一个完备且独立的生态系统,在那里,她的“诗兽”和“诗鸟”可以生存、成长、并繁殖(大概)。爱丽丝曾希望为她的造物创建一个自生的环境:「这不是诗歌所描绘的天地」,叙述者澄清道,「恰恰相反,世界中发生的所有物理化学反应都将由“用文字写就的‘(唯一)一首诗歌’”生成,仅此而已。这是,所有产物亦即单单1首诗的世界。」[24] GEB试图分割并利用诗歌空间的创造性能量,而爱丽丝则希望将这些能量释放于文本空间自身之上,为的是让这些能量像塑造我们所处世界的自然现象那样给文本空间带来变革。然而,爱丽丝的项目因她的死而中断;“上述的变革是否会实现?”飛浩隆的四部曲暗中向读者发问——这仍是一个悬而未决的问题。

用风书写 – Writing With The Wind

从赛博朋克文学到《自生之梦》的转变反映了(虚构文本和现实社会中)自“终端”[25] 网络——即,只能通过独立、固定的计算机终端访问的互联网——向无处不在的移动分布式网络基础设施(它可以从各种设备上访问)的转变。换言之,网络技术和人类与数字网路的交互并未走向《神经漫游者》等作品中所呈现的那种令人上瘾的病态关系,而是愈加环境化(ambient),并成为了日常生活环境的一部分,特别是在当代日本流行文化中,这种拓展已经在“资本势力范围的扩大”和“消费行为同个人身份的交织”这两个方面被讨论过了。媒介产品对消费主体日常的「向内殖民」(endo-colonization)[26] 以及数字文本空间在信息技术普及的同时将文本性扩展到通用计算基础设施环境当中的现象,似乎不可避免地与后现代晚期资本缠结在一起:它似乎鼓励着空间的个体化、私有化和货币化;它侵蚀了公共领域,令其让位于唯我主义式的、极度个体化的当代生活消费经验。抵抗(向内殖民/后现代晚期资本/侵蚀)是可行的,但只能通过从媒介文本中获取主观价值的方式实现,纵使这些文本已被嵌入消费系统当中。

和虚构文本的这种独特的拟社会关系(parasocial relationship)经常被认为是御宅族消费者的一个显著特征;这种关系将御宅族塑造成了抵抗资本主义逻辑的矛盾主体,同时,它也在御宅族身上体现了“作为消费主义的主体性”的神化。斋藤环将御宅族定义为「特点是...能够从多层次的虚构性中取乐、并认识到日常现实本身就是一种虚构」的主体(英文原文引自J·基斯·文森特 [J. Keith Vincent] 翻译的《战斗美少女的精神分析》的导言部分)[27],而东浩纪则指出:构成御宅族媒介的重组(recombinant)美学元素的深层“数据库”结构,亦是御宅族的消费客体。[28] 围绕着御宅族形象的社会焦虑将“对主体和文本性之间联系的认知的增强”与人际关系的恶化混为一谈。也就是说:大量接触渗透到人类日常活动领域的文本,实际上只是将自己沉浸在资本主义商品中,并以此作为人际社会身份的替代罢了。拥抱数字文本空间——它在上文语境中被视为媒介商品——将会把人封闭在自己的个人消费习惯“泡状空间”(bubble)当中。

从飛浩隆独创的动物化理论中可以看出:他笔下的主体与与东浩纪语境中“动物化的”、内向化(inward-turned)的御宅族主体截然不同;飛浩隆在讨论数字空间和数字主体时所使用的生态式语言风格,是一种抵抗资本主义对世界的超个人化(hyper-personalization)的方式:它倾向于对个体外部的事物采取一种以关系性为基础的建构方式。在描述《#银之匙》中使数字文本空间成为可能的通用网络基础设施的崛起时,叙述者向我们讲述了耐人寻味的实际情况:伴随着通用计算技术的初步推广,AR服务业进入了大众的视野,但AR最初的爆炸性增长,却成为了消费者所抵制的对象。叙述者解释道:

正因为用户可以设置自己的AR滤镜,街道才失去了它们的吸引力。街道,不是某人自己的房间,亦非供人休憩的小天地...它们,是人们狩猎的田野山丘。只要街景仍与众多个体的自主活动交织在一起,街道便是一种与山野别无二致的“自然”。在这种自然中,预料之外的他者应接不暇——街道的价值,就在于此。所以,用AR覆盖街道,就跟用自己的气味覆盖猎场一样愚蠢。如果你在田野中闻到的只有自己的气味的话,你又怎么能够嗅出猎物呢?[29]

飛浩隆的社会-本体论框架十分重视数字主体和人类主体之间的差异,但同时,它从未将等级关系强加于这些主体之上。正如我们所见,《自生之梦》中的文本成为了一种平行于客观世界存在的自然力量。但这并不是说文本与现实可以互换,也不是说飛浩隆对数字文本空间的想象就认定了它不会被类似“假如客观世界完全被机器取代”这样的事情所影响。例如,小说中的数字主体并不具备传达情感强度的能力,甚至无法理解其概念——这是因为,情感强度本质上是一种超出语言范畴的存在;相比之下,数字主体只能通过语言存在,而且,它的存在本质上是离身(disembodied)的。这一点在《#银之匙》的开场部分中显而易见;小说中,四岁大的杰克·沃恩的个人卡西代理端用他的语音讲述了这一部分的故事。起初,叙事(风格)尚且符合孩童的口吻:它所使用的,是仅由数个基础汉字字符构成的简单句法结构。然而,文本在杰克发脾气时变得愈加密集,而充斥其中的则是生硬的语句和晦涩难懂的汉字。杰克的卡西代理端无法准确地用孩童的口吻传达它对杰克高昂的情绪状态的主观体验,于是,卡西所使用的措辞便默认回退到了纯粹描述性的客观专业术语。[31] 这段情节表明:物质存在的某些部分,是数字存在所没有的。我们绝不可忽视物质与文本之间的差异,纵使它们都可以影响人类的主体生成。

尽管如此,飛浩隆的文本性模型仍为我们指出了一种更具创造性的接触文本的方式。《自生之梦》四部曲并没有将文本视作身为人类原初创造力的衍生物的记录档案,而是将其设想为一种能够塑造人的生成的积极力量。这种想象甚至延伸到了占据故事大部分篇幅的数字空间之外(的客观世界)。《#银之匙》中,文本与人类主体共同进行变革、共同进行个体化的能力在小说对爱丽丝·沃恩的母亲多莉丝的书法生涯的描写中得到了展现。当看到王羲之和张芝书法作品的复制品时,多莉丝第一次产生了学习书法的念头:「通过汉字那动态匀称的形体美,书法铿锵有力地传达了它的精气神。她对这一点印象深刻...」小说如是描述。[32] 书法,不单单是对先前作品情感(antecedent affects)的索引【译注5】,它还在书法家和书法作品共同参与的变革型创造力的具身过程(embodied process)【译注6】中发挥着文字记录、文化产品、和共同创作者的作用。多莉丝所在的产科病房房间里挂着的书法作品展示了「书法家在用毛笔写字时,所运用的笔触和起笔/运笔/收笔笔法,以及,书法家执笔时全身各个部分——从手部、臂部、肩部、躯干、一直到脚部——的发力。」[33] 换而言之,与非人主体的创造性合作并不局限于“爱丽丝和她的算法诗歌之间的合作”这一种;我们甚至可以在2世纪的中国书法家的作品中发现这种合作。

借《自生之梦》四部曲,飛浩隆鼓励我们在当下时分——目前,晚期资本主义社会似乎充斥着再塑人类存在的非人实体——重新评估非人文本的本体力量。从最初的机器人主题到现今的人工智能主题,日本和其他国家/地区的科幻作品在记录工商业资本所带来的科技进步的同时,亦对后者抱有一定程度的怀疑态度:这些作品对非人主体(agent)在人类生活中激起的变革保持着警惕。围绕着这些变革的妄想往往和顺性别异性恋父权制之间有着深层次的关联:这意味着,同样的改变在70年代的日本女性主义科幻小说中可能会被认为是拯救性的(salvific),但是,在科学幻想这个传统上由男性作家的意见主导话语的作品流派中,非人他者受到如此的敌视也就不足为奇了。为回击这种“反动力量”,作者想要进一步拓展杜马斯对《自生之梦》的解读。她用东浩纪的数据库和宏大叙事理论来解读忌字祸,并认为忌字祸拥有“有异于算法诗歌的”(heteropoeitic)潜能,一种完全蛰伏着的、等待着人类主体的认知的潜能。[34] 在作者看来,我们也可以这样理解《自生之梦》的文本:它将数据库自身转变成了一个积极、能动的主体,后者与人类的主体性相互构成,但又有着根本上的不同。简而言之,飛浩隆提出的问题是:我们应该如何与书写自身的数字主体建立关联?

我们总是与主观视野之外的事物(包括语言自身)进行着生动的交流,即使我们并没有认识到这种交流(的存在)。飛浩隆便是通过向读者展示这一点,从而避免了和非人事物的对立。在形式上,《自生之梦》和它的三部外传展现了这种与非人事物的接触;这几篇小说对自身的定位是:被互文引用的算法过程所自动生成的文本。为了明确表示读者手中捧着的是由卡西代理端所生成的文本而使用“#”号标记自然段开头的文体特征、以及叙述者自己将文本描述成“与GEB进行算法交互后的产物”的习惯,都是将文本同时定位为叙境物(diegetic)和非叙境物的策略;它混淆了虚构设定和读者所处现实世界之间的鸿沟。具体而言,《自生之梦》那鲜明的指涉性——包括从《白鲸记》到《蜂巢幽灵》(西语原文为El espíritu de la colmena,维克托·埃里塞 [Victor Erice] 导演,1973年上映)到《沉默的羔羊》的一系列引用——进一步强调了“小说文本是由作为其叙述对象的文本间运动所生成”的这一事实。飛浩隆暗示:“自生之梦”的故事碎片早就在它的源文本中一直蛰伏着,并且只需在创造性个体化的过程中被聚合在一起即可现形,就像过饱和溶液中等待刺激以析出的晶体那样。因此可见,人的创造力总是延伸至人的外部、延伸到了创造行为中所使用的那些不属于人类的灵感和指涉物那儿,而《自生之梦》则鼓励着读者去关注他们自己的——超越人类的合作。

译注

1. 译文中的《自生之梦》人名、专有名词以及选段均参照自丁丁虫(丁子承)翻译版本。

2. 另请参见蒸汽波风格。

3. 节标题的英文原文为“Nature Read in Tooth and Claw”,化用自丁尼生的诗句「Tho’ Nature, red in tooth and claw」.

4. 译文中的《神经漫游者》人名、专有名词以及选段均参照自Denovo(徐海燕)译本。

5. 指临摹著名的书法作品,并试着传达原件的灵性、精气神、情感基调...等等。

6. 这对于书法作品来说是“创新”,而对于书法家来说则是“悟道”。

附录

1. J·G·巴拉德:<哪条路通往内部空间?>(Which Way to Inner Space?),《新世界科幻》(New Worlds Science Fiction),第118期(1962年5月),页128.

2. (英文原文中)对《自生之梦》的所有摘抄均援引自吉姆·哈伯特(Jim Hubbert)2012年的翻译版本(详见附录5);所有对四部曲其他三篇小说的(英文)引用则是由作者原创翻译而成。

3. (在英文原文中)为保持一致,作者在文中保留了飛浩隆对卡西的罗马化处理“Cassy”,而不是哈伯特全部大写处理的“CASSY”。

4. 蕾切尔·杜马斯:<飛浩隆‘自生之梦’中的病毒作用和欲望经济学>(Viral Affects and Economies of Desire in Hirotaka Tobi’s ‘Autogenic Dreaming,’),《推断》(Extrapolation),第60卷,第1期(2019年4月),页24.

5. 飛浩隆:<Autogenic Dreaming: Interview with the Column of Clouds>,《日本未来时》(The Future is Japanese),吉姆·哈伯特英译,旧金山:Haikasoru出版社,2012年,页321.

6. 路易·阿尔都塞:<意识形态和意识形态国家机器:研究笔记>,《列宁和哲学及其他论文》,本·布鲁斯特(Ben Brewster)英译,纽约:每月评论出版社(Monthly Review Press),2001年,页85-126.

7. 参见飛浩隆,<Autogenic Dreaming>,页351.

8. 参见杜马斯,<病毒作用>,页37.

9. 参见飛浩隆,<Autogenic Dreaming>,页364.

10. 飛浩隆:《自生の夢》,东京:河出書房新社,2016年,页222.

11. 参见飛浩隆,《自生の夢》,页224.

12. 参见飛浩隆,《自生の夢》,页229.

13. 参见飛浩隆,《自生の夢》,页106.

14. 托马斯·拉马尔:《动画机器:动画的媒体理论》,明尼阿波利斯:明尼苏达大学出版社,2009年,页xxx-xxxiii.

15. 参见飛浩隆,<Autogenic Dreaming>,页349,加粗部分为作者强调之。

16. 参见飛浩隆,《自生の夢》,页226.

17. 威廉·吉布森:《神经漫游者》,纽约:王牌书社(Ace Books),1984年,页51,加粗部分为作者强调之。

18. 参见吉布森,《神经漫游者》,页52.

19. 参见飛浩隆,《自生の夢》,页223.

20. 参见飛浩隆,《自生の夢》,页223.

21. 参见飛浩隆,《自生の夢》,页224.

22. 参见飛浩隆,<Autogenic Dreaming>,页362.

23. 参见飛浩隆,<Autogenic Dreaming>,页360.

24. 参见飛浩隆,《自生の夢》,页231,加粗部分为作者强调之。

25. 斯科特·布卡特曼(Scott Bukatman):《终端身份:后现代科幻作品中的虚拟主体》(Terminal Identity: The Virtual Subject in Postmodern Science Fiction),达勒姆:杜克大学出版社,1993年.

26. 马克·斯坦伯格(Marc Steinberg):《日本动画的媒介交混:在日本进行玩具和角色的特许经营》(Anime’s Media Mix: Franchising Toys and Characters in Japan),明尼阿波利斯:明尼苏达大学出版社,2012年,页167-168.

27. 斋藤环:《战斗美少女的精神分析》,基斯·文森特、唐·劳森(Dawn Lawson)英译,明尼阿波利斯:明尼苏达大学出版社,2011年,页xv.

28. 东浩纪:《动物化的后现代:御宅族如何影响日本社会》(英译名为Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals),乔纳森·E·亚伯(Jonathan E. Abel)、河野至恩英译,明尼阿波利斯:明尼苏达大学出版社,2009年,页25-95.

29. 参见飛浩隆,《自生の夢》,页101.

30. 参见拉马尔,《动画机器》,页45-54.

31. 参见飛浩隆,《自生の夢》,页96-98.

32. 参见飛浩隆,《自生の夢》,页103.

33. 参见飛浩隆,《自生の夢》,页104.

34. 参见杜马斯,<病毒作用>,页34-37.

作者介绍

截止发稿时,布莱恩·怀特是卡拉马祖学院(Kalamazoo College)日语系的一位助教授。他的研究探讨了当代日本媒介文化和身份建构。目前,他正着手于一个研究二十世纪六十年代日本的科幻媒介生态和社区形成的学术项目。

The cover image for Tobi Hirotaka’s 2016 collection of short stories Jisei no Yume (Autogenic Dreaming) by illustrator agoera features a female figure standing on a bleached, blasted plain (Figure 1). She faces away from the viewer, gazing at the far horizon and the massive white whale that floats above it in front of an orange-tinged sky. Like many science fiction illustrations, this one captures its viewer’s interest with a surreal space; spaces of all kinds have indeed been a consistent concern of science fiction from its early days. J. G. Ballard famously characterized the New Wave movement in science fiction (SF) as being marked by a shift in interest from outer space to inner space, from neocolonialist narratives of exoplanetary exploration and conquest to more existentialist concerns of the individual subject and its everyday life under conditions of postmodern capital. [1] Cyberpunk fiction, in turn, thematized the digital environs of cyberspace, endowing proliferating computer technologies with an interior expansiveness through which digitized human consciousness could move. Science fiction’s spaces are the milieux through which its subjects are defined, be it through the extraterrestrial or digital colonial frontiers of Golden Age SF and cyberpunk, the coercive systems of postmodern paranoia in New Wave SF, or the hardscrabble state of nature of post-apocalypse narratives.

As the cover image signals, Tobi’s short stories, too, take space as an organizing concern. What I will be terming the “Autogenic Dreaming” tetralogy consists of a novelette and three accompanying short stories, first published between 2009 and 2015. The first, the eponymous “Autogenic Dreaming,” garnered immediate acclaim, winning Tobi the 2010 Seiun Award, one of the two biggest SF awards in Japan, for Best Short Story. [2] The four texts that make up the tetralogy each provide a different vignette surrounding the central motif of the digital space that serves as the setting for “Autogenic Dreaming”— what Tobi calls “digital textspace” (denshiteki moji kūkan)— as well as the entities that traverse and inhabit it. Tobi’s attention is focused almost entirely on issues of digital ontology, asking what the nature of being and becoming is in an entirely digital realm. Tobi’s uniquely ecological approach to questions of digital space and digital life point the way toward new understandings of subjectivity in digital society.

Dreaming Up Textspace

“Autogenic Dreaming” was the earliest published story in the tetralogy, but narratively comes third in the events depicted. Its three companion pieces each explore further the implications of digital space and digital life through vignettes surrounding the life and death of one of its protagonists, the brilliant digital poet Alice Wong. In so doing, they add more fine-grained nuance to the “Autogenic Dreaming” model of digital textspace and the nonhuman subjects within it. The narratively earliest story, “#ginnosaji” (#silverspoon, 2012), details the invention of Cassys — algorithmic AI text programs — by the newborn Alice’s father, Richard, and the universal computing and network infrastructures that enable them. “Kōya ni te” (In the wastes, 2012) picks up five years later at a children’s camp where young Alice and her friend Katsuya play games with their Cassys and experiment with the kinds of creative generation that are possible with the digital agents. They demonstrate the potential of the Cassys to be more than simple information retrieval and reference tools, in particular their capacity to collaborate with their human users in a mode of collective artistic practice. “Yasei no shisō” (The savage expression, 2015, a reference to Mizumi Ryō’s 1982 short story “Yasei no yume”) skips ahead to a few years after the events of “Autogenic Dreaming” and Alice’s death, to find her friend Katsuya and her brother Jack working to contain destructive “stray poems” that Alice left as part of an unfinished project in digital space, and which now pose a threat to other users. The story outlines the transformations Alice envisioned for digital textspace and the implications they held for digital subjects. The arc of the tetralogy overall tracks the evolution of textspace and Cassy AI agents toward an increasingly independent form of existence.

Digital space in “Autogenic Dreaming” is both setting and character for the narrative. The novelette tells the story of a massive digital archive called GEB (Godel’s Entangled Bookshelf), which is analogous to Jorge Luis Borges’s Total Library, containing not only every document ever recorded by human civilization but also copies of all those documents translated into every language ever spoken and then tagged, indexed, cross-referenced, and linked to one another to create a whole that is far more than the sum of its parts. GEB is under attack from a virus named Imajika, and the narrative of “Autogenic Dreaming” follows the fight against it as narrated by a number of “Cassys” [3] (Complex Adaptive Systems), which are explained as AI-based “textual agents” that maintain GEB and run search queries of it. The Cassys have created digital reincarnations of the author-cum-serial killer Mamiya Jundo, and of Alice Wong, and through them the Cassys hope to contain the threat posed by Imajika to GEB. As the narrative explains, all of these textual operations are what allow the story to appear in front of the reader in concrete form; the narrative world and its protagonists only exist as data that have been compiled from within GEB.

Natural Language

The ontological questions posed by the Autogenic Dreaming tetralogy — that is, what is the nature of digital life-forms, and how can we best relate to them — immediately encounter the issue of text. Given that digital “spaces” like cyberspace are in fact simply visualizations and models created through the parsing of textual computer code; any consideration of digital life must take into account text and language as fundamental ontological components of the subjectivity thus constructed. As such, Tobi confronts the reader with the question of how digital life, insofar as it takes shape through hegemonic codes of linguistic expression, might nevertheless exceed hegemonic models of subjectivity and generate unexpected or novel new formations. As Raechel Dumas puts it, “Tobi takes the theoretically limitless domain of cyberspace as a vehicle for exploring the manner in which language at once arises out of and generates lines of escape from existing systems of representation.” [4] The importance of Tobi’s choice of name for “digital textspace” begins to come into view here, but one more step is needed to capture the full significance of this terminological shift.

Within the “Autogenic Dreaming” series of stories, the text itself, as it is being read by the reader, becomes implicated with digital textspace. This is reflected formally in part by the story’s highly referential nature. We have already seen the allusions to Moby-Dick, but the novelette deals in a whole catalog of allusions from Silence of the Lambs to Spirit of the Beehive. Additionally, through multiple direct addresses to the reader and self-aware references to the textual form it takes, the tetralogy breaks open the sealed fictional world of its setting and expands its concerns with nonhuman spaces and beings into the lived world of the reader. Rather than an imagination of artificial life that is contained to the ahistorical future of sci-fi, Tobi’s texts spur us to consider their relevance to the immediate, worldly present.

What, then, does Tobi’s theory of digital life forms entail? Let us return once more to the cover illustration of the Autogenic Dreaming collection. The illustration does not make use of the common visual vocabulary of digital spaces as popularized by cyberpunk in the 1980s and 1990s; we do not see a Cartesian grid overlaid on an infinite, featureless field, nor do we see floating lines of text and code nor sleekly streamlined abstract shapes and solids. Rather, this depiction of textspace (as the short stories will reveal it to be) appears as a natural, if desolate and surreal, space complete with recognizably human and animal figures. The rough brushstrokes agoera employs to illustrate the scene give it a rugged, unpolished look at odds with conventional images of digital space, more like a boulder than a sleek spaceship. Textspace in Tobi’s tetralogy represents an ecologically inflected rethinking of digital space and nonhuman life that explores the lively, active role that text can play in communal becoming and individual subjectivity. As we will see, Autogenic Dreaming breaks down the binary of nature and (digital) culture by insisting that each is shaped by the other and that both shape our subjective engagements with the world; it pushes the reader to turn out toward the spaces of contingent communal living, receptive to the human, digital, and natural voices that comingle there.

Searching To Be

The dialogic process of search queries and results is literally the act of becoming within the world of “Autogenic Dreaming.” One passage near the beginning of “Autogenic Dreaming” makes this clear when it states, “This story — leaving aside the question of whether this is in fact a story — is the record of an extended interview. . . . The interview was also, in and of itself, the struggle with Imajika.” [5] Put another way, in this story, language and action are considered equivalent. The main characters that are compiled by the Cassys are digital reincarnations of the young wunderkind poet Alice Wong, and the prolific author and serial killer Mamiya Jundo. Their very existence, as well as their actions within the text, are based on the Cassys asking questions of GEB, searching its databases for the writings of Alice and Mamiya and other related texts, and compiling and outputting the answers. In other words, there is no essential interiority to these subjects; their ontology is entirely relational, built out of thousands of connections between and among textual data, and existing only as the textual product being read by the story’s audience. The retrieval and activation of these connections is what enables the becoming of Alice Wong and Mamiya Jundo as they appear in the text. Their subjective actualization is thanks entirely to retrieving archival data and uncovering archival relations.

The call-and-response (or, perhaps better, search-and-output) ontological model behind Alice and Mamiya’s existence bears some structural similarity to Louis Althusser’s theory of the interpellation of subjects by ideology as part of the Ideological State Apparatuses (ISAs) that perpetuate the division of labor in capitalist class societies. [6] In one scene, Mamiya asks the Cassy writing him where the “wellspring” of his existence is located. The Cassy responds by saying that they are compiling “tens of thousands of Jundo Mamiyas” [7] by initiating a multitude of search queries within the GEB database, each related in some way to Mamiya’s life and writerly output. Just as the ideology of the ruling classes transforms individuals into subjects through an act of hailing, and subordinates them to the state apparatus of power, we could read the Cassys as literally inscribing Mamiya as Mamiya (writing him as a subject) in the service of GEB through an act of searching the archives related to his life and writings. The subject for Althusser is always a subject in a hierarchical relationship of power with the state, and Mamiya here is similarly only Mamiya insofar as he exists through and in service to GEB. Just as Ideological State Apparatuses hail the individual as a subject in order to reproduce of the conditions of production that sustain the state apparatus, the Cassys compile Mamiya from the database so that he will defeat Imajika and reinscribe GEB’s status quo.

Imajika poses a threat to GEB in “Autogenic Dreaming” precisely because it introduces unquantifiable relationships within language, twisting and mutating the archive in horrifically bodily ways that exceed neat representation. The digital manifestations of texts bloat grotesquely as words multiply, intermingle, merge, divide, and spill outside of the bounds of the text. In other words, it prompts new textual — and therefore subjective — becomings by altering the relationships between texts that serve as the ontological basis of the characters that appear within digital textspace. Dumas offers a compelling reading of Imajika as representing inexpressible trauma related to sexual difference, positioning the virus finally, “not as a gesture toward the death of meaning, but as a site where that which eludes representation is nevertheless registered as heterogeneous code.” [8] While not disputing Dumas’s interpretation, I nevertheless would like to suggest that Imajika, as well as providing a psychoanalytic lens for the individual subject, serves as a site of negotiation for intersubjective (that is, social) transactions. Texts and intertextual relations are therefore not only a means for digital life forms to express themselves, but the very grounds of their being.

The texts begin to diverge from the overdetermined class subjects of Althusser in that digital beings’ relationships necessarily carry with them a measure of underdetermination. The Cassys that narrate the story assert that, despite its thorough cataloging and quantification, GEB is essentially unknowable in toto. Complete knowledge of this type — that is, an overdetermined quantification of every aspect of someone or something — is associated with the death of the subject in question. This is how Mamiya Jundo was able to kill his dozens of victims: he is described as having a supernatural ability to create a complete psychological profile of an individual based on any small detail related to them. By talking to that individual, he is then able to implant this knowledge into his victim, such that they are completely and utterly known to themselves. With no part of themselves remaining underdetermined and open to change and transformation, “The psychic structure collapses completely,” [9] and the victim commits suicide. Thus, while a massive digital archive like GEB might initially appear to point toward panoptic surveillance and complete, overdetermined knowledge of the subjects contained therein, the characterization of Mamiya’s profiling ability demonstrates that any kind of lively activity — in textspace and beyond it — is reliant upon an element of not-yet-knowing that must be discovered in moments of intersubjective contact.

Tobi’s model of subjectivity is one that turns his characters outward, consistently searching out new and unexpected connections and transformations. The Cassys become active collaborators in this process, extending subjects like Alice beyond their own bodily capabilities and affording them new modes of expression. We see an illustrative example of this during a flashback sequence in “The Savage Expression.” In this scene, a ten-year-old Alice is demonstrating her latest “poem” to an audience of family, friends, and fans. The poem is in actuality a complex AI program visualized in augmented reality as a “poetical beast,” a creature Tobi likens to Dutch artist Theo Jansen’s “Strandbeest” kinetic sculptures, which are assemblages of wood and sails that catch the wind in order to move the sculpture’s legs and cause it to walk. [10] In Alice’s poem’s case, it is textual production that provides the motive force for her poetical beast to move. Her imbrication with the Cassys that are running the program is revealed in part when the narrator says, “With the support of her Cassy, Alice spoke in a grown-up fashion.” [11] With this, Tobi implies that Alice’s ability to express herself as a mature artist — her identity as a mature artist — is dependent in part on her Cassys. Without the textual agents, Alice cannot become Alice as the reader knows her.

More than being an expressive supplement or prosthetic for an immature subject not yet fully in command of her own linguistic faculties — that is, rather than being subsidiary to the “original” or “authentic” Alice-as-independent-artist — the Cassys are understood as partners in the expressive act. As Alice explains to her audience that it is the energy contained in the moment of encounter between poem and reader that powers the ongoing becoming of the poetical beast, a critic in attendance reacts by saying, “I see . . . This thing is a ‘movement.’” The narrator goes on to elaborate: “It wasn’t a standalone poem. Nor was it a poetry collection. The beast’s form and behavior were animated by the sudden rise of a literary movement— a ‘movement’ ignited by a single poem that caught hold of a multitude of poets.” [12] The Cassy AIs here react to each other’s output, and their behavior comes to resemble an active community of artists consuming each other’s work and producing pieces in response. After Alice sets the initial parameters, they act almost entirely independently. More than tools of a master artist, the Cassys with which Alice works in her poetic practice are artistic collaborators.

This echoes a scene in “In the Wastes” in which Alice and Katsuya are playing with their Cassys. In the story’s chronological predecessor, “#silverspoon,” Cassys were essentially automated Twitter accounts, following a user through the global data infrastructure and logging their activities, cross-referenced with a host of data gathered from the network, and outputting text in the user’s own voice back into the network. Hence, when they are first introduced in “#silverspoon,” they are referred to as “life-log secretaries” (raifurogu shoki), [13] and they are frequently described as “secretaries” thereafter, implying a derivative relationship to originary, ontologically antecedent humans. In “In the Wastes,” however, Alice and Katsuya play with the Cassys’ ability to act dynamically and autonomously by creating algorithms through which the Cassys assemble fantastical scenes in augmented reality for the children’s amusement. Once again, Alice’s handling of the Cassys is marked by artistic equality, such that the AI agents are able to dynamically evolve the ways they search out and absorb information above and beyond any specific instructions given by Alice herself. Whereas Katsuya is likened to a master artist using a multitude of tools, Alice is more akin to a member of an artists’ collective, the AIs her fellow creators.

Nature Read in Tooth and Claw

The centrifugal motion of subjectivity in the “Autogenic Dreaming” tetralogy, in which subjective identity moves outward from the physical being to encompass and collaborate with that which is beyond it, is mirrored in and dependent upon the particular relationship to computing and digital space described in Tobi’s works, which are in turn mirrored by the works’ own place within a digitally saturated historical moment in Japan. Tobi’s stories “think technology,” [14] especially computing technology, in subtly — but crucially — different ways than many of their cyberpunk and New Wave predecessors. In doing so, Tobi outlines a subjectivity under high-tech capitalist conditions that is not just individual, but social.

In considering the Cassy agents in “Autogenic Dreaming,” we must keep in mind their connection to GEB and “digital textspace.” The space serves as an illuminating contrast with canonical imaginations of digital environments, breaking from the sleekly (post)modern techno-fetishism of cyberpunk, the science fiction movement most closely associated with the idea of cyberspace. In it, we can find productive resonances with the critical posthumanist scholarship that arose to grapple with the themes of cyberpunk, the language of which provides useful starting points from which to approach Tobi’s works. The language Tobi uses to describe the digital environment of textspace and the massive textual archive that it houses, GEB, while overlapping with critical posthumanism, nevertheless exceeds total capture within that theoretical framework.

The Cassys who narrate “Autogenic Dreaming” inform us that GEB exceeds any human’s ability to completely grasp it in exhaustive detail. Their choice of words, however, is intriguing: “GEB is a gigantic synthesis of meaning, mentation, and correspondences that far exceed anyone’s comprehension,” the narrator states. “It’s almost as if another natural world has come into being.” [15] This choice to consider GEB in naturalistic terms is repeated throughout the tetralogy with regard to both GEB and digital textspace more broadly, signaling an ongoing concern for Tobi. In “The Savage Expression,” for instance, during Alice’s poetry demonstration, she presents her audience with a visualization of the algorithmic backstage — what she terms “poésispace” — underpinning the transformations of her poetical beast. It is described as a place where, “Texts new and old from all corners of the world floated about equally, and countless digital agents moved about in the textual sedimentation, digging it up, cutting it apart, pasting it together, knotting it up, and birthing yet more texts. It was like the soft soil of words, sheltering many microbes and earthworms.” [16] Digital space in Tobi’s works, as we can see here, is a much earthier place than in much of conventional science fiction.

As epitomized by cyberspace in William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984), digital space to science fiction is often conceived as an illusion of space existing as a “consensual hallucination” within the user’s own mind, “A graphic representation of data abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system. . . . Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding.” [17] Digital space here is radically introverted, despite its highly networked nature. What is more, it exists as an abstraction of data, that is, an abstraction of an abstraction two degrees removed from a presumably authentic physical reality. The subjective experience of cyberspace by Gibson’s protagonist, Case, reads similarly: “fluid neon origami trick, the unfolding of his distanceless home, his country, transparent 3D chessboard extending to infinity. Inner eye opening to the stepped scarlet pyramid of the Eastern Seaboard Fission Authority burning beyond the green cubes of Mitsubishi Bank of America, and high and very far away he saw the spiral arms of military systems, forever beyond his reach.” [18] Again, the analogies by which cyberspace is visualized are not only exclusively geometric and artificial (stepped pyramids, green cubes, infinite gridded space), but intensely personal (his home, his country) and simultaneously corporatized. If digital textspace for Tobi is a parallel natural world, cyberspace for Gibson is literally parceled up according to capitalist logics of property and access.

Albeit in a way more reminiscent of evolutionary niches than Gibson’s gated communities, the introduction of “poésispace” in the scene above further subdivides Tobi’s model of the digital world. In effect, digital space becomes an umbrella term encompassing two distinct, yet connected, realms: digital textspace and poésispace. The former, as we have seen, is the realm of GEB, Cassys, poetical beasts, and all of the other algorithmic, textual subjects discussed thus far. Textspace is where texts and their relationships with one-another are already individuated, already given a stable ontological basis from which recognizable subjects — Alice, Mamiya, a poetical beast — can be identified. Poésispace, on the other hand, is, “the restless state before a poem becomes words,” [19] a pre-linguistic, protean space largely similar to the human creative process. The narrator of “The Savage Expression” describes it as follows:

Mosquito swarms of text (moji) formed innumerable spheres floating in a vast space. The masses expanded and contracted as if breathing, floated about, rotated, and moved up and down, back and forth, left and right. . . . Occasionally one mass would draw another in and swallow it up. Sometimes they would also excrete. [20]

The use of “moji” here, a more literal translation of which would be “written characters,” signals that these amoeba-like entities are not meaningful texts with established relational identities so much as simple conglomerations of randomly assembled characters from which relations might emerge and individuation might occur.

As Alice shows her audience the moment when raw text begins to individuate into a poem, Tobi’s use of naturalistic language persists, first in the register of microbiology, and then shifting to geology: “Like cell walls being dissolved in a base liquid, the boundaries of the text spheres all broke down at once. . . . Out of the textual mire, a meaningful form began to take shape, similar to how a crystal precipitates the moment a supersaturated solution receives a stimulus.” [21] Here, we see the birth of an entirely new digital subject from the textual profusion of poésispace, but as noted above, subjects in digital textspace continue to be animated by the chaotic underdetermination of poésispace. While textspace is the main setting and object of the tetralogy’s attention, thanks to its recognizable subjects who take meaningful actions, the unpredictable force of intertextual relationality that poésispace generates lies just beneath its surface and is a crucial component by which textspace is able to exist at all, just as microbes invisible to the human eye provide the engine by which the natural world as we see it is able to go on living.

With this in mind, we can understand Imajika’s mutations of the textual archive of GEB more fully. Near the end of “Autogenic Dreaming,” the digital reincarnation of Alice, standing in front of a petrified Imajika that has taken the form of the great white whale Moby Dick, ruminates on its nature. She intuits that Imajika is composed of all the relationships between texts that GEB could not classify, stating, “GEB couldn’t deal with these relationships because there was no way to assign them names. . . . GEB discarded millions and millions of these relationships . . . until they returned, bringing a dynamic system with them. Imajika . . . Without names, they are outside the “written” domain. The only alphabet that can write them is the wind.’” [22] Imajika is precisely the pre-individuated stuff of poésispace extruding into the individuated sphere of textspace. It is pure creativity, pure relationality, manifesting only through relations with other texts, that is, only through its effects on them, just as the wind is only visible through its effects on other objects.

Mamiya Jundo’s ability to overdetermine an individual through his capacity to create full psychological profiles of them is thus positioned as Imajika’s inverse. Imajika appears petrified in this scene because Mamiya has made it completely known to itself, quantified and overdetermined with no possibility of transformation, just as he did to his human victims in life. This resolution is echoed in “The Savage Expression” when Jack Wong and Alice’s childhood friend Katsuya stop the dangerous stray poetical beast, not by destroying it, but by freezing it in a sort of suspended animation. Stasis marks the resolution to these conflicts, as well as textspace itself; the settings of both of these scenes are described as similar to salt flats — a dead and sterile environment. Despite the dynamism of many of the subjects found there, digital textspace itself remains somewhat lifeless.

And yet, Imajika and the poetical beast point toward an evolution of textspace that seems inevitable. Even in spite of Mamiya’s containment of Imajika, the virus’s fundamental nature as change itself suggests that it will eventually break its containment. The narrator in “Autogenic Dreaming” even tells us, “Imajika might burst its bonds and run amok again at any moment.” [23] Transformation, it seems, cannot be stopped in textspace, and neither Alice nor Mamiya seem particularly concerned to do so. The two speculate that they themselves were probably compiled by GEB because the database hopes to harvest the “whale oil” contained within Imajika. In other words, it hopes to use the creative force Imajika embodies to power further expansions and developments of the archive, just as the whaling industry helped fuel the Industrial Revolution in the West. However, Alice and Mamiya seem to understand that it is a different kind of transformation that is needed, one more in keeping with the nature of Imajika and digital space as Tobi has constructed it.

Alice herself provides an alternative, ecological model of the transformation of digital textspace in “The Savage Expression.” We learn that, at the time of her death, Alice had been in the midst of a massive new poetry project aimed at incorporating climatological and earth science simulations into her works in digital textspace; with the eventual goal of creating a complete and independent ecosystem in textspace, where her poetical birds and beasts could live, thrive, and presumably reproduce. She had hoped to create a self-generating (autogenic) environment for her creations: “Not heaven and earth as described by poems,” the narrator clarifies, “Rather, all the physical and chemical reactions that occur in the world would be made out of ‘just a poem,’ a poem written down in text. A world in which all of creation would be a single poem.” [24] Whereas GEB seeks to compartmentalize and harness the creative energies of poesispace, Alice hoped to set those energies loose on textspace itself, transforming it like the natural phenomena that shape our own world. With her project cut short by her death, however, whether such a transformation will come about remains an open question, one that Tobi’s tetralogy implicitly poses to the reader.

Writing With The Wind

The shift from cyberpunk literature to “Autogenic Dreaming” mirrors the shift (both in the texts and in society) from a “terminal” [25] internet — that is, one accessed only through discrete, stationary computer terminals — to a mobile, distributed, and ubiquitous network infrastructure, accessed from a variety of devices. Network technologies and human interactions with digital networks, in other words, have become more ambient, part of the lived environment of the everyday as opposed to the addictive, pathological relationship seen in, for instance, Neuromancer. In contemporary Japanese popular culture, especially, this expansion has been discussed in terms of the expanding reach of capital and the interweaving of consumer practices with personal identity. The “endo-colonization” [26] of the consumer subject’s everyday by media products, the parallel of digital textspace’s spread of textuality into the milieu of universal computing infrastructures, appears ineluctably bound up with postmodern late capital: it seems to invite the personalization, privatization, and monetization of space, eroding the commons in favor of a solipsistic, intensely personalized consumer experience of contemporary living. To the extent that resistance is possible, it is achieved only by taking subjective value from media texts, in spite of their imbrication in systems of consumption.

This sort of unique parasocial relationship with fictional texts is frequently identified as a salient feature of otaku consumers, making them ambivalent subjects of resistance to capitalist logic and, simultaneously, the apotheosis of subjectivity qua consumerism. Saitō Tamaki has defined otaku as, in the words of J. Keith Vincent’s translated introduction, subjects “distinguished . . . by their ability to take pleasure in multiple levels of fictionality and to recognize that everyday reality itself is a kind of fiction,” [27] while Azuma Hiroki notes the deep “database” structure of recombinant aesthetic elements that compose otaku media and also serve as the object of otaku consumption. [28] Social anxieties surrounding the figure of the otaku conflate a heightened awareness of the subject’s connection to textuality with a decline in interpersonal relations. To wit: serious engagement with the texts that saturate the sphere of everyday human activity is in fact simply the act of immersing oneself in capitalist commodities as a substitute for interpersonal social identity. Embracing digital textspace — here figured as media commodities — seals one off in one’s own personal “bubble” of consumer habits.

Tobi pushes against Azuma’s “animalized,” inward-turned otaku subject with an animalization of his own; his ecological language in discussing digital spaces and subjects is a way of pushing against capitalist hyper-personalization of the world in favor of a fundamentally relational approach to that which is outside the individual subject. In describing the rise of the universal network infrastructure that enables digital textspace in “#silverspoon,” the narrator gives us the interesting fact that the initial explosion of augmented reality services that had accompanied universal computing’s initial rollout actually became the target of consumer pushback. The narrator explains:

Precisely because the users could set their own filters, the streets lost their appeal. The streets are not one’s own room. They’re not a burrow where one goes to sleep, they’re the hills and fields where one hunts game. Insofar as the scenery of the streets weaves together with the autonomous activities of many individuals, they are a type of “nature” no different from the hills and fields. An inundation of others who don’t conform to your expectations. The value of the streets is found precisely here. Overlaying them with AR is the same folly as smothering the hunting grounds in your own odor. How are you supposed to sniff out game if all you can smell in the fields is your own scent? [29]

Here, Tobi makes the case that urban space must be a site of communal social activity, that individual subjects must remain open on some level to the unexpected actions of others, just as unexpected intertextual connections fuel the movements of Alice Wong’s poetical beast. Increased engagement with that which is outside oneself, whether digital text or natural being, is meant not to force that other to conform to an overdetermined role, but to provoke creative transformations in both parties. Digital sociality in “Autogenic Dreaming” is fundamentally anti-instrumental in its logic, with each individual subject collaborating with others, not to turn them toward a use or make them into a “merely technological” [30] solution to a problem, but to simply discover where such collaboration might lead and how the subject will change as a result.

Tobi’s social-ontological framework takes seriously the differences between digital and human subjects without ever imposing a hierarchical relation upon them. As we have seen, text in “Autogenic Dreaming” becomes a natural force that exists in parallel to the physical world. This is not to say that the two are interchangeable, nor that Tobi’s imagination of digital textspace presumes that it would be unaffected if, say, the physical world were replaced entirely with machines. For example, we see that digital subjects, being fundamentally disembodied and existing only through language, do not have the ability to communicate (or perhaps even understand) affective intensities that exceed language by nature. This is evident in the opening pages of “#silverspoon,” which are narrated by four-year-old Jack Wong’s personal Cassy in his voice. Initially, the narration befits a young child, using simplistic sentence structures, and with only a few basic kanji characters. When Jack throws a temper tantrum, however, the text becomes more and more dense with difficult kanji and terse turns of phrase. Unable to accurately communicate the subjective experience of Jack’s heightened affective state in the language of a child, his Cassy defaults back to simply descriptive, objective technical language. [31] This episode demonstrates that there are some facets of physical existence that have no equivalent in digital being. While both the physical and the textual can influence human subjective becoming, the differences between the two should not be understood as inconsequential.

Nevertheless, Tobi’s model of textuality points us toward a more creative engagement with it. The tetralogy imagines text as an active force shaping human becoming, instead of as a record that is derivative of original human creativity, and this extends even outside the digital spaces that occupy the bulk of the narratives. The capacity of text to afford mutual transformation and mutual individuation with a human subject is on display in the “#silverspoon” description of Alice Wong’s mother Doris’s career as a calligrapher. We are told that she was first inspired to take up calligraphy when, upon viewing reproductions of calligraphy by Wang Xizhi and Zhang Zhi, she was, “deeply impressed at how the spiritual was so strongly conveyed through the dynamic, well-proportioned beauty of the shapes.” [32] More than simply indexing antecedent affects, the calligraphy serves as record, product, and co-creator in an embodied process of transformative creativity together with the calligrapher. The calligraphy on display in Doris’s room in the maternity ward embodies, “the bounding reaches, strokes, and movements that the calligrapher had invested in the brush from the hand, arm, shoulder, torso, all the way to the feet.” [33] Creative collaboration with nonhuman subjects, in other words, is not limited to Alice’s algorithmic poems, but can be found even in the works of second century Chinese calligraphers.

With the “Autogenic Dreaming” tetralogy, Tobi encourages us to reevaluate the ontological force of nonhuman texts at a moment when late capitalist society seems to overflow with nonhuman entities reshaping the human being. Science fiction, in Japan as elsewhere, has registered the progress of the technologies of industrial and commercial capital — first in the guise of robots, and then as artificial intelligences — with a measure of suspicion, wary of the transformations in human living that these nonhuman agents were recognized to incite. The paranoia surrounding these transformations was often deeply implicated with cisgender heterosexual patriarchy, meaning the same changes might be received as salvific in Japanese feminist science fiction in the 1970s and after, but in a genre whose discourses have classically been dominated by the voices of male writers, it is little surprise that the nonhuman other has been met with such hostility. In pushing back against this reactionary impulse, I would like to extend Dumas’s interpretation of “Autogenic Dreaming,” which reads Imajika with Azuma’s theory of the database and the grand nonnarrative, the “heteropoeitic” potential of which is fundamentally latent and waiting to be recognized by the human subject. [34] In my view, the “Autogenic Dreaming” texts can also be seen as making the database itself into an active, agentive subject that is mutually constitutive of, but radically different from, human subjectivity. Tobi asks, in short, how we can relate to a digital subject that writes itself.

Tobi Hirotaka circumvents antagonistic confrontation with the nonhuman by showing us how we have always had lively intercourse with that which is outside our subjective horizons — including language itself — even if we did not acknowledge it. “Autogenic Dreaming” and its three companion pieces stage this nonhuman encounter in their very form, positioning themselves as automatically generated by algorithmic processes of intertextual citation. The stylistic feature of marking paragraphs with “#” to explicitly flag the idea that the text in the reader’s hands was produced by Cassys, as well as the narrator’s own habit of characterizing the text as the output of algorithmic interactions with GEB, are both strategies that position the text as simultaneously diegetic and nondiegetic, muddying the divide between fictional setting and the lived world of the reader. The explicitly referential nature of “Autogenic Dreaming,” in particular — with citations ranging from Moby-Dick to Spirit of the Beehive (El espíritu de la colmena, Victor Erice dir., 1973) to Silence of the Lambs— further emphasizes that this text is produced out of the same intertextual movements that serve as the object of its narration. Like the crystal-to-be of a supersaturated solution awaiting a stimulus, “Autogenic Dreaming” was always already latent in its source texts, Tobi implies, simply waiting to be gathered together in a process of creative individuation. Human creativity thus always extends outside the human to the nonhuman points of inspiration and reference employed in acts of creation, and Autogenic Dreaming invites its reader to attend to their own transhuman collaborations.